Compositional Semantics An Introduction To The Syntaxsemantics Interface Pauline Jacobson Compositional Semantics An Introduction To The Syntaxsemantics Interface Pauline Jacobson Compositional Semantics An Introduction To The Syntaxsemantics Interface Pauline Jacobson

![(18) a. Bettyj is [NP the wifei of herj childhood sweetheart]. b. Betty, y [y = the x: x is a woman and x is married to y’s childhood sweetheart] Since we are asserting identity between Betty and the person married to Betty’s childhood sweetheart, it of course follows that Betty is married to Betty’s childhood sweetheart and so the full sentence (16) will end up with the relevant meaning.9 But the claim that the object NP itself (the wife of her childhood sweetheart) does have the meaning represented in (12) is not threatened. The same point holds for (17), whose meaning can be represented as (19a) or (19b). (19) a. the womanj whoj is the wifei of herj childhood sweetheart b. the y: y is a woman and y = the x: x is a woman and x is married to y’s childhood sweetheart Is there a way to confirm that this is the right sort of explanation for these apparent counterexamples? Indeed there is, and it centers on the contrast between (8) and (9) which was discussed earlier. We leave it to the interested reader in the exercise to play with this and get a sense of why (8) is ambiguous and (9) is not. Having completed that, one should be able to see how it is that this gives support for the explanation offered above as to why (17) does not threaten the claim that the wife of her childhood sweetheart cannot correspond to the meaning shown informally in (12). *1.2. Work out—using the informal representations either with indices or the representations with variables—why it is that (7) is ambiguous and (8) is not. Of course you will need to think a bit about how to treat only, but nothing very complex is required. You can be perfectly informal in your treatment of only, but you should be able to get a feel for why these two differ. 9 This general observation—although for a slightly different case—was made in Postal (1970) who distinguished between “presuppposed” coreference and “asserted” coreference. Here the fact that Betty and the wife of her childhood sweetheart end up “referring” to the same individual is exactly what the sentence is asserting. 18 1. INTRODUCTION](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-43-2048.jpg)

![is true, and uses that fact to enrich their knowledge of the world). Thus (1) is true and (2) is false: (1) Barack Obama moved into the White House on Jan. 20, 2009. (2) John McCain moved into the White House on Jan. 20, 2009. Hence, one basic notion used for the construction of meanings is a truth value—for now assume that there are just two such values: true and false. (More on this directly.) The claim that truth values are a fundamental part of meaning is also motivated by noting that—as shown by the examples above—speakers have intuitions about truth, given certain facts about the world, just like they do about acceptability. And these judgments can be used to test the adequacy of particular theories of meaning. Following standard practice, we use 1 for true and 0 for false. Thus the set of truth values {1,0} and we will also refer to this set as t. Let us use [[Æ]] to mean the semantic value (i.e., the meaning) of a linguistic expression Æ. Then (temporarily) we can say that [[Barack Obama moved into the White House on Jan. 20, 2009]] = 1. Some worries should immediately spring to mind. The most obvious is that something seems amiss in calling the meaning of (1) “true” even if we are willing to accept the fact that it is true. We will enrich the toolbox directly to take care of that. But there are other objections: does it really make sense to say that all declarative sentences are true or false? Clearly not—for some sentences the truth value depends on who is speaking (and on when the sentence is spoken). Take (3): (3) I am President of the United States. This is true if spoken by Barack Obama in 2011, but not if spoken by John McCain and not true if spoken by Barack Obama in 2006. So this has no truth value in and of itself. Nonetheless once certain parameters are fixed (time of utterance and speaker) it is either true or false. So we might want to think of the meaning of (3) as a function into {1,0}—it does yield a truth value but only once we fix certain parameters. But it seems inescapable that a declarative sentence is telling us something about the world, and so truth values are certainly one fundamental piece. In fact, there are many parameters that need to be set in order to derive a truth value. Certain words like I, you, here, now, etc. quite obvi- ously have the property that their value depends on when, where, and by whom these are spoken (these are called indexicals). There are also more 2.2. TRUTH CONDITIONS 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-54-2048.jpg)

![disappeared before the Modern period; and on both continents the great Post-glacial subsidence or deluge may have swept away some of the species. Such a supposition seems necessary to account for the phenomena of the gravel and cave deposits of England, and Cope has recently suggested it in explanation of similar storehouses of fossil animals in America.[AS] [AS] Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, April 1871. Among the many pictures which this fertile subject calls up, perhaps none is more curious than that presented by the Post-glacial cavern deposits. We may close our survey of this period with the exploration of one of these strange repositories; and may select Kent’s Hole at Torquay, so carefully excavated and illumined with the magnesium light of scientific inquiry by Mr. Pengelly and a committee of the British Association. The somewhat extensive and ramifying cavern of Kent’s Hole is an irregular excavation, evidently due partly to fissures in limestone rock, and partly to the erosive action of water enlarging such fissures into chambers and galleries. At what time it was originally cut we do not know, but it must have existed as a cavern at the close of the Pliocene or beginning of the Post-pliocene period, since which time it has been receiving a series of deposits which have quite filled up some of its smaller branches. First and lowest, according to Mr. Pengelly, is a “breccia” or mass of broken and rounded stones, with hardened red clay filling the interstices. Most of the stones are of the rock which forms the roof and walls of the cave, but many, especially the rounded ones, are from more distant parts of the surrounding country. In this mass, the depth of which is unknown, are numerous bones, all of one kind of animal, the cave bear, a creature which seems to have lived in Western Europe from the close of the Pliocene down to the modern period. It must have been one of the earliest and most permanent tenants of Kent’s Hole at a time when its lower chambers were still filled with water. Next above the breccia is a floor of “stalagmite” or stony carbonate of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-57-2048.jpg)

![difficult and confused character of the deposits in this and similar caves, too much value should not be attached to such histories, which may at any time be contradicted or modified by new facts or different explanations of those already known. The time involved depends very much, as already stated, on the question whether we regard the Post- glacial subsidence and re-elevation as somewhat sudden, or as occupying long ages at the slow rate at which some parts of our continents are now rising or sinking.[AT] [AT] Another element in this is also the question raised by Dawkins, Geikie, and others as to subdivisions of the Post-glacial period and intermissions of the Glacial cold. After careful consideration of these views, however, I cannot consider them as of much importance. Such are the glimpses, obscure though stimulating to the imagination, which geology can give of the circumstances attending the appearance of man in Western Europe. How far we are from being able to account for his origin, or to give its circumstances and relative dates for the whole world, the reader will readily understand. Still it is something to know that there is an intelligible meeting-place of the later geological ages and the age of man, and that it is one inviting to many and hopeful researches. It is curious also to find that the few monuments disinterred by geology, the antediluvian record of Holy Scripture, and the golden age of heathen tradition, seem alike to point to similar physical conditions, and to that simple state of the arts of life in which “gold and wampum and flint stones”[AU] constituted the chief material treasures of the earliest tribes of men. They also point to the immeasurable elevation, then as now, of man over his brute rivals for the dominion of the earth. To the naturalist this subject opens up most inviting yet most difficult paths of research, to be entered on with caution and reverence, rather than in the bold and dashing spirit of many modern attempts. The Christian, on his part, may feel satisfied that the scattered monumental relics of the caves and gravels will tell no story very different from that which he has long believed on other evidence, nor anything inconsistent with those views of man’s heavenly origin and destiny which have been the most precious inheritance of the greatest and best minds of every age, from that early pre-historic](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-61-2048.jpg)

![period when men, “palaeolithic” men, no doubt, began to “invoke the name of Jehovah,” the coming Saviour, down to those times when life and immortality are brought to light, for all who will see, by the Saviour already come. [AU] So I read the “gold, bedolah, and shoham” of the description of Eden in Genesis ii.—the oldest literary record of the stone age. In completing this series of pictures, I wish emphatically to insist on the imperfection of the sketches which I have been able to present, and which are less, in comparison with the grand march of the creative work, even as now imperfectly known to science, than the roughest pencilling of a child when compared with a finished picture. If they have any popular value, it will be in presenting such a broad general view of a great subject as may induce further study to fill up the details. If they have any scientific value, it will be in removing the minds of British students for a little from the too exclusive study of their own limited marginal area, which has been to them too much the “celestial empire” around which all other countries must be arranged, and in divesting the subject of the special colouring given to it by certain prominent cliques and parties. Geology as a science is at present in a peculiar and somewhat exceptional state. Under the influence of a few men of commanding genius belonging to the generation now passing away, it has made so gigantic conquests that its armies have broken up into bands of specialists, little better than scientific banditti, liable to be beaten in detail, and prone to commit outrages on common sense and good taste, which bring their otherwise good cause into disrepute. The leaders of these bands are, many of them, good soldiers, but few of them fitted to be general officers, and none of them able to reunite our scattered detachments. We need larger minds, of broader culture and wider sympathies, to organise and rule the lands which we have subdued, and to lead on to further conquests. In the present state of natural science in Britain, this evil is perhaps to be remedied only by providing a wider and deeper culture for our young men. Few of our present workers have enjoyed that thorough](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-62-2048.jpg)

![species, which have sprung from these discussions, and the harvest of which will be reaped by the true naturalists of the future. Thus these theories as to the origin of men and animals and plants are full of present significance, and may be studied with profit by all; and in no part of their applications more usefully than in that which relates to man. Let us then inquire,—1. What is implied in the idea of evolution as applied to man? 2. What is implied in the idea of creation? 3. How these several views accord with what we actually know as the result of scientific investigation? The first and second of these questions may well occupy the whole of this chapter, and we shall be able merely to glance at their leading aspects. In doing so, it may be well first to place before us in general terms the several alternatives which evolutionists offer, as to the mode in which the honour of an origin from apes or ape-like animals can be granted to us, along with the opposite view as to the independent origin of man which have been maintained either on scientific or scriptural grounds. All the evolutionist theories of the origin of man depend primarily on the possibility of his having been produced from some of the animals more closely allied to him, by the causes now in operation which lead to varietal forms, or by similar causes which have been in operation; and some attach more and others less weight to certain of these causes, or gratuitously suppose others not actually known. Of such causes of change some are internal and others external to the organism. With respect to the former, one school assumes an innate tendency in every species to change in the course of time.[AV] Another believes in exceptional births, either in the course of ordinary generation or by the mode of parthenogenesis.[AW] Another refers to the known facts of reproductive accelleration or retardation observed in some humble creatures.[AX] New forms arising in any of these ways or fortuitously, may, it is supposed, be perpetuated and increased and further improved by favouring external circumstances and the effort of the organism to avail itself of these,[AY] or by the struggle for existence and the survival of the fittest.[AZ] [AV] Parsons, Owen.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-67-2048.jpg)

![[AW] Mivart, Ferris. [AX] Hyatt and Cope. [AY] Lamarck, etc. [AZ] Darwin, etc. On the other hand, those who believe in the independent origin of man admit the above causes as adequate only to produce mere varieties, liable to return into the original stock. They may either hold that man has appeared as a product of special and miraculous creation, or that he has been created mediately by the operation of forces also concerned in the production of other animals, but the precise nature of which is still unknown to us; or lastly, they may hold what seems to be the view favoured by the book of Genesis, that his bodily form is a product of mediate creation and his spiritual nature a direct emanation from his Creator. The discussion of all these rival theories would occupy volumes, and to follow them into details would require investigations which have already bewildered many minds of some scientific culture. Further, it is the belief of the writer that this plunging into multitudes of details has been fruitful of error, and that it will be a better course to endeavour to reach the root of the matter by looking at the foundations of the general doctrine of evolution itself, and then contrasting it with its rival. Taking, then, this broad view of the subject, two great leading alternatives are presented to us. Either man is an independent product of the will of a Higher Intelligence, acting directly or through the laws and materials of his own institution and production, or he has been produced by an unconscious evolution from lower things. It is true that many evolutionists, either unwilling to offend, or not perceiving the logical consequences of their own hypothesis, endeavour to steer a middle course, and to maintain that the Creator has proceeded by way of evolution. But the bare, hard logic of Spencer, the greatest English authority on evolution, leaves no place for this compromise, and shows that the theory, carried out to its legitimate consequences, excludes the knowledge of a Creator and the possibility of His work. We have, therefore, to choose between evolution and creation; bearing in mind,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-68-2048.jpg)

![life which have been supposed to show a union of the two kingdoms, disappear on investigation. This gap can, I believe, be filled up only by an appeal to our ignorance. There may be, or may have been, some simple creature unknown to us, on the extreme verge of the plant kingdom, that was capable of passing the limit and becoming an animal. But no proof of this exists. It is true that the primitive germs of many kinds of humble plants and animal s are so much alike, that much confusion has arisen in tracing their development. It is also true that some of these creatures can subsist under very dissimilar conditions, and in very diverse states, and that under the specious name of Biology,[BA] we sometimes find a mass of these confusions, inaccurate observations and varietal differences made to do duty for scientific facts. But all this does not invalidate the grand primary distinction between the animal and the plant, which should be thoroughly taught and illustrated to all young naturalists, as one of the best antidotes to the fallacies of the evolutionist school. [BA] It is doubtful whether men who deny the existence of vital force have a right to call their science “Biology,” any more than atheists have to call their doctrine “Theology;” and it is certain that the assumption of a science of Biology as distinct from Phytology and Zoology, or including both, is of the nature of a “pious fraud” on the part of the more enlightened evolutionists. The objections stated in the text, to what have been called Archebiosis and Heterogenesis seem perfectly applicable, in so far as I can judge from a friendly review by Wallace, to the mass of heterogeneous material accumulated by Dr. Bastian in his recent volumes. The conclusions of this writer, would also, if established, involve evolution in a fatal embarras des richesses, by the hourly production during all geological time, of millions of new forms all capable of indefinite development. A third is that between any species of animal or plant and any other species. It was this gap, and this only, which Darwin undertook to fill up by his great work on the origin of species, but, notwithstanding the immense amount of material thus expended, it yawns as wide as ever, since it must be admitted that no case has been ascertained in which an individual of one species has transgressed the limits between it and other species. However extensive the varieties produced by artificial breeding, the essential characters of the species remain, and even its](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-72-2048.jpg)

![The reader will now readily perceive that the simplicity and completeness of the evolutionist theory entirely disappear when we consider the unproved assumptions on which it is based, and its failure to connect with each other some of the most important facts in nature: that, in short, it is not in any true sense a philosophy, but merely an arbitrary arrangement of facts in accordance with a number of unproved hypotheses. Such philosophies, “falsely so called,” have existed ever since man began to reason on nature, and this last of them is one of the weakest and most pernicious of the whole. Let the reader take up either of Darwin’s great books, or Spencer’s “Biology,” and merely ask himself as he reads each paragraph, “What is assumed here and what is proved?” and he will find the whole fabric melt away like a vision. He will find, however, one difference between these writers. Darwin always states facts carefully and accurately, and when he comes to a difficulty tries to meet it fairly. Spencer often exaggerates or extenuates with reference to his facts, and uses the arts of the dialectician where argument fails. Many naturalists who should know better are puzzled with the great array of facts presented by evolutionists; and while their better judgment causes them to doubt as to the possibility of the structures which they study being produced by such blind and material processes, are forced to admit that there must surely be something in a theory so confidently asserted, supported by so great names, and by such an imposing array of relations which it can explain. They would be relieved from their weak concessions were they to study carefully a few of the instances adduced, and to consider how easy it is by a little ingenuity to group undoubted facts around a false theory. I could wish to present here illustrations of this, which abound in every part of the works I have referred to, but space will not permit. One or two must suffice. The first may be taken from one of the strong points often dwelt on by Spencer in his “Biology.”[BB] [BB] “Principles of Biology,” § 118. But the experiences which most clearly illustrate to us the process of general evolution are our experiences of special evolution, repeated in every plant and animal. Each organism exhibits, within a short space](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-74-2048.jpg)

![It would only weary the reader to follow evolution any further into details, especially as my object in this chapter is to show that generally, and as a theory of nature and of man, it has no good foundation; but we should not leave the subject without noting precisely the derivation of man according to this theory; and for this purpose I may quote Darwin’s summary of his conclusions on the subject.[BC] [BC] “Descent of Man,” part ii., ch. 21. “Man,” says Mr. Darwin, “is descended from a hairy quadruped, furnished with a tail and pointed ears, probably arboreal in its habits, and an inhabitant of the Old World. This creature, if its whole structure had been examined by a naturalist, would have been classed amongst the quadrumana, as surely as would the common, and still more ancient, progenitor of the Old and New World monkeys. The quadrumana and all the higher mammals are probably derived from an ancient marsupial animal; and this, through a long line of diversified forms, either from some reptile-like or some amphibian-like creature, and this again from some fish-like animal. In the dim obscurity of the past we can see that the early progenitor of all the vertebrata must have been an aquatic animal, provided with branchiæ, with the two sexes united in the same individual, and with the most important organs of the body (such as the brain and heart) imperfectly developed. This animal seems to have been more like the larvæ of our existing marine Ascidians than any other form known.” The author of this passage, in condescension to our weakness of faith, takes us no further back than to an Ascidian, or “sea-squirt,” the resemblance, however, of which to a vertebrate animal is merely analogical, and, though a very curious case of analogy, altogether temporary and belonging to the young state of the creature, without affecting its adult state or its real affinities with other mollusks. In order, however, to get the Ascidian itself, he must assume all the “conditions” already referred to in the previous part of this article, and fill most of the gaps. He has, however, in the “Origin of Species” and “Descent of Man,” attempted merely to fill one of the breaks in the evolutionary series, that between distinct species, leaving us to receive](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-79-2048.jpg)

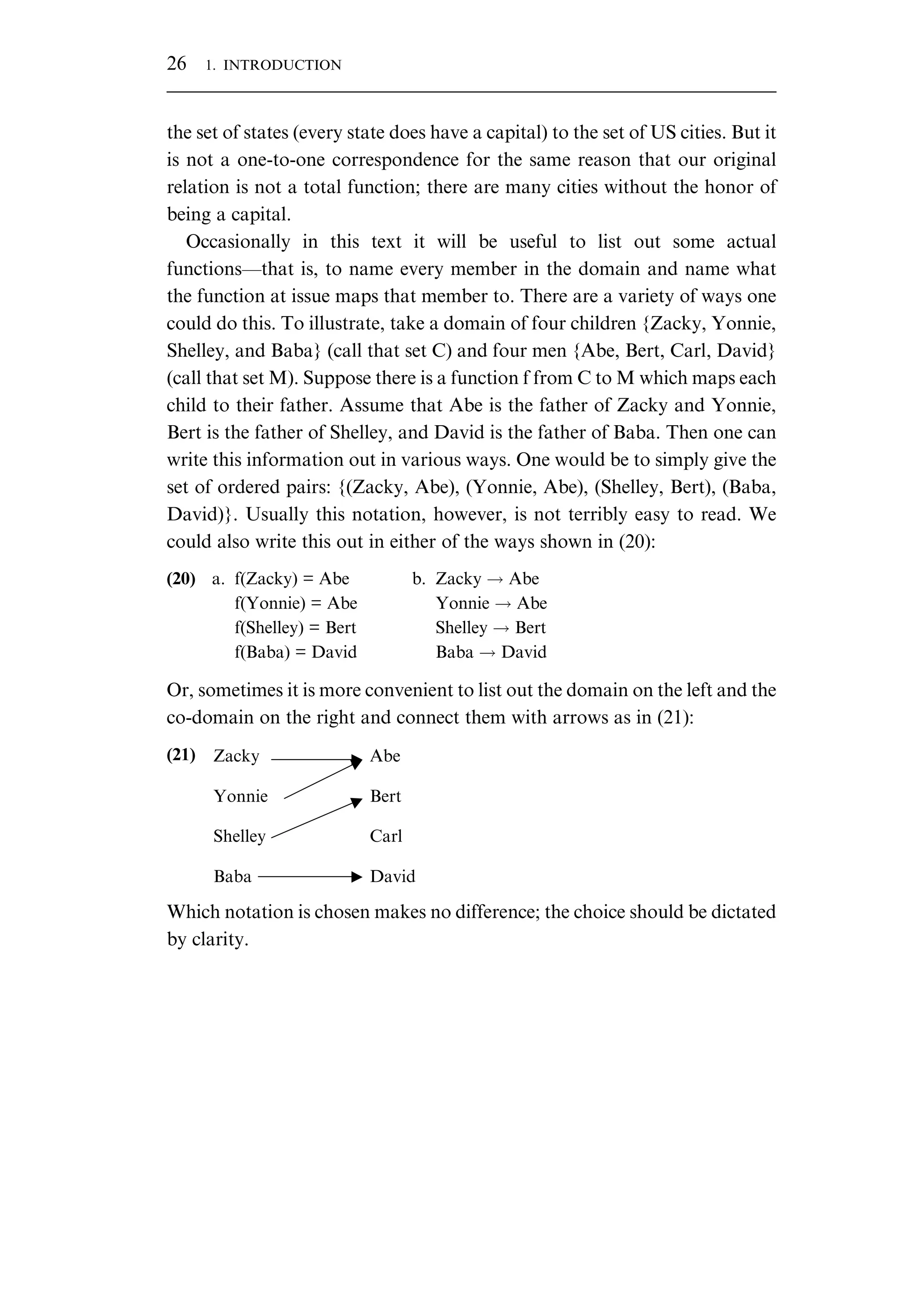

![readily imagine that they would now suppose they knew the whole truth, and might believe that any one who taught them that the engine was a product of intelligent design, was only taking them back to the old doctrine of the thirsty demon of the boiler. This is, I think, at present, the mental condition of many scientists with reference to creation. Here we come to the first demand which the doctrine of creation makes on us by way of premises. In order that there may be creation there must be a primary Self-existent Spirit, whose will is supreme. The evolutionist cannot refuse to admit this on as good ground as that on which we hesitate to receive the postulates of his faith. It is no real objection to say that a God can be known to us only partially, and, with reference to His real essence, not at all; since, even if we admit this, it is no more than can be said of matter and force. I am not about here to repeat any of the ordinary arguments for the existence of a spiritual First Cause, and Creator of all things, but it may be proper to show that this assumption is not inconsistent with experience, or with the facts and principles of modern science. The statement which I would make on this point shall be in the words of a very old writer, not so well known as he should be to many who talk volubly enough about antagonisms between science and Christianity: “That which is known of God is manifest in them (in men), for God manifested it unto them. For since the creation of the world His invisible things, even His eternal power and divinity are plainly seen, being perceived by means of things that are made.”[BD] The statement here is very precise. Certain things relating to God are manifest within men’s minds, and are proved by the evidence of His works; these properties of God thus manifested being specially His power or control of all forces, and His divinity or possession of a nature higher than ours. The argument of the writer is that all heathens know this; and, as a matter of fact, I believe it must be admitted even by those most sceptical on such points, that some notion of a divinity has been derived from nature by men of all nations and tribes, if we except, perhaps, a few enlightened positivists of this nineteenth century whom excess of light has made blind. “If the light that is in man be darkness,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-83-2048.jpg)

![how great is that darkness.” But then this notion of a God is a very old and primitive one, and Spencer takes care to inform us that “first thoughts are either wholly out of harmony with things, or in very incomplete harmony with them,” and consequently that old beliefs and generally diffused notions are presumably wrong. [BD] Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, chap i. Is it true, however, that the modern knowledge of nature tends to rob it of a spiritual First Cause? One can conceive such a tendency, if all our advances in knowledge had tended more and more to identify force with matter in its grosser forms, and to remove more and more from our mental view those powers which are not material; but the very reverse of this is the case. Modern discovery has tended more and more to attach importance to certain universally diffused media which do not seem to be subject to the laws of ordinary matter, and to prove at once the Protean character and indestructibility of forces, the aggregate of which, as acting in the universe, gives us our nearest approach to the conception of physical omnipotence. This is what so many of our evolutionists mean when they indignantly disclaim materialism. They know that there is a boundless energy beyond mere matter, and of which matter seems the sport and toy. Could they conceive of this energy as the expression of a personal will, they would become theists. Man himself presents a microcosm of matter and force, raised to a higher plane than that of the merely chemical and physical. In him we find not merely that brain and nerve force which is common to him and lower animals, and which exhibits one of the most marvellous energies in nature, but we have the higher force of will and intellect, enabling him to read the secrets of nature, to seize and combine and utilize its laws like a god, and like a god to attain to the higher discernment of good and evil. Nay, more, this power which resides within man rules with omnipotent energy the material organism, driving its nerve forces until cells and fibres are worn out and destroyed, taxing muscles and tendons till they break, impelling its slave the body even to that which will bring injury and death itself. Surely, what we thus see in man must be the image and likeness of the Great Spirit. We can escape from this](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-84-2048.jpg)

![creation. Man himself has by some naturalists been divided into several species; but we may well be content to believe the creation of one primitive form, and the production of existing races by variation. Every zoologist and botanist who has studied any group of animals or plants with care, knows that there are numerous related forms passing into each other, which some naturalists might consider to be distinct species, but which it is certainly not necessary to regard as distinct products of creation. Every species is more or less variable, and this variability may be developed by different causes. Individuals exposed to unfavourable conditions will be stunted and depauperated; those in more favourable circumstances may be improved and enlarged. Important changes may thus take place without transgressing the limits of the species, or preventing a return to its typical forms; and the practice of confounding these more limited changes with the wider structural and physiological differences which separate true species is much to be deprecated. Animals which pass through metamorphoses, or which, are developed through the instrumentality of intermediate forms or “nurses”[BE] are not only liable to be separated by mistake into distinct species, but they may, tinder certain circumstances, attain to a premature maturity, or may be fixed for a time or permanently in an immature condition. Further, species, like individuals, probably have their infancy, maturity, and decay in geological time, and may present differences in these several stages. It is the remainder of true specific types left after all these sources of error are removed, that creation has to account for; and to arrive at this remainder, and to ascertain its nature and amount, will require a vast expenditure of skilful and conscientious labour. [BE] Mr. Mungo Ponton, in his book “The Beginning,” has based a theory of derivation on this peculiarity. 3. Since animals and plants have been introduced upon our earth in long succession throughout geologic time, and this in a somewhat regular manner, we have a right to assume that their introduction has been in accordance with a law or plan of creation, and that this may have included the co-operation of many efficient causes, and may have differed in its application to different cases. This is a very old doctrine of theology, for it appears in the early chapters of Genesis. There the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2384214-250605121547-a9db2783/75/Compositional-Semantics-An-Introduction-To-The-Syntaxsemantics-Interface-Pauline-Jacobson-89-2048.jpg)