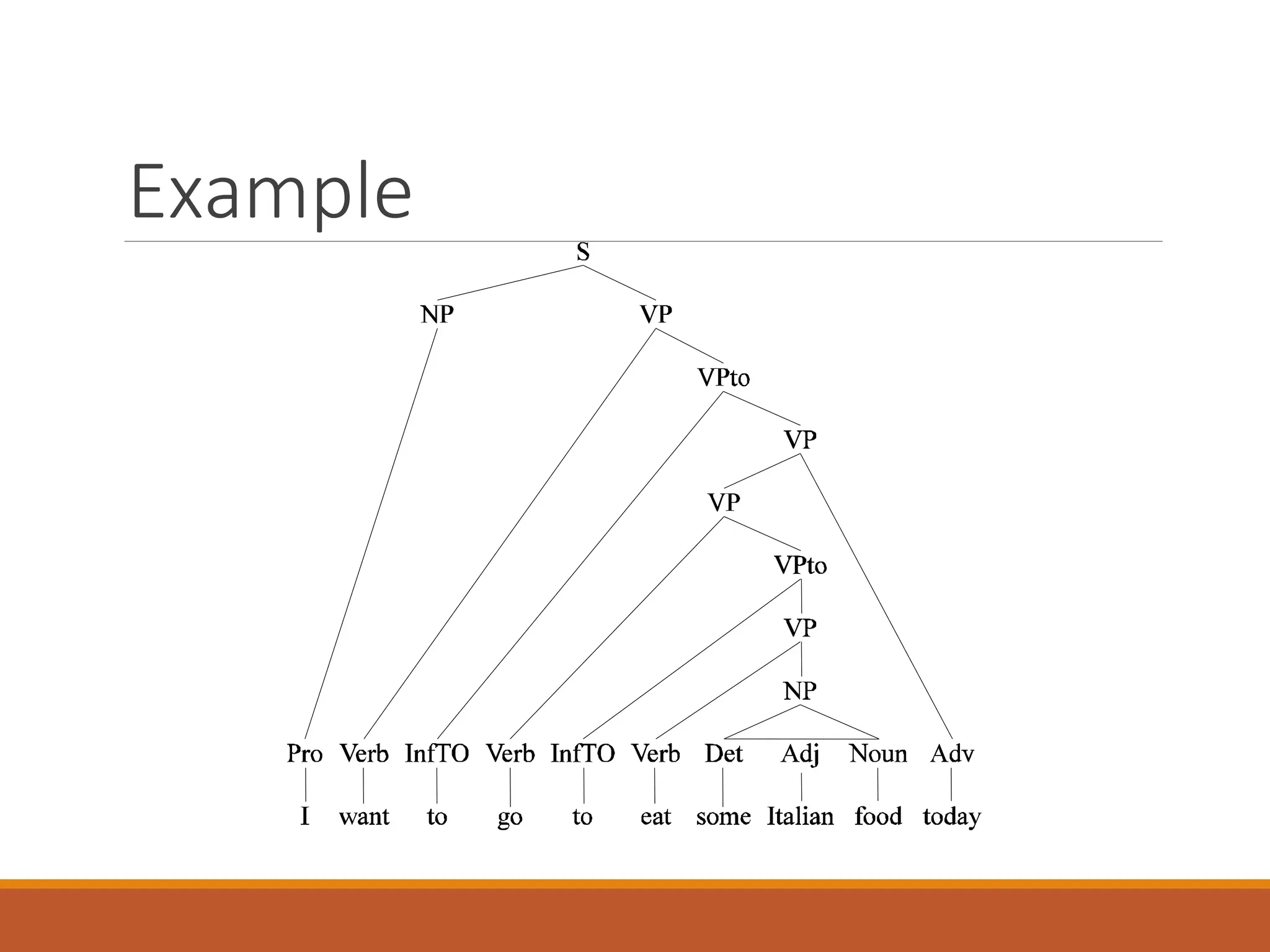

Dr. Sohaib Latif discusses semantic analysis within natural language processing, emphasizing the importance of syntax and the principle of compositionality. He outlines general mappings from syntactic parse trees to semantic representations and highlights challenges such as ambiguity and non-compositionality in semantic interpretation. The document also touches on the development of semantic grammars and their use in conversational agents.