This document presents a smart monitoring technique for solar cell systems utilizing IoT, specifically an embedded system based on the NodeMCU ESP8266 microcontroller. The study involves monitoring solar irradiance, temperature, and humidity in three regions of Egypt—Luxor, Cairo, and El-Beheira—demonstrating the system's reliability and efficiency through live data visualization via the Ubidots platform. The results suggest Luxor and Cairo are optimal locations for solar energy systems, while also highlighting the system's cost-effectiveness and real-time monitoring capabilities.

![International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE) Vol. 14, No. 2, April 2024, pp. 2322~2329 ISSN: 2088-8708, DOI: 10.11591/ijece.v14i2.pp2322-2329 2322 Journal homepage: http://ijece.iaescore.com Smart monitoring technique for solar cell systems using internet of things based on NodeMCU ESP8266 microcontroller Ahmed H. Ali1 , Raafat A. El-Kammar2 , Hesham F. Ali Hamed1,3 , Adel A. Elbaset4 , Aya Hossam2 1 Department of Telecommunications Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Egyptian Russian University, Cairo, Egypt 2 Electrical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering (Shoubra), Benha University, Benha, Egypt 3 Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Minia University, Minia, Egypt 4 Department of Electromechanics Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Heliopolis University, Cairo, Egypt Article Info ABSTRACT Article history: Received Sep 29, 2023 Revised Dec 20, 2023 Accepted Dec 26, 2023 Rapidly and remotely monitoring and receiving the solar cell systems status parameters, solar irradiance, temperature, and humidity, are critical issues in enhancement their efficiency. Hence, in the present article an improved smart prototype of internet of things (IoT) technique based on embedded system through NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E) was carried out experimentally. Three different regions at Egypt; Luxor, Cairo, and El-Beheira cities were chosen to study their solar irradiance profile, temperature, and humidity by the proposed IoT system. The monitoring data of solar irradiance, temperature, and humidity were live visualized directly by Ubidots through hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP) protocol. The measured solar power radiation in Luxor, Cairo, and El-Beheira ranged between 216-1000, 245-958, and 187-692 W/m2 respectively during the solar day. The accuracy and rapidity of obtaining monitoring results using the proposed IoT system made it a strong candidate for application in monitoring solar cell systems. On the other hand, the obtained solar power radiation results of the three considered regions strongly candidate Luxor and Cairo as suitable places to build up a solar cells system station rather than El-Beheira. Keywords: Internet of things NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E) Smart operating system Solar cell systems Solar profile This is an open access article under the CC BY-SA license. Corresponding Author: Ahmed H. Ali Department of Telecommunication Engineering, Egyptian Russian University Badr City, Cairo-Suez Road, Postal Code 11829, Egypt Email: ahmed_hamdy0064@yahoo.com 1. INTRODUCTION Enriching the industrial revolution without harming the environment, especially with the increasing climate changes, requires increased reliance on clean sources of electrical energy. Solar cell systems are one of the sustainable and green energy sources, the demand for which is increasing day by day [1]–[3]. Solar cell systems face many challenges, starting from the materials to manufacture the cells themselves to the rapid monitoring of the environmental conditions surrounding the installed solar cell systems, such as shading, temperature, and humidity. Monitoring these variables and receiving their results quickly and accurately accelerates taking appropriate procedures to repair any defect in solar systems during operation. In solar cell systems, the accuracy of measuring the solar power radiation, humidity, and temperature change and receiving is the backbone of harvesting the maximum output from it [4]–[6]. Internet of things (IoT) is one of the most efficient modern tools that proposed to monitor the solar cell systems [7]–[11]. IoT works effectively to connect physical gadgets quickly and easily to the cloud, which in turn works on exchanging the data freely that is facilitating getting the results and interacting with the gadgets via the Internet. The IoT has enhanced the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/v10734379ijecedbd-240514065030-42f11577/75/Smart-monitoring-technique-for-solar-cell-systems-using-internet-of-things-based-on-NodeMCU-ESP8266-microcontroller-1-2048.jpg)

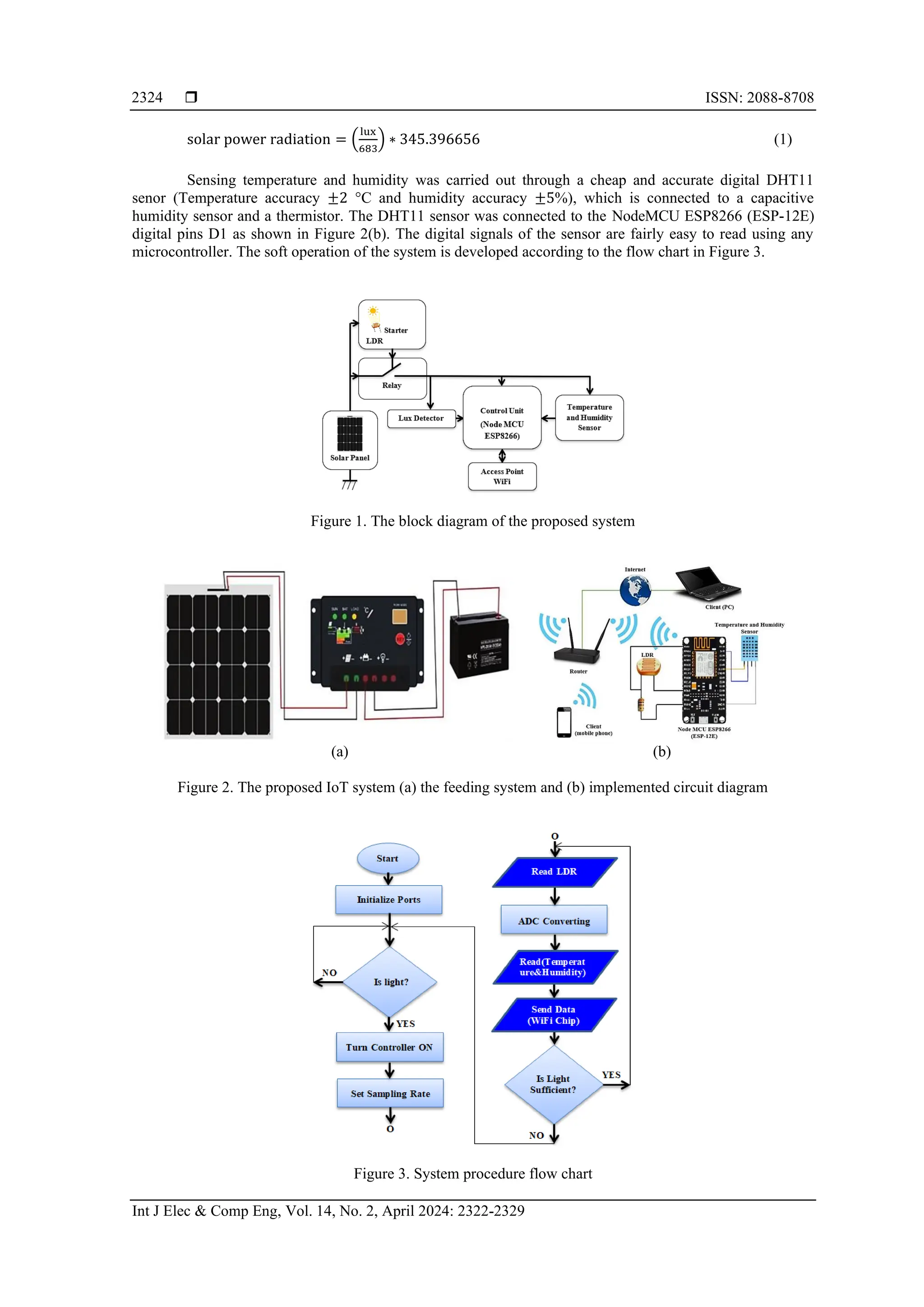

![Int J Elec & Comp Eng ISSN: 2088-8708 Smart monitoring technique for solar cell systems using internet of things based on … (Ahmed H. Ali) 2323 development of solar systems modeling and control, and the effectiveness of data prediction and acquisition [7]–[13]. The Internet of Things facilitates and accelerates data acquisition from embedded systems for analysis and speeds remote of devices associated with those systems with minimal human involvement [14], [15]. Choosing the appropriate and low-cost embedded systems strongly supports the performance of IoT systems. NodeMCU is one of the most popular embedded systems that support IoT systems in monitoring solar cell systems. Since solar cells are very sensitive to environmental changes, such as shadow, humidity, and temperature, which directly reduce the output power of solar cell systems, the monitoring and tracking systems of solar cell systems parameters are constantly used to evaluate the status of solar power plants. Monitoring systems for tracking solar cell parameters, which are constantly being developed, require further studies as they are still complex and have a high production cost, especially in small and medium-scale solar cell plants. Also, the advantage of providing a system with the ability to store the measured solar cell parameters to compare changes is an important requirement in monitoring systems [16]. In 2020, Cheddadi [17] implemented a low cost and open-source internet of things solution for real-time monitoring of environmental conditions of solar power stations. Their proposed system provides an alert for remote users for monitoring any deviation in solar power generation. Dong et al. [18] implemented in 2021 an embedded system based on IoT and neural network processing to collect the real-time video image of the solar cell system and detect the defects of solar panels in real-time. They found that their embedded system improves the performance of solar photovoltaic cell systems and reduces operation and maintenance costs. They found that the accuracy rate of their implemented design was 93.75%. In 2022, Andal and Jayapal [19] implemented a low-cost IoT controller for remotely monitoring power generated and consumed by PV/wind/battery. They used multi-function sensors to monitor the generated power and transmitted the data to various servers in the cloud via an internet connection. The authors used solar and wind energy to construct a prototype, with an Arduino microcontroller regulating and directing power transmission between slave nodes to guarantee a successful outcome. The authors recommend their proposed IoT smart communication system as a helpful technique for providing real-time monitoring and control of smart microgrids. In 2023, Hamied et al. [20] constructed a low-cost monitoring system based on IoT for an off-grid photovoltaic (PV) system. The authors created a web page to visualize the measured data. The total cost of the built system was 73 euros and consumed 13.5 Wh daily. Hence and herein, a cheap and simple IoT technique was used to monitor remotely the solar system. A NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E) system was used to measure the PV status parameters; solar irradiance, temperature, and humidity and the obtained data were sent by a proposed system based IoT techniques. To save energy and reduce maintenance costs, the proposed monitoring system was built and programmed to work smartly with sunlight. The built system also had the advantage of storing measured parameters in the event of any loss in receiving the data to ensure that none of them were lost. The rest of the paper is categorized as follows: Section 2 explains the experimental procedures and the implemented system; Section 3 explains the results and discusses them in detail; and finally, the article in its last section presented the obtained conclusions. 2. METHOD A cheap and simple smart IoT system was implemented for monitoring and sending the solar cell system status parameters; solar irradiance, temperature, and humidity. An embedded system based on NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E) integrated with different sensors was used to monitor and sense the PV status parameters, as shown in Figure 1. The sensed data was sent through ESP8266 (ESP-12E) linked by router. Additionally, the monitoring data was live displayed on the Ubidots platform, which is characterized by accessed remotely and in real-time via any device, such as laptops, PCs, and smartphones. Finally, the proposed system works as a smart system that starts running with sunrise and ends with sunset. First, the whole monitoring system was fed through 12-volt feed system contains a solar panel, charger controller, and a PV battery, as shown in Figure 2(a). NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E) is used as an open-source firmware to build IoT-based systems. NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E) is distinguished from its counterparts because ESP8266 (ESP-12E) Wi-Fi is built-in and does not need to be added as an external component. It is also characterized by its low cost and power consumption and can be simply programmed. The NodeMCU was programmed to accurately analyze the incoming solar irradiance, temperature, and humidity signals and send them via ESP8266 (ESP-12E) Wi-Fi. The ESP8266 (ESP-12E) Wi-Fi module is a system-on-a-chip (SoC) integrates with TCP/IP protocol stack giving the microcontroller access to the Wi-Fi network. The ESP8266 (ESP-12E) is capable to be either a host application (webserver) or a Wi-Fi client, which connects to local or online servers. Here, it was used as a Wi-Fi client. The used light dependent resistor (LDR) was connected to NodeMCU ESP8266 analog pins A0 to act as the input for the system, as shown in Figure 2(b). LDR was connected with fixed resistance and then connected to the NodeMCU ESP8266 to read solar power radiation according to (1) [21].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/v10734379ijecedbd-240514065030-42f11577/75/Smart-monitoring-technique-for-solar-cell-systems-using-internet-of-things-based-on-NodeMCU-ESP8266-microcontroller-2-2048.jpg)

![Int J Elec & Comp Eng ISSN: 2088-8708 Smart monitoring technique for solar cell systems using internet of things based on … (Ahmed H. Ali) 2325 According to Figure 3, the constructed system begins to search for sufficient sunlight (≥60 lux) through the LDR starter, repeating the research (is light?) until sufficient light is achieved for operation. The LDR starter ordered the relay to start the feeding of the microcontrollers and sensors (turn the controller on) from the PV system. The sampling rate, which refers to the measuring time rate is adjusted on the code (set sampling rate). Then, radiation and temperature and humidity sensors start recording the PV status parameters (irradiance, temperature, and humidity) and sending the data via Wi-Fi to the Ubidots platform. The system continues to repeat the measuring and sending the data until there is not enough light to operate (is light sufficient? <60 lux). The Arduino integrated development environment (Arduino IDE) is used to write and upload the computer code to the physical board (NodeMCU). USB driver CP2102 was used to connect between the NodeMCU board and computer. A router was used to receive the obtained data from the NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E) and send it through an IP address. An account was created on Ubidots via the HTTP protocol for facilitating the rapidly receiving and displaying the results. The library of HTTP Ubidots ESP8266 (ESP-12E) was installed on Arduino IDE. The obtained Token ID from Ubidots is fed into the code to support the results display authority. The practical implemented system, which consist of a solar panel, charger controller, a PV battery, LM7805CT regulator, smart operating system, NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E), the sensors, is shown in Figure 4. The LM7805CT regulator connected with capacitors for smoothing and two diodes for polarity and regulator protection. The smart operating system consists of a photo resistor accompanied with 5 V relay driven by BC547BP transistor for a day/system operation starter. The smart operating system automatically controls of the input power of the monitoring system depending on solar irradiance through the relay. In the experimental implemented design, the PV battery output is connected to the regulator, which in turn is connected to the smart operating system and the NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E). The radiation sensor feeds from NodeMCU, while temperature and humidity sensor were fed from the output of smart operating system to avoid its effect on the system performance. In the same respect, in order to avoid the outage in data transfer through the router, the router fed directly through the PV battery. (a) (b) Figure 4. The implemented IoT prototype (a) the installed PV panel, LDR starter, temperature and humidity sensor, and solar irradiance sensor and (b) the practical control system 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION For examining the proposed IoT system reliability and carrying out a local surveying study on the most suitable locations for installing solar cell power stations, three different solar irradiance regions were selected; Luxor with high solar copious, El-Beheira with coastal weather, and Cairo with moderate weather [22], [23]. The measured results were received using IoT system based on NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E) through the common HTTP protocol. Figure 5 shows the live results of solar power radiation, temperature, and humidity that were measured during a solar day (6 am to 7 pm) and transmitted using the proposed IoT system. The received results of solar power radiation, temperature, and humidity are displayed in Figure 6. It is clearly observed that the solar power irradiance of Luxor is the highest followed by Cairo then El-Beheira, as shown in Figures 6(a). Luxor is the clearest sky, has the most minor dust, and is the equator nearest city compared to Cairo and El-Beheira. On the other hand, Luxor city has almost no industrial factories, which directly affects the solar profile through the environmental pollution. The lowest solar profile of El-Beheira is due to being a coastal city with variable weather and is usually cloudy. Although Cairo weather is close to Luxor, the spread out of the factories in and around it affects the solar irradiance profile. The received temperature and humidity using the proposed IoT system are shown in Figure 6(b) and (c). It is noticeable that the behavior of both temperature and humidity is completely harmonious with the behavior of solar](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/v10734379ijecedbd-240514065030-42f11577/75/Smart-monitoring-technique-for-solar-cell-systems-using-internet-of-things-based-on-NodeMCU-ESP8266-microcontroller-4-2048.jpg)

![ ISSN: 2088-8708 Int J Elec & Comp Eng, Vol. 14, No. 2, April 2024: 2322-2329 2326 power radiation. Humidity is a powerful factor affecting the performance of solar cells, through its direct effect on solar power, in addition to the formation of a thin layer of water vapor on the surface of the cell [15], [17], [19]. Hence, the low value of moisture in Luxor reflects positively on the performance of the solar cells and hence the increase in their output power in contrast to the El-Beheira. Figure 5. The obtained solar power radiation, temperature, humidity result of the proposed using IoT system (a) (b) (c) Figure 6. Measured (a) solar power radiation, (b) temperature, and (c) humidity in the studied regions 0 400 800 1200 5 8 11 14 17 20 Solar Power Radiation (W/m 2 ) Time (Hour) Luxor Cairo 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 5 8 11 14 17 20 Temperature (°C) Time (Hour) Luxor Cairo 20 40 60 80 100 5 8 11 14 17 20 Humidity (%) Time (Hour) Luxor Cairo El-Beheira](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/v10734379ijecedbd-240514065030-42f11577/75/Smart-monitoring-technique-for-solar-cell-systems-using-internet-of-things-based-on-NodeMCU-ESP8266-microcontroller-5-2048.jpg)

![Int J Elec & Comp Eng ISSN: 2088-8708 Smart monitoring technique for solar cell systems using internet of things based on … (Ahmed H. Ali) 2327 Finally, to assess the efficiency of the proposed smart IoT system in monitoring the parameters of the PV status and its economic feasibility, the implemented system was characterized by the advantages: i) cost-effective and easy to maintain; ii) low-consumed power and feeds directly from the PV system; iii) measuring the solar irradiance, temperature, and humidity simultaneously; and iv) displaying the measured data in live profiles (curves and tables) on a webpage, making it easy to access the data at any time remotely. However, the system has two limitations, which are i) the limit of the distance of the Wi-Fi module and ii) the security of measured data. On the other hand, the reliance of the implemented strategy in the proposed system on NodeMCU ESP8266(ESP-12E) distinguishes it from its peers, which depend on Arduino [24], [25] (Uno, Nano, Mega), field-programmable gate array (FPGA) [26], [27], and Raspberry Pi [28]–[30] in its low cost, ease of programming, and availability. Table 1 summarizes the comparison between available previously designed IoT-based systems for monitoring the PV systems in the 2018-2023 period and the implemented IoT system in our article. The carried-out comparison focused on the available data of the used microcontroller, transceiver, cost, and the monitoring parameters. Finally, according to the listed comparison in Table 1, the proposed IoT monitoring system in our work is considered the lowest cost, in addition to the simplicity of its components. Additionally, it has a built-in Wi-Fi module, which makes it less energy- consuming and gives it several advantages over its peers. Table 1. A comparison between the implemented smart IoT system and the available previously designed IoT-based systems Year [Ref.] Controller Cost (€) Monitored parameters Board Built-in Wi-Fi? Wi-Fi Transceiver 2018 [30] Arduino Uno No Wireless: Ethernet 300.71 PV current & voltage, solar irradiance, temperature, and others 2019 [31] Raspberry PI Yes LoRa 39.26 Solar irradiance, temperature, and PV current, voltage, & power 2020 [32] Arduino Mega No Wireless: ESP8266 63.04 Solar irradiance, temperature, duty cycle, and PV current, voltage, & power 2022 [33] Arduino Nano No LoRa 18.72 Solar irradiance, temperature, and PV current & voltage 2023 [34] Arduino Mega No NodeMCU ESP8266 ـــ Light intensity, temperature, and PV current & voltage Our work NodeMCU Yes ESP8266(ESP-12E) 8.65 Solar irradiance, temperature, humidity 4. CONCLUSION An extensive study was conducted on a developed IoT system based on an embedded system using NodeMCU ESP8266 (ESP-12E) in order to monitor solar cell systems and the rapid of receiving the results of solar power radiation, temperature, and humidity. The proposed system is characterized by its simplicity and low cost, consisting of an integrated control board, NodeMCU, and Wi-Fi module ESP8266 (ESP-12E) as a built-in unit. The proposed system succeeded in displaying a live profile of all the parameters of the installed solar cell system; solar power radiation, temperature, and humidity. Hence, the considered system is a strong candidate for use in the continuous monitoring of solar cell systems aiming to quickly intervene to solve any problems encountering operation, which is reflected positively on improving the solar system's performance. On the other hand, and based on the survey results of the solar irradiance profile, Luxor and Cairo cities are strongly candidated as suitable locations for solar power station installation. REFERENCES [1] M. Abdelsattar, A. M. A. El Hamed, A. A. Elbaset, S. Kamel, and M. Ebeed, “Optimal integration of photovoltaic and shunt compensator considering irradiance and load changes,” Computers and Electrical Engineering, vol. 97, Art. no. 107658, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107658. [2] S. A. Mohamed Abdelwahab, A. A. Elbaset, F. Yousef, and W. S. E. Abdellatif, “Performance enhancement of PV grid connected systems with different fault conditions,” International Journal on Electrical Engineering and Informatics, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 873–897, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.15676/ijeei.2021.13.4.8. [3] A. P. Yoganandini and G. S. Anitha, “A modified particle swarm optimization algorithm to enhance MPPT in the PV array,” International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 5001–5008, Oct. 2020, doi: 10.11591/IJECE.V10I5.PP5001-5008. [4] S. Shapsough, M. Takrouri, R. Dhaouadi, and I. Zualkernan, “An IoT-based remote IV tracing system for analysis of city-wide solar power facilities,” Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 57, Art. no. 102041, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102041. [5] K. L. Shenoy, C. G. Nayak, and R. P. Mandi, “Effect of partial shading in grid connected solar PV system with FL controller,” International Journal of Power Electronics and Drive Systems (IJPEDS), vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 431–440, Mar. 2021, doi: 10.11591/ijpeds.v12.i1.pp431-440. [6] G. Boubakr, F. Gu, L. Farhan, and A. Ball, “Enhancing virtual real-time monitoring of photovoltaic power systems based on the internet of things,” Electronics (Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 15, p. 2469, Aug. 2022, doi: 10.3390/electronics11152469.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/v10734379ijecedbd-240514065030-42f11577/75/Smart-monitoring-technique-for-solar-cell-systems-using-internet-of-things-based-on-NodeMCU-ESP8266-microcontroller-6-2048.jpg)

![ ISSN: 2088-8708 Int J Elec & Comp Eng, Vol. 14, No. 2, April 2024: 2322-2329 2328 [7] F. Peprah, S. Gyamfi, M. Amo-Boateng, E. Buadi, and M. Obeng, “Design and construction of smart solar powered egg incubator based on GSM/IoT,” Scientific African, vol. 17, p. e01326, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2022.e01326. [8] K. H. Tseng, M. Y. Chung, L. H. Chen, and L. A. Chou, “A study of green roof and impact on the temperature of buildings using integrated IoT system,” Scientific Reports, vol. 12, no. 1, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-20552-6. [9] K. Kommuri and V. R. Kolluru, “Implementation of modular MPPT algorithm for energy harvesting embedded and IoT applications,” International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 3660–3670, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.11591/ijece.v11i5.pp3660-3670. [10] K. Luechaphonthara and A. Vijayalakshmi, “IoT based application for monitoring electricity power consumption in home appliances,” International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 4988–4992, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.11591/ijece.v9i6.pp4988-4992. [11] Z. Kaleem, U. Mehmood, Zain-Ul-Abidin, R. Nazar, and Y. Qayyum Gill, “Synthesis of polymer-gel electrolytes for quasi solid- state dye-sensitized solar cells and Modules: A potential photovoltaic technology for powering internet of things (IoTs) applications,” Materials Letters, vol. 319, p. 132270, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2022.132270. [12] M. Yakut and N. B. Erturk, “An IoT-based approach for optimal relative positioning of solar panel arrays during backtracking,” Computer Standards and Interfaces, vol. 80, p. 103568, Mar. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.csi.2021.103568. [13] F. F. Ahmad, C. Ghenai, and M. Bettayeb, “Maximum power point tracking and photovoltaic energy harvesting for Internet of Things: A comprehensive review,” Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, vol. 47, Art. no. 101430, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.seta.2021.101430. [14] A. Aslam et al., “Dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) as a potential photovoltaic technology for the self-powered internet of things (IoTs) applications,” Solar Energy, vol. 207, pp. 874–892, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2020.07.029. [15] N. Chamara, M. D. Islam, G. (Frank) Bai, Y. Shi, and Y. Ge, “Ag-IoT for crop and environment monitoring: Past, present, and future,” Agricultural Systems, vol. 203, Art. no. 103497, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2022.103497. [16] J. Huaman Castañeda, P. C. Tamara Perez, E. Paiva-Peredo, and G. Zarate-Segura, “Design of a prototype for sending fire notifications in homes using fuzzy logic and internet of things,” International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), vol. 14, no. 1, p. 248, Feb. 2024, doi: 10.11591/ijece.v14i1.pp248-257. [17] Y. Cheddadi, H. Cheddadi, F. Cheddadi, F. Errahimi, and N. Es-sbai, “Design and implementation of an intelligent low-cost IoT solution for energy monitoring of photovoltaic stations,” SN Applied Sciences, vol. 2, no. 7, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1007/s42452-020- 2997-4. [18] M. Dong, J. Zhao, D. A. Li, B. Zhu, S. An, and Z. Liu, “ISEE: Industrial internet of things perception in solar cell detection based on edge computing,” International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, vol. 17, no. 11, p. 155014772110505, Nov. 2021, doi: 10.1177/15501477211050552. [19] C. K. Andal and R. Jayapal, “Design and implementation of IoT based intelligent energy management controller for PV/wind/battery system with cost minimization,” Renewable Energy Focus, vol. 43, pp. 255–262, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.ref.2022.10.004. [20] A. Hamied, A. Mellit, M. Benghanem, and S. Boubaker, “IoT-based low-cost photovoltaic monitoring for a greenhouse farm in an arid region,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 9, p. 3860, Apr. 2023, doi: 10.3390/en16093860. [21] C. Carvalho and N. Paulino, “On the feasibility of indoor light energy harvesting for wireless sensor networks,” Procedia Technology, vol. 17, pp. 343–350, 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.protcy.2014.10.206. [22] H. El-Askary, P. Kosmopoulos, and S. Kazadzis, “The solar atlas of Egypt,” Ministry of Electricity and Renewable Energy (Egypt), pp. 1–277, 2018. [23] A. H. Ali, A. S. Nada, and A. S. Shalaby, “Economical and efficient technique for a static localized maximum sun lux determination,” International Journal of Power Electronics and Drive Systems (IJPEDS), vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 777–784, Jun. 2019, doi: 10.11591/ijpeds.v10.i2.pp777-784. [24] D. D. Prasanna Rani, D. Suresh, P. Rao Kapula, C. H. Mohammad Akram, N. Hemalatha, and P. Kumar Soni, “IoT based smart solar energy monitoring systems,” Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 80, pp. 3540–3545, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.07.293. [25] O. V. G. Swathika and K. T. M. U. Hemapala, “IoT based energy management system for standalone PV systems,” Journal of Electrical Engineering and Technology, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 1811–1821, Jun. 2019, doi: 10.1007/s42835-019-00193-y. [26] A. S. Alqahtani, A. Mubarakali, P. Parthasarathy, G. Mahendran, and U. A. Kumar, “Solar PV fed brushless drive with optical encoder for agriculture applications using IoT and FPGA,” Optical and Quantum Electronics, vol. 54, no. 11, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s11082-022-04065-0. [27] A. Mellit, H. Rezzouk, A. Messai, and B. Medjahed, “FPGA-based real time implementation of MPPT-controller for photovoltaic systems,” Renewable Energy, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 1652–1661, May 2011, doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2010.11.019. [28] P. T. Le, H. L. Tsai, and P. L. Le, “Development and performance evaluation of photovoltaic (PV) evaluation and fault detection system using hardware-in-the-loop simulation for PV applications,” Micromachines, vol. 14, no. 3, Art. no. 674, Mar. 2023, doi: 10.3390/mi14030674. [29] M. D. Mudaliar and N. Sivakumar, “IoT based real time energy monitoring system using Raspberry Pi,” Internet of Things (Netherlands), vol. 12, p. 100292, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.iot.2020.100292. [30] A. Lopez-Vargas, M. Fuentes, and M. Vivar, “IoT application for real-time monitoring of solar home systems based on Arduinotm with 3G connectivity,” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 679–691, Jan. 2019, doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2018.2876635. [31] J. M. Paredes-Parra, A. J. García-Sánchez, A. Mateo-Aroca, and Á. Molina-García, “An alternative internet-of-things solution based on LOra for PV power plants: Data monitoring and management,” Energies, vol. 12, no. 5, Art. no. 881, Mar. 2019, doi: 10.3390/en12050881. [32] N. Rouibah, L. Barazane, M. Benghanem, and A. Mellit, “IoT-based low-cost prototype for online monitoring of maximum output power of domestic photovoltaic systems,” ETRI Journal, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 459–470, Apr. 2021, doi: 10.4218/etrij.2019- 0537. [33] M. Ş. Kalay, B. Kılıç, A. Mellit, B. Oral, and Ş. Sağlam, “IoT-based data acquisition and remote monitoring system for large- scale photovoltaic power plants,” in Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, vol. 954, Springer Nature Singapore, 2023, pp. 631–639. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-6223-3_65. [34] M. Ul Mehmood et al., “A new cloud-based IoT solution for soiling ratio measurement of PV systems using artificial neural network,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 2, p. 996, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.3390/en16020996.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/v10734379ijecedbd-240514065030-42f11577/75/Smart-monitoring-technique-for-solar-cell-systems-using-internet-of-things-based-on-NodeMCU-ESP8266-microcontroller-7-2048.jpg)