This document contains important information regarding the Rails version used in the book, which is Rails 2.2.2, and notes potential incompatibilities with future releases. It also provides instructions on determining the Rails version in use and directs readers to a wiki for any necessary code updates. Furthermore, the book covers various aspects of web application development using Rails, including architecture, installation, and practical tasks.

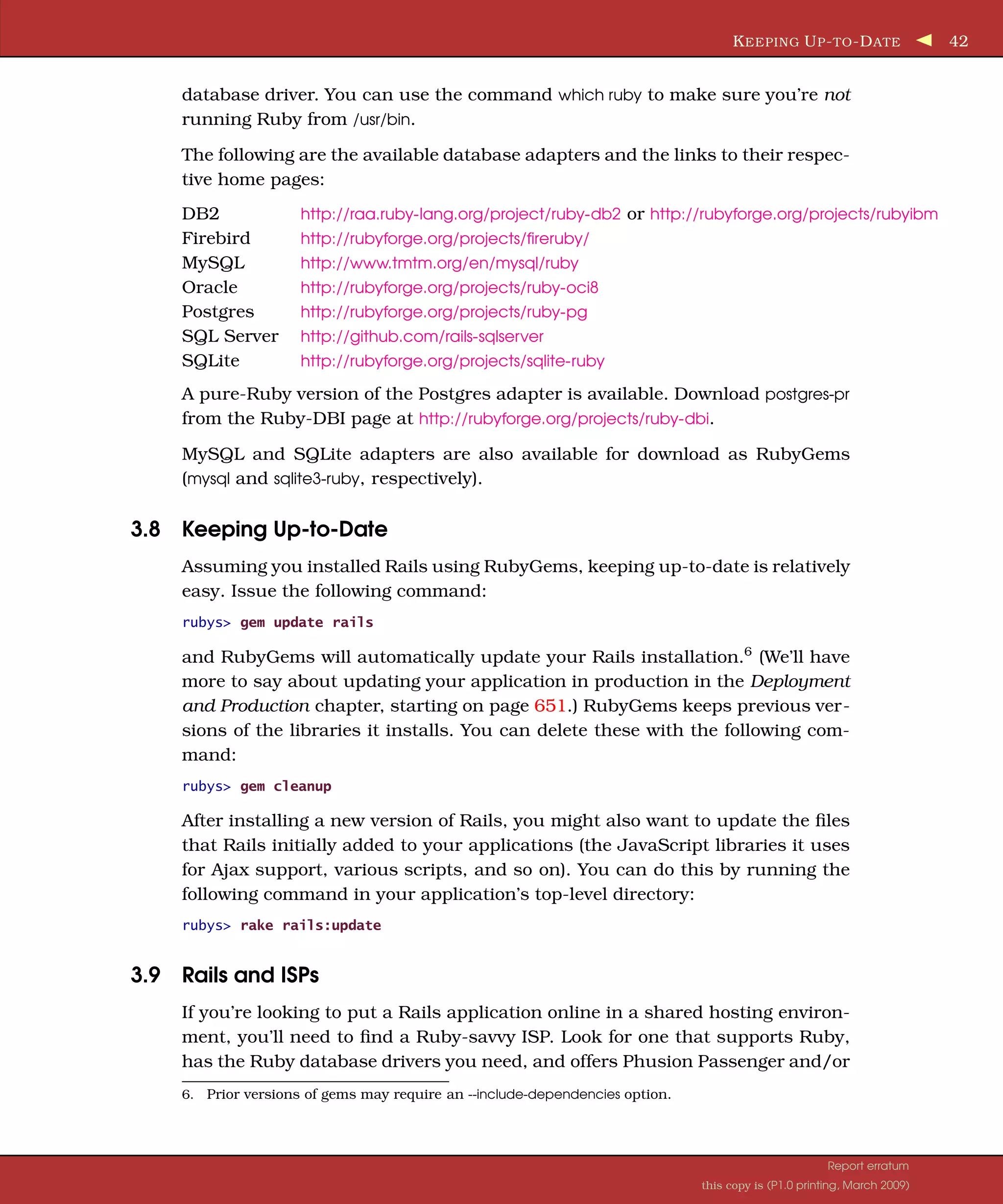

![C REATING A N EW A PPLICATION 45 create app/helpers create app/models : : : create log/development.log create log/test.log work> The command has created a directory named demo. Pop down into that direc- tory, and list its contents (using ls on a Unix box or dir under Windows). You should see a bunch of files and subdirectories: work> cd demo demo> ls -p README config/ lib/ script/ vendor/ Rakefile db/ log/ test/ app/ doc/ public/ tmp/ All these directories (and the files they contain) can be intimidating to start with, but we can ignore most of them for now. In this chapter, we’ll use only two of them directly: the app directory, where we’ll write our application, and the script directory, which contains some useful utility scripts. Let’s start in the script subdirectory. One of the scripts it contains is called server. This script starts a stand-alone web server that can run our newly cre- ated Rails application under WEBrick.2 So, without further ado, let’s start our demo application: demo> ruby script/server => Booting WEBrick... => Rails application started on http://0.0.0.0:3000 => Ctrl-C to shutdown server; call with --help for options [2006-01-08 21:44:10] INFO WEBrick 1.3.1 [2006-01-08 21:44:10] INFO ruby 1.8.2 (2004-12-30) [powerpc-darwin8.2.0] [2006-01-08 21:44:11] INFO WEBrick::HTTPServer#start: pid=10138 port=3000 As the last line of the startup tracing indicates, we just started a web server on port 3000.3 We can access the application by pointing a browser at the URL http://localhost:3000. The result is shown in Figure 4.1. If you look at the window where you started WEBrick, you’ll see tracing show- ing you accessing the application. We’re going to leave WEBrick running in this console window. Later, as we write application code and run it via our browser, 2. WEBrick is a pure-Ruby web server that is distributed with Ruby 1.8.1 and later. Because it is guaranteed to be available, Rails uses it as its development web server. However, if the Mongrel web server is installed on your system (and Rails can find it), the script/server command will use it in preference to WEBrick. You can force Rails to use WEBrick by providing an option to the following command: demo>ruby script/server webrick 3. The 0.0.0.0 part of the address means that WEBrick will accept connections on all interfaces. On Dave’s OS X system, that means both local interfaces (127.0.0.1 and ::1) and his LAN connection. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-45-2048.jpg)

![C REATING THE P RODUCTS M ODEL AND M AINTENANCE A PPLICATION 78 First, we’ll start a local WEBrick-based web server, supplied with Rails: depot> ruby script/server => Booting WEBrick... => Rails application started on http://0.0.0.0:3000 => Ctrl-C to shutdown server; call with --help for options [2008-03-27 11:54:55] INFO WEBrick 1.3.1 [2008-03-27 11:54:55] INFO ruby 1.8.6 (2007-09-24) [i486-linux] [2008-03-27 11:54:55] INFO WEBrick::HTTPServer#start: pid=6200 port=3000 Just as it did with our demo application in Chapter 4, Instant Gratification, this command starts a web server on our local host, port 3000.9 Let’s connect to it. Remember, the URL we give to our browser contains both the port number (3000) and the name of the controller in lowercase (products). That’s pretty boring. It’s showing us an empty list of products. Let’s add some. Click the New product link, and a form should appear. Go ahead and fill it in: 9. You might get an error saying Address already in use when you try to run WEBrick. That simply means that you already have a Rails WEBrick server running on your machine. If you’ve been following along with the examples in the book, that might well be the “Hello, World!” application from Chapter 4. Find its console, and kill the server using Ctrl-C. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-78-2048.jpg)

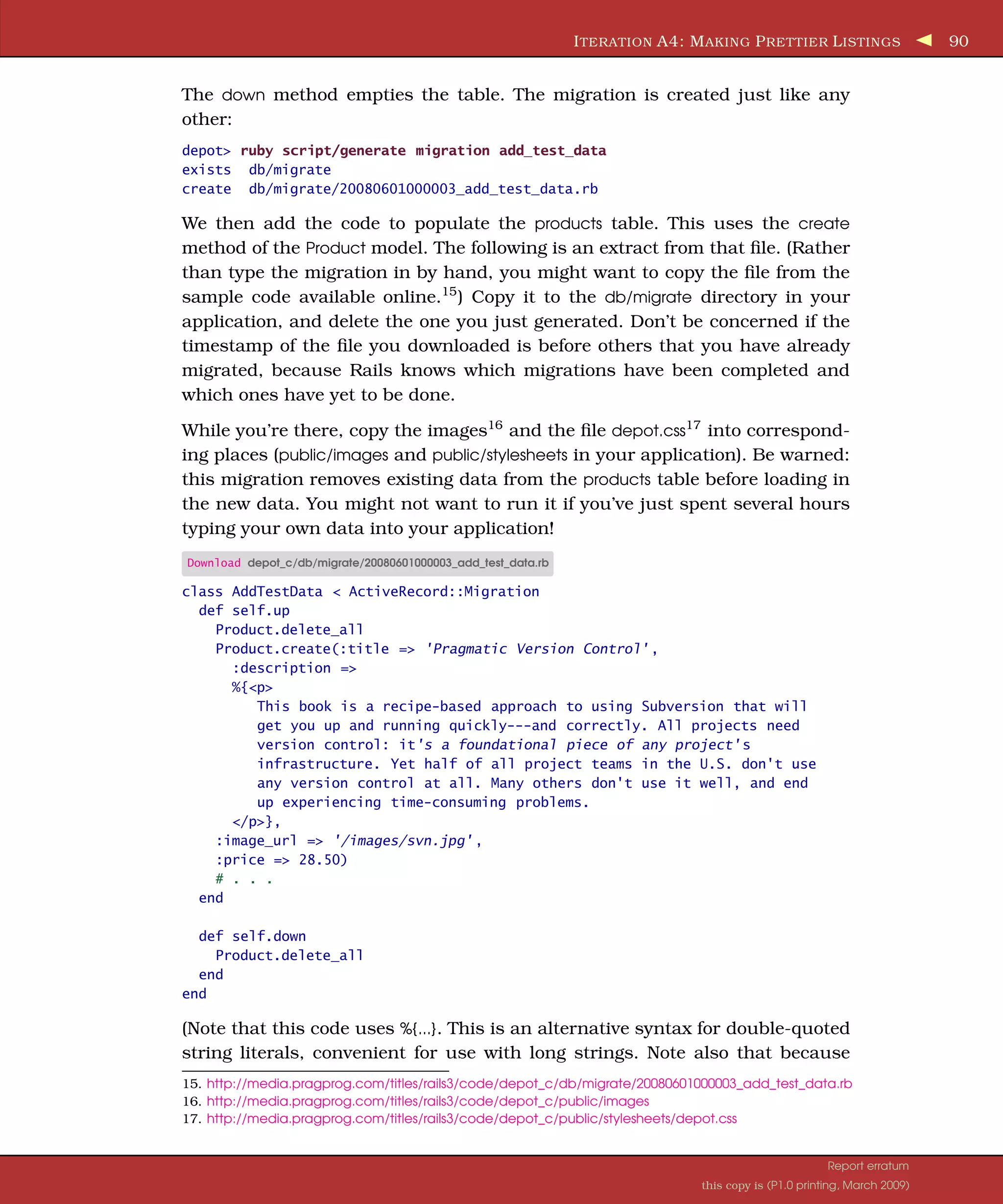

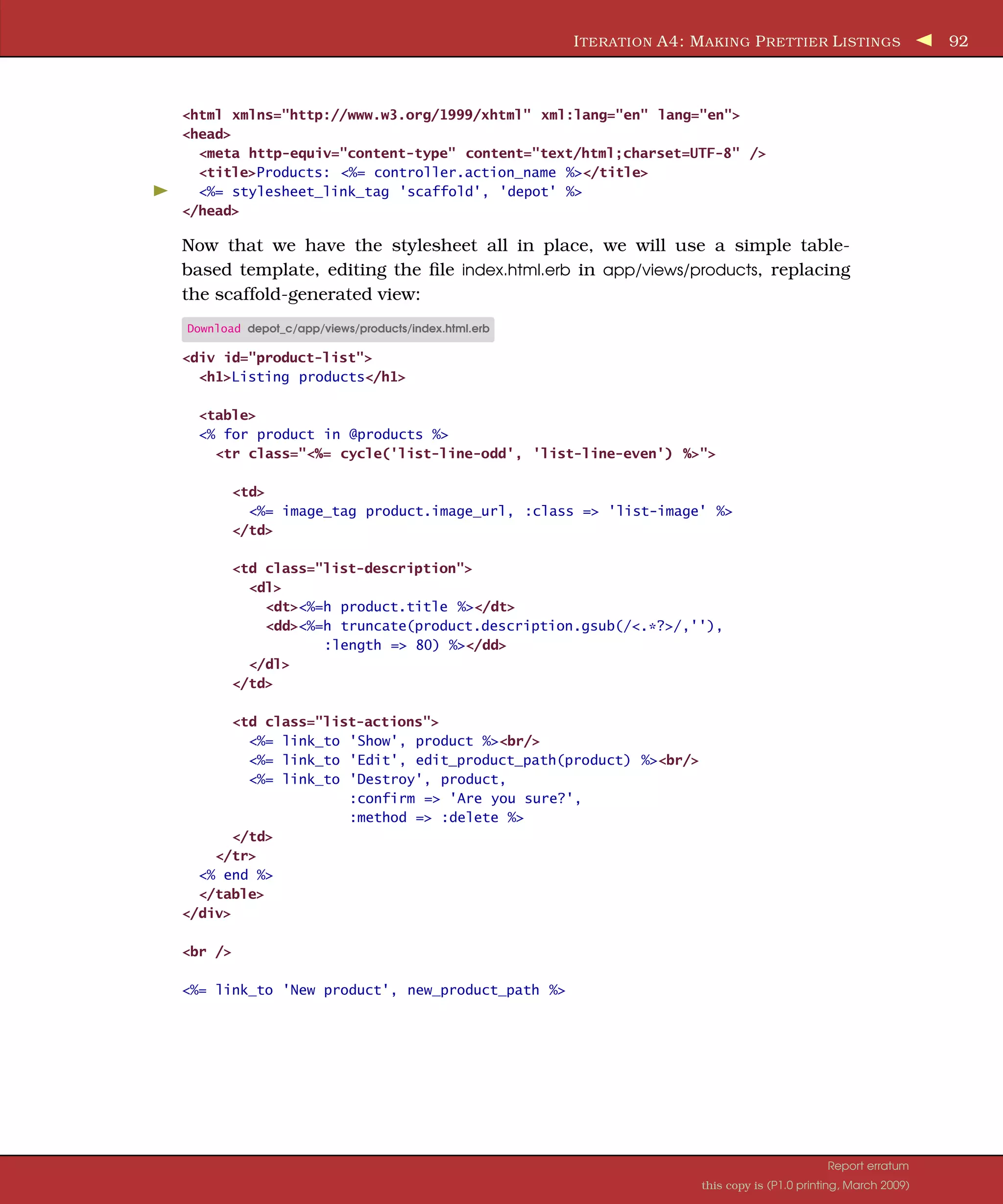

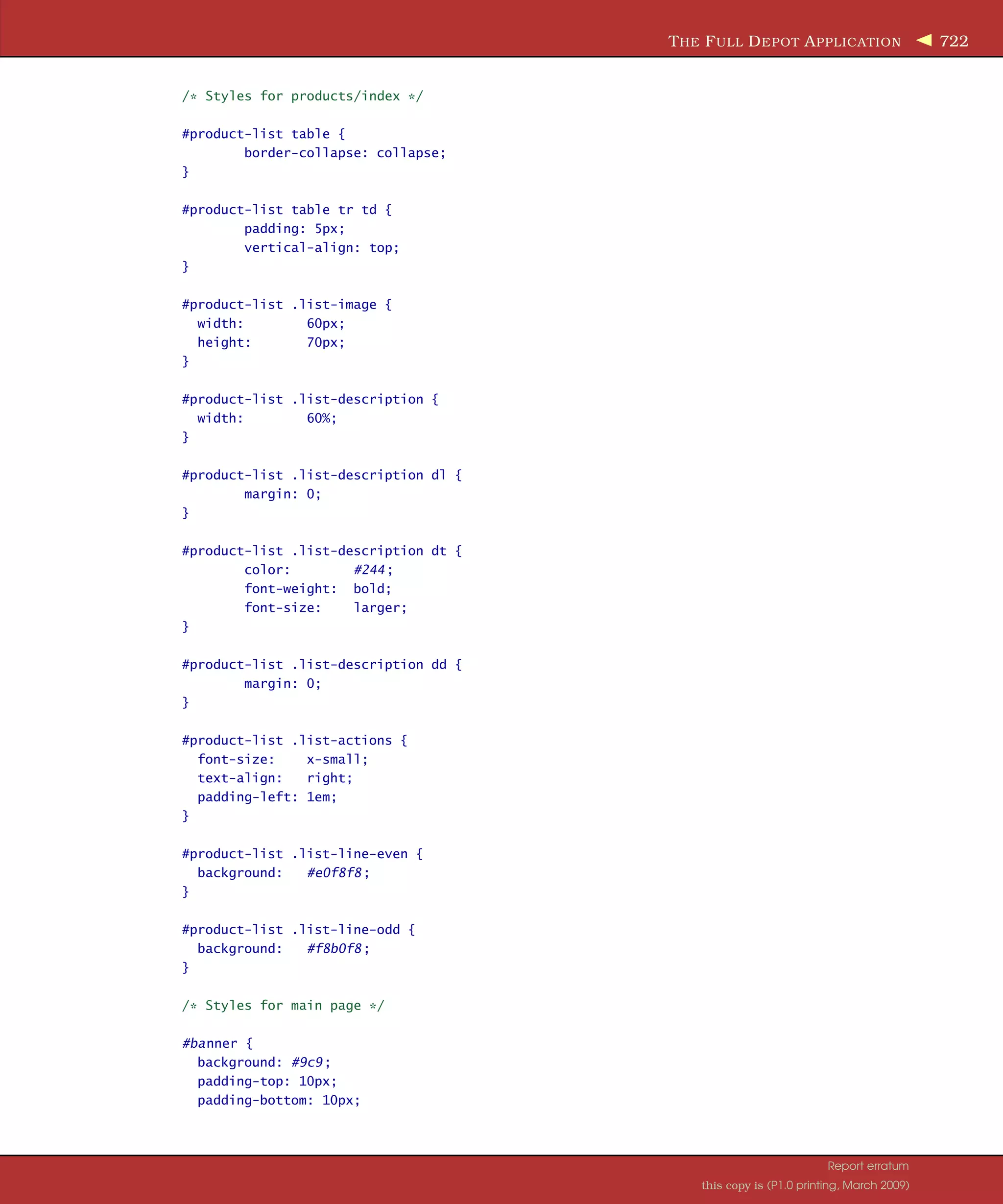

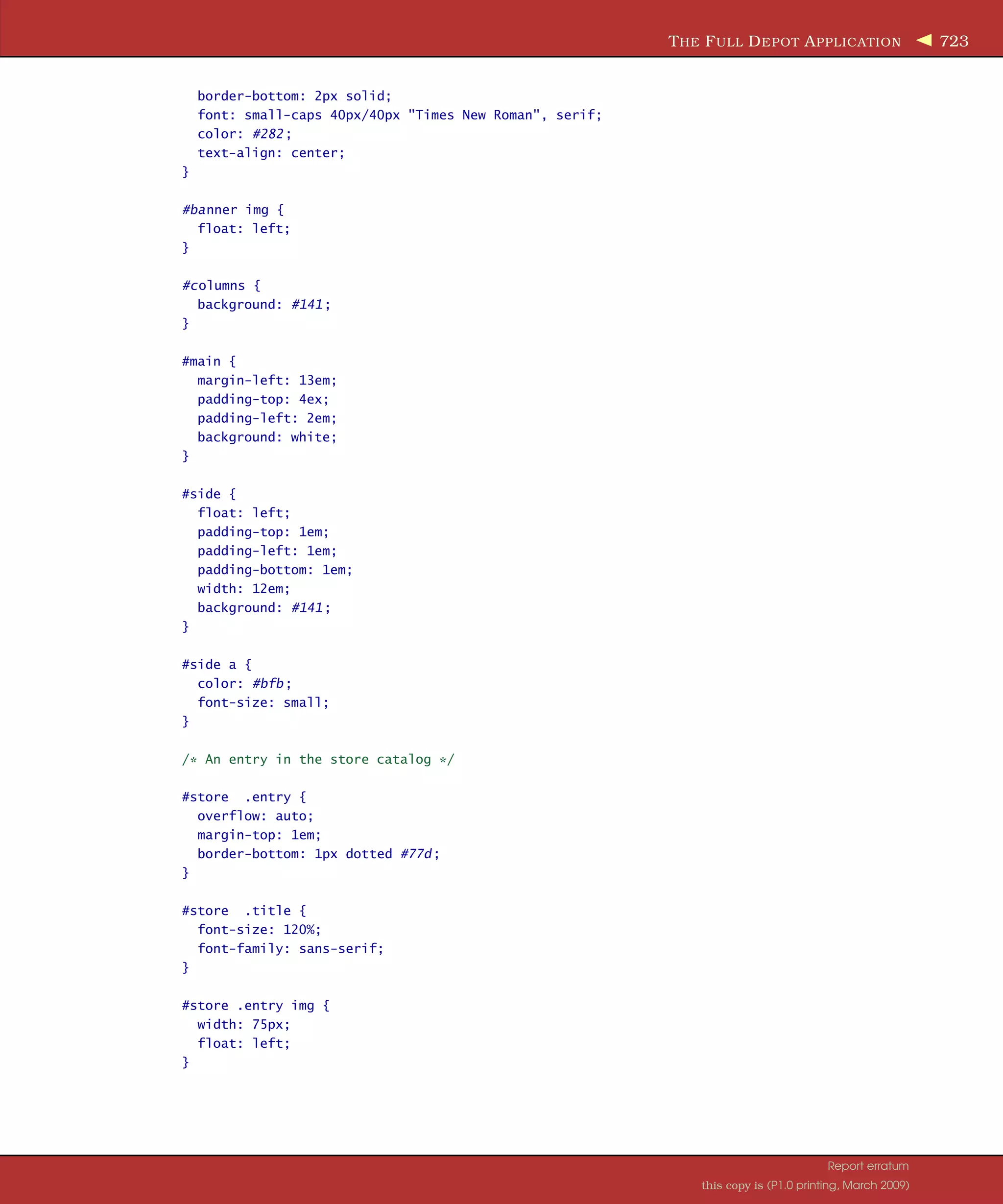

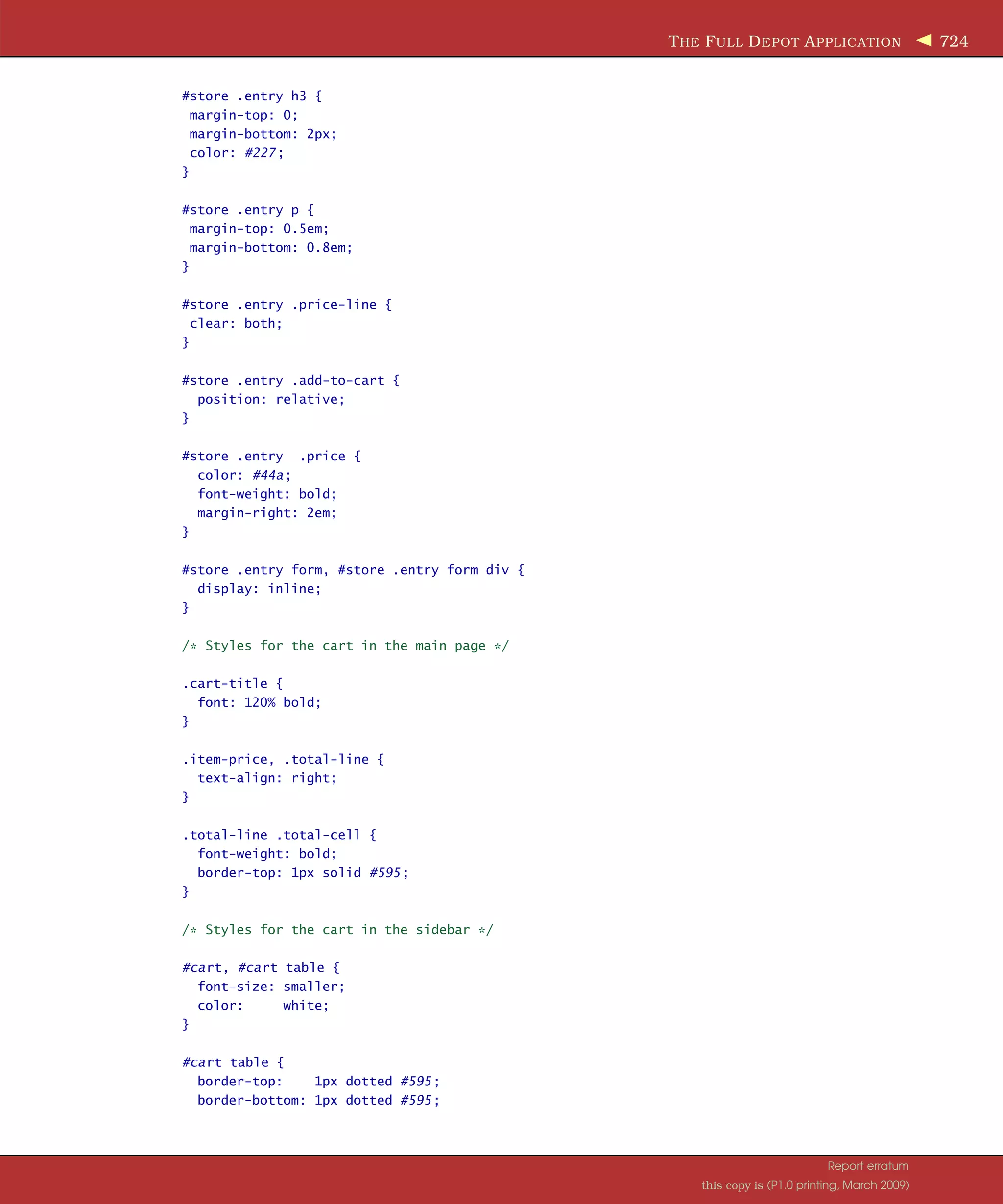

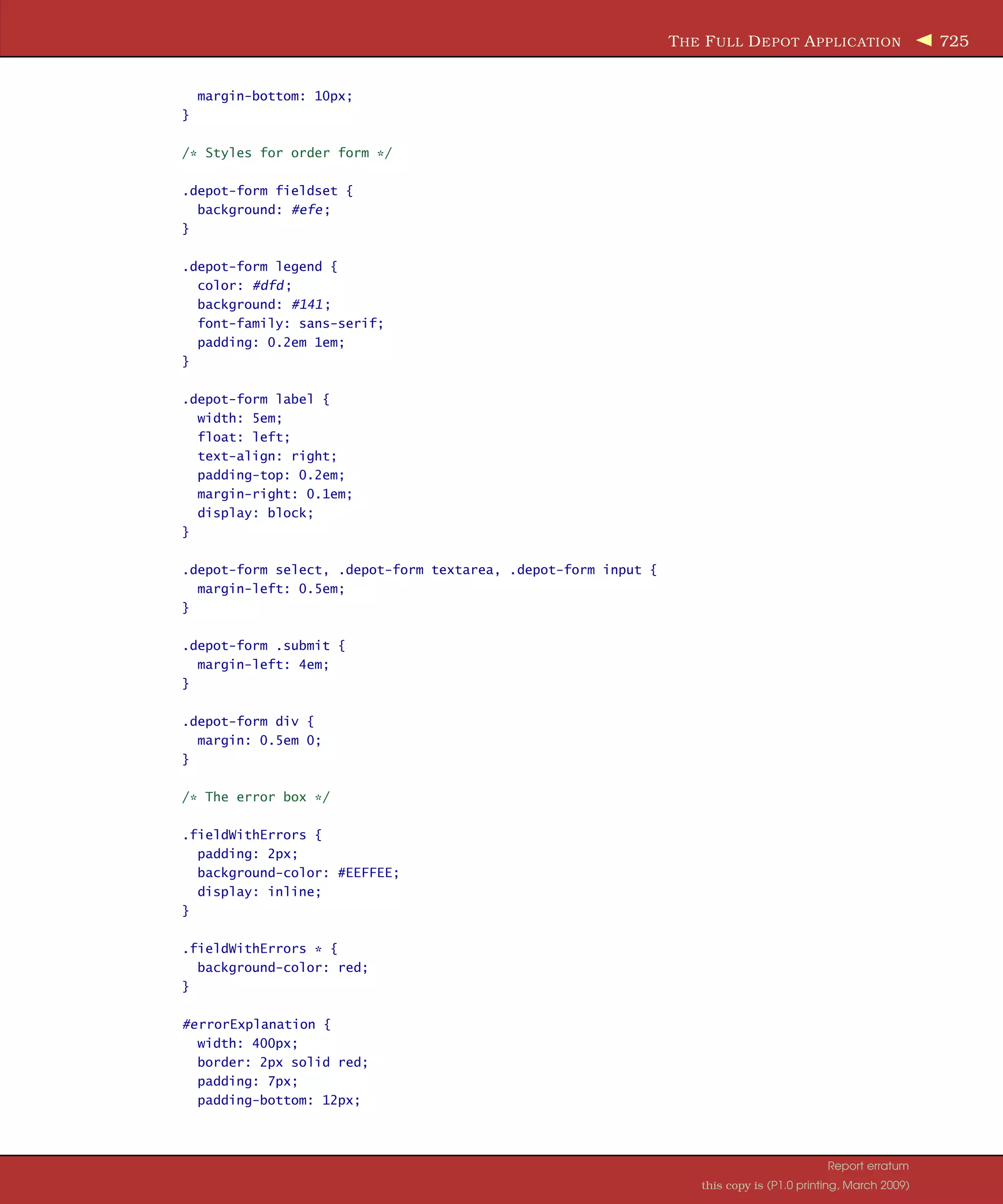

![I TERATION A4: M AKING P RETTIER L ISTINGS 91 it uses Rails’ create method, it will fail silently if records cannot be inserted because of validation errors.) Running the migration will populate your products table with test data: depot> rake db:migrate Now let’s get the product listing tidied up. There are two pieces to this. Even- tually we’ll be writing some HTML that uses CSS to style the presentation. But for this to work, we’ll need to tell the browser to fetch the stylesheet. We need somewhere to put our CSS style definitions. All scaffold-generated applications use the stylesheet scaffold.css in the directory public/stylesheets. Rather than alter this file, we created a new application stylesheet, depot.css, and put it in the same directory. A full listing of this stylesheet starts on page 721. Finally, we need to link these stylesheets into our HTML page. If you look at the .html.erb files we’ve created so far, you won’t find any reference to stylesheets. You won’t even find the HTML <head> section where such references would normally live. Instead, Rails keeps a separate file that is used to create a stan- dard page environment for all product pages. This file, called products.html.erb, is a Rails layout and lives in the layouts directory: Download depot_b/app/views/layouts/products.html.erb Line 1 <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" - "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd" > - - <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xml:lang="en" lang="en"> 5 <head> - <meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html;charset=UTF-8" /> - <title>Products: <%= controller.action_name %></title> - <%= stylesheet_link_tag 'scaffold' %> - </head> 10 <body> - - <p style="color: green"><%= flash[:notice] %></p> - - <%= yield %> 15 - </body> - </html> The eighth line loads the stylesheet. It uses stylesheet_link_tag to create an HTML <link> tag, which loads the standard scaffold stylesheet. We’ll simply add our depot.css file here (dropping the .css extension). Don’t worry about the rest of the file; we’ll look at that later. Download depot_c/app/views/layouts/products.html.erb <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd" > Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-91-2048.jpg)

![S ESSIONS 108 The setup is done in the same environment.rb file in the config directory: Download depot_f/config/environment.rb config.action_controller.session = { :session_key => '_depot_session' , :secret => 'f914e9b1bbdb829688de8512f...9b1810a4e238a61dfd922dc9dd62521' } By choosing something other than the cookie store, you do however have one more action you will need to take. You will need to uncomment the secret by removing the # character from one line in the file application.rb2 in the app/controller directory: Download depot_f/app/controllers/application.rb class ApplicationController < ActionController::Base helper :all # include all helpers, all the time # See ActionController::RequestForgeryProtection for details # Uncomment the :secret if you're not using the cookie session store protect_from_forgery :secret => '8fc080370e56e929a2d5afca5540a0f7' # See ActionController::Base for details # Uncomment this to filter the contents of submitted sensitive data parameters # from your application log (in this case, all fields with names like "password"). # filter_parameter_logging :password end That’s it! The next time you restart your application (stopping and starting script/server), it will store its session data in the database. Why not do that now? Carts and Sessions So, having just plowed through all that theory, where does that leave us in practice? We need to be able to assign a new cart object to a session the first time it’s needed and find that cart object again every time it’s needed in the same session. We can achieve that by creating a method, find_cart, in the store controller. A simple (but verbose) implementation would be as follows: def find_cart unless session[:cart] # if there's no cart in the session session[:cart] = Cart.new # add a new one end session[:cart] # return existing or new cart end Remember that Rails makes the current session look like a hash to the con- troller, so we’ll store the cart in the session by indexing it with the symbol :cart. We don’t currently know just what our cart will be—for now let’s assume that it’s a class, so we can create a new cart object using Cart.new. Armed with all this knowledge, we can now arrange to keep a cart in the user’s session. 2. Starting with Rails 2.3, this file will be named application_controller.rb, and the :secret parameter is no longer needed or supported. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-108-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION C1: C REATING A C AR T 109 It turns out there’s a more idiomatic way of doing the same thing in Ruby: Download depot_f/app/controllers/store_controller.rb private def find_cart session[:cart] ||= Cart.new end This method is fairly tricky. It uses Ruby’s conditional assignment operator, ||=. If the session hash has a value corresponding to the key :cart, that value is ||= ֒ page 678 → returned immediately. Otherwise, a new Cart object is created and assigned to the session. This new Cart is then returned. Note that we make the find_cart method private. This prevents Rails from mak- ing it available as an action on the controller. Be careful as you add methods to this controller as we work further on the cart—if you add them after the private declaration, they’ll be invisible outside the class. New actions must go before the private line. 8.2 Iteration C1: Creating a Cart We’re looking at sessions because we need somewhere to keep our shopping cart. We’ve got the session stuff sorted out, so let’s move on to implement the cart. For now, let’s keep it simple. It holds data and contains some business logic, so we know that it is logically a model. But, do we need a cart database table? Not necessarily. The cart is tied to the buyer’s session, and as long as that session data is available across all our servers (when we finally deploy in a multiserver environment), that’s probably good enough. So for now, we’ll assume the cart is a regular class and see what happens. We’ll use our editor to create the file cart.rb in the app/models directory.3 The implementation is simple. The cart is basically a wrapper for an array of items. When a product is added (using the add_product method), it is appended to the item list: Download depot_f/app/models/cart.rb class Cart attr_reader attr_reader :items ֒ page 671 → def initialize @items = [] end def add_product(product) @items << product end end 3. Note that we don’t use the Rails model generator to create this file. The generator is used only to create database-backed models. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-109-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION C1: C REATING A C AR T 110 Observant readers (yes, that’s all of you) will have noticed that our catalog listing view already includes an Add to Cart button for each product. What we want to do now is to wire it up to an add_to_cart action on the store controller. However, there’s a problem with this: how will the add_to_cart action know which product to add to our cart? We’ll need to pass it the id of the item corresponding to the button. That’s easy enough—we simply add an :id option to the button_to call.4 Our index.html.erb template now looks like this: Download depot_f/app/views/store/index.html.erb <%= button_to "Add to Cart" , :action => 'add_to_cart', :id => product %> This button links to an add_to_cart action in the store controller (and we haven’t written that action yet). It will pass in the product id as a form param- eter. Here’s where we start to see how important the id field is in our models. Rails identifies model objects (and the corresponding database rows) by their id fields. If we pass an id to add_to_cart, we’re uniquely identifying the product to add. Let’s implement the add_to_cart method now. It needs to find the shopping cart for the current session (creating one if there isn’t one there already), add the selected product to that cart, and display the cart contents. So, rather than worry too much about the details, let’s just write the code at this level of abstraction. Here’s the add_to_cart method in app/controllers/store_controller.rb: Download depot_f/app/controllers/store_controller.rb Line 1 def add_to_cart 2 product = Product.find(params[:id]) 3 @cart = find_cart 4 @cart.add_product(product) 5 end On line 2, we use the params object to get the id parameter from the request, then we call the Product model to find the product with that id, and finally we save the result into a local variable named product. The next line uses the find_cart method we implemented on the previous page to find (or create) a cart in the session. Line 4 then adds the product to this cart. The params object is important inside Rails applications. It holds all of the parameters passed in a browser request. By convention, params[:id] holds the id, or the primary key, of the object to be used by an action. We set that id when we used :id => product in the button_to call in our view. Be careful when you add the add_to_cart method to the controller. Because it is called as an action, it must be public and so must be added above the private directive we put in to hide the find_cart method. 4. Saying :id => product is idiomatic shorthand for :id => product.id. Both pass the product’s id back to the controller. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-110-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION C3: H ANDLING E RRORS 115 Figure 8.1: A cart with quantities Anyway, we now have a cart that maintains a count for each of the products that it holds, and we have a view that displays that count. We can see what this looks like in Figure 8.1. Happy that we have something presentable, we call our customer over and show her the result of our morning’s work. She’s pleased—she can see the site starting to come together. However, she’s also troubled, having just read an article in the trade press on the way e-commerce sites are being attacked and compromised daily. She read that one kind of attack involves feeding requests with bad parameters into web applications, hoping to expose bugs and security flaws. She noticed that the link to add an item to our cart looks like store/add_to_cart/nnn, where nnn is our internal product id. Feeling mali- cious, she manually types this request into a browser, giving it a product id of wibble. She’s not impressed when our application displays the page in Fig- ure 8.2, on the following page. This reveals way too much information about our application. It also seems fairly unprofessional. So, it looks as if our next iteration will be spent making the application more resilient. 8.4 Iteration C3: Handling Errors Looking at the page displayed in Figure 8.2, it’s apparent that our application raised an exception at line 16 of the store controller.7 That turns out to be this line: product = Product.find(params[:id]) 7. Your line number might be different. We have some book-related formatting stuff in our source files. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-115-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION C3: H ANDLING E RRORS 117 messages. For example, when our add_to_cart action detects that it was passed an invalid product id, it can store that error message in the flash area and redirect to the index action to redisplay the catalog. The view for the index action can extract the error and display it at the top of the catalog page. The flash information is accessible within the views by using the flash accessor method. Why couldn’t we just store the error in any old instance variable? Remember that after a redirect is sent by our application to the browser, the browser sends a new request back to our application. By the time we receive that request, our application has moved on—all the instance variables from previ- ous requests are long gone. The flash data is stored in the session in order to make it available between requests. Armed with all this background about flash data, we can now change our add_to_cart method to intercept bad product ids and report on the problem: Download depot_h/app/controllers/store_controller.rb def add_to_cart product = Product.find(params[:id]) @cart = find_cart @cart.add_product(product) rescue ActiveRecord::RecordNotFound logger.error("Attempt to access invalid product #{params[:id]}" ) flash[:notice] = "Invalid product" redirect_to :action => 'index' end The rescue clause intercepts the exception raised by Product.find. In the handler, we do the following: • Use the Rails logger to record the error. Every controller has a logger attribute. Here we use it to record a message at the error logging level. • Create a flash notice with an explanation. Just as with sessions, you access the flash as if it were a hash. Here we used the key :notice to store our message. • Redirect to the catalog display using the redirect_to method. This takes a wide range of parameters (similar to the link_to method we encountered in the templates). In this case, it instructs the browser to immediately request the URL that will invoke the current controller’s index action. Why redirect, rather than just display the catalog here? If we redirect, the user’s browser will end up displaying a URL of http://.../store/index, rather than http://.../store/add_to_cart/wibble. We expose less of the application this way. We also prevent the user from retriggering the error by hitting the Reload button. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-117-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION C3: H ANDLING E RRORS 118 With this code in place, we can rerun our customer’s problematic query. This time, when we enter the following URL: http://localhost:3000/store/add_to_cart/wibble we don’t see a bunch of errors in the browser. Instead, the catalog page is dis- played. If we look at the end of the log file (development.log in the log directory), we’ll see our message:9 Parameters: {"action"=>"add_to_cart", "id"=>"wibble", "controller"=>"store"} Product Load (0.000246) SELECT * FROM "products" WHERE ("products"."id" = 0) Attempt to access invalid product wibble Redirected to http://localhost:3000/store/index Completed in 0.00522 (191 reqs/sec) . . . Processing StoreController#index ... : : Rendering within layouts/store Rendering store/index So, the logging worked. But the flash message didn’t appear on the user’s browser. That’s because we didn’t display it. We’ll need to add something to the layout to tell it to display flash messages if they exist. The following html.erb code checks for a notice-level flash message and creates a new <div> contain- ing it if necessary: <% if flash[:notice] -%> <div id="notice"><%= flash[:notice] %></div> <% end -%> So, where do we put this code? We could put it at the top of the catalog display template—the code in index.html.erb. After all, that’s where we’d like it to appear right now. But it would be nice if all pages had a standardized way of displaying errors. 9. On Unix machines, we’d probably use a command such as tail or less to view this file. On Windows, you could use your favorite editor. It’s often a good idea to keep a window open showing new lines as they are added to this file. In Unix you’d use tail -f. You can download a tail command for Windows from http://gnuwin32.sourceforge.net/packages/coreutils.htm or get a GUI-based tool from http://tailforwin32.sourceforge.net/. Finally, some OS X users use Console.app to track log files. Just say open name.log at the command line. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-118-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION C3: H ANDLING E RRORS 119 We’re already using a Rails layout to give all the store pages a consistent look, so let’s add the flash-handling code into that layout. That way if our customer suddenly decides that errors would look better in the sidebar, we can make just one change and all our store pages will be updated. So, our new store layout code now looks as follows: Download depot_h/app/views/layouts/store.html.erb <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd" > <html> <head> <title>Pragprog Books Online Store</title> <%= stylesheet_link_tag "depot" , :media => "all" %> </head> <body id="store"> <div id="banner"> <%= image_tag("logo.png" ) %> <%= @page_title || "Pragmatic Bookshelf" %> </div> <div id="columns"> <div id="side"> <a href="http://www....">Home</a><br /> <a href="http://www..../faq">Questions</a><br /> <a href="http://www..../news">News</a><br /> <a href="http://www..../contact">Contact</a><br /> </div> <div id="main"> <% if flash[:notice] -%> <div id="notice"><%= flash[:notice] %></div> <% end -%> <%= yield :layout %> </div> </div> </body> </html> We’ll also need a new CSS styling rule for the notice box: Download depot_h/public/stylesheets/depot.css #notice { border: 2px solid red; padding: 1em; margin-bottom: 2em; background-color: #f0f0f0 ; font: bold smaller sans-serif; } This time, when we manually enter the invalid product code, we see the error reported at the top of the catalog page. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-119-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION C4: F INISHING THE C AR T 120 Sensing the end of an iteration, we call our customer over and show her that the error is now properly handled. She’s delighted and continues to play with the application. She notices a minor problem on our new cart display—there’s no way to empty items out of a cart. This minor change will be our next itera- tion. We should make it before heading home. 8.5 Iteration C4: Finishing the Cart We know by now that in order to implement the “empty cart” function, we have to add a link to the cart and implement an empty_cart method in the store controller. Let’s start with the template. Rather than use a hyperlink, let’s use the button_to method to put a button on the page: Download depot_h/app/views/store/add_to_cart.html.erb <h2>Your Pragmatic Cart</h2> <ul> <% for item in @cart.items %> <li><%= item.quantity %> × <%=h item.title %></li> <% end %> </ul> <%= button_to 'Empty cart', :action => 'empty_cart' %> In the controller, we’ll implement the empty_cart method. It removes the cart from the session and sets a message into the flash before redirecting to the index page: Download depot_h/app/controllers/store_controller.rb def empty_cart session[:cart] = nil flash[:notice] = "Your cart is currently empty" redirect_to :action => 'index' end Now when we view our cart and click the Empty Cart button, we get taken back to the catalog page, and a nice little message says this: Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-120-2048.jpg)

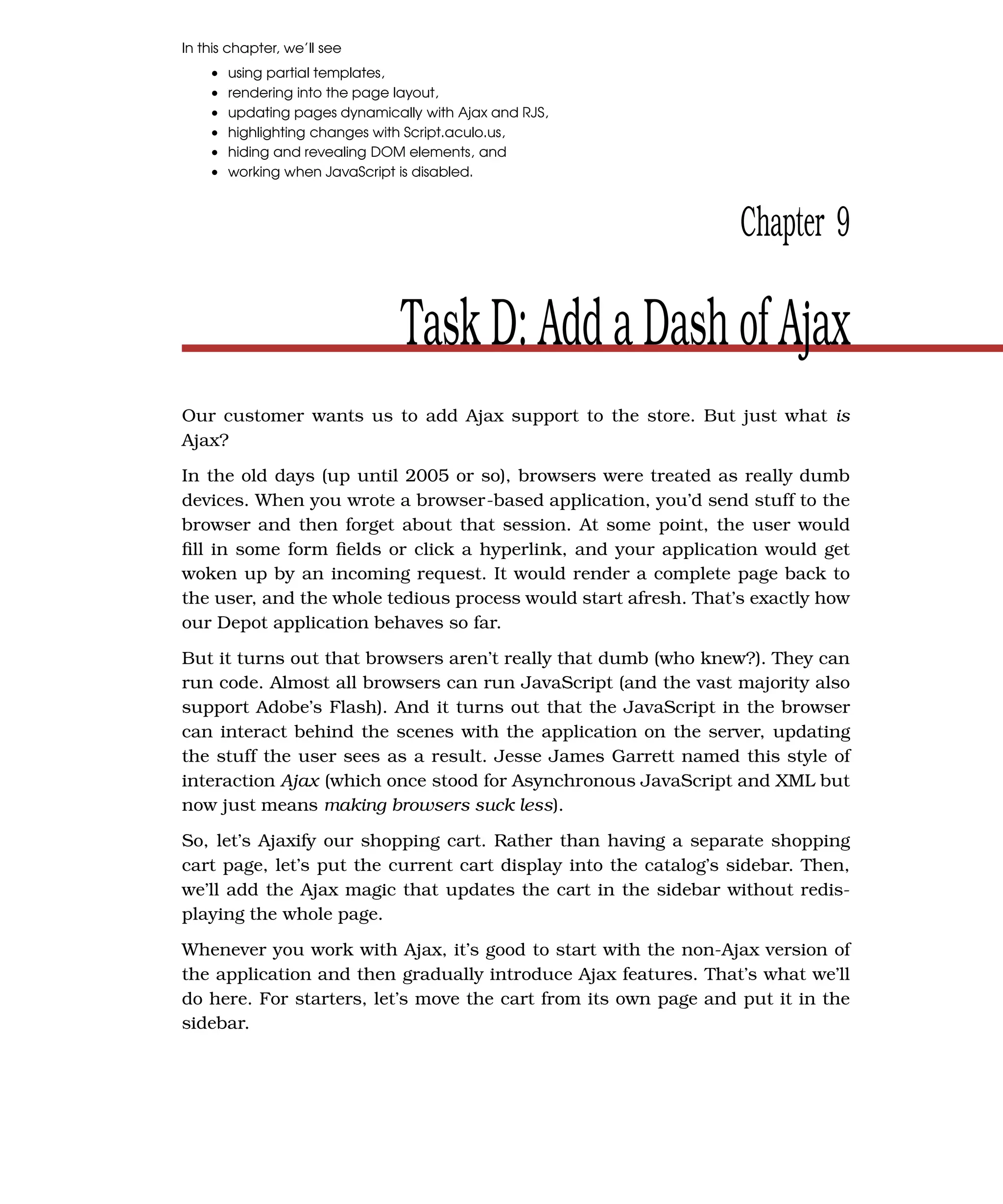

![I TERATION C4: F INISHING THE C AR T 121 However, before we break an arm trying to pat ourselves on the back, let’s look back at our code. We’ve just introduced some duplication. In the store controller, we now have two places that put a message into the flash and redirect to the index page. Sounds like we should extract that com- mon code into a method, so let’s implement redirect_to_index and change the add_to_cart and empty_cart methods to use it: Download depot_i/app/controllers/store_controller.rb def add_to_cart product = Product.find(params[:id]) @cart = find_cart @cart.add_product(product) rescue ActiveRecord::RecordNotFound logger.error("Attempt to access invalid product #{params[:id]}" ) redirect_to_index("Invalid product" ) end def empty_cart session[:cart] = nil redirect_to_index("Your cart is currently empty" ) end private def redirect_to_index(msg) flash[:notice] = msg redirect_to :action => 'index' end And, finally, we’ll get around to tidying up the cart display. Rather than use <li> elements for each item, let’s use a table. Again, we’ll rely on CSS to do the styling: Download depot_i/app/views/store/add_to_cart.html.erb <div class="cart-title">Your Cart</div> <table> <% for item in @cart.items %> <tr> <td><%= item.quantity %>×</td> <td><%=h item.title %></td> <td class="item-price"><%= number_to_currency(item.price) %></td> </tr> <% end %> <tr class="total-line"> <td colspan="2">Total</td> <td class="total-cell"><%= number_to_currency(@cart.total_price) %></td> </tr> </table> <%= button_to "Empty cart" , :action => :empty_cart %> Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-121-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION C4: F INISHING THE C AR T 123 • Using the logger to log events • Removing duplication from controllers We’ve also generated our fair share of errors and seen how to get around them. But, just as we think we’ve wrapped this functionality up, our customer wan- ders over with a copy of Information Technology and Golf Weekly. Apparently, there’s an article about a new style of browser interface, where stuff gets up- dated on the fly. “Ajax,” she says, proudly. Hmmm...let’s look at that tomorrow. Playtime Here’s some stuff to try on your own: • Add a new variable to the session to record how many times the user has accessed the store controller’s index action. The first time through, your count won’t be in the session. You can test for this with code like this: if session[:counter].nil? ... If the session variable isn’t there, you’ll need to initialize it. Then you’ll be able to increment it. • Pass this counter to your template, and display it at the top of the catalog page. Hint: the pluralize helper (described on page 517) might be useful when forming the message you display. • Reset the counter to zero whenever the user adds something to the cart. • Change the template to display the counter only if it is greater than five. (You’ll find hints at http://pragprog.wikidot.com/rails-play-time.) Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-123-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION D1: M OVING THE C AR T 128 <a href="http://www....">Home</a><br /> <a href="http://www..../faq">Questions</a><br /> <a href="http://www..../news">News</a><br /> <a href="http://www..../contact">Contact</a><br /> </div> <div id="main"> <% if flash[:notice] -%> <div id="notice"><%= flash[:notice] %></div> <% end -%> <%= yield :layout %> </div> </div> </body> </html> Now we have to make a small change to the store controller. We’re invoking the layout while looking at the store’s index action, and that action doesn’t currently set @cart. That’s easy enough to remedy: Download depot_j/app/controllers/store_controller.rb def index @products = Product.find_products_for_sale @cart = find_cart end Now we add a bit of CSS: Download depot_j/public/stylesheets/depot.css /* Styles for the cart in the sidebar */ #ca rt, #ca rt table { font-size: smaller; color: white; } #ca rt table { border-top: 1px dotted #595 ; border-bottom: 1px dotted #595 ; margin-bottom: 10px; } If you display the catalog after adding something to your cart, you should see something like Figure 9.1, on the next page. Let’s just wait for the Webby Award nomination. Changing the Flow Now that we’re displaying the cart in the sidebar, we can change the way that the Add to Cart button works. Rather than displaying a separate cart page, all it has to do is refresh the main index page. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-128-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION D1: M OVING THE C AR T 129 Figure 9.1: The cart is in the sidebar. The change is pretty simple: at the end of the add_to_cart action, we simply redirect the browser back to the index: Download depot_k/app/controllers/store_controller.rb def add_to_cart product = Product.find(params[:id]) @cart = find_cart @cart.add_product(product) redirect_to_index rescue ActiveRecord::RecordNotFound logger.error("Attempt to access invalid product #{params[:id]}" ) redirect_to_index("Invalid product" ) end For this to work, we need to change the definition of redirect_to_index to make the message parameter optional: Download depot_k/app/controllers/store_controller.rb def redirect_to_index(msg = nil) flash[:notice] = msg if msg redirect_to :action => 'index' end We should now get rid of the add_to_cart.html.erb template—it’s no longer needed. (What’s more, leaving it lying around might confuse us later in this chapter.) Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-129-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION D2: C REATING AN A JAX -B ASED C AR T 131 You tell form_remote_tag how to invoke your server application using the :url parameter. This takes a hash of values that are the same as the trailing param- eters we passed to button_to. The code inside the Ruby block (between the do and end keywords) is the body of the form. In this case, we have a simple submit button. From the user’s perspective, this page looks identical to the previous one. While we’re dealing with the views, we also need to arrange for our application to send the JavaScript libraries used by Rails to the user’s browser. We’ll talk more about this in Chapter 24, The Web, v2.0, on page 563, but for now let’s just add a call to javascript_include_tag to the <head> section of the store layout: Download depot_l/app/views/layouts/store.html.erb <html> <head> <title>Pragprog Books Online Store</title> <%= stylesheet_link_tag "depot" , :media => "all" %> <%= javascript_include_tag :defaults %> </head> So far, we’ve arranged for the browser to send an Ajax request to our applica- tion. The next step is to have the application return a response. The plan is to create the updated HTML fragment that represents the cart and to have the browser stick that HTML into the DOM1 as a replacement for the cart that’s already there. The first change is to stop the add_to_cart action redirecting to the index display. (We know, we just added that only a few pages back. Now we’re taking it out again. We’re agile, right?) What we are going to replace it with is a call to respond_to telling it that we want to respond with a format of .js.2 Download depot_l/app/controllers/store_controller.rb def add_to_cart product = Product.find(params[:id]) @cart = find_cart @cart.add_product(product) respond_to do |format| format.js end rescue ActiveRecord::RecordNotFound logger.error("Attempt to access invalid product #{params[:id]}" ) redirect_to_index("Invalid product" ) end 1. The Document Object Model. This is the browser’s internal representation of the structure and content of the document being displayed. By manipulating the DOM, we cause the display to change in front of the user’s eyes. 2. This syntax may seem surprising at first, but it is simply a method call that is passing a block as an argument. Blocks are described in Section A.9, Blocks and Iterators, on page 675. We will cover the respond_to method in greater detail in Section 12.1, Responding Appropriately, on page 185. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-131-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION D3: H IGHLIGHTING C HANGES 135 Over in store_controller.rb, we’ll take that information and pass it down to the template by assigning it to an instance variable: Download depot_m/app/controllers/store_controller.rb def add_to_cart product = Product.find(params[:id]) @cart = find_cart @current_item = @cart.add_product(product) respond_to do |format| format.js end rescue ActiveRecord::RecordNotFound logger.error("Attempt to access invalid product #{params[:id]}" ) redirect_to_index("Invalid product" ) end In the _cart_item.html.erb partial, we then check to see whether the item we’re rendering is the one that just changed. If so, we tag it with an id of current_item: Download depot_m/app/views/store/_cart_item.html.erb <% if cart_item == @current_item %> <tr id="current_item"> <% else %> <tr> <% end %> <td><%= cart_item.quantity %>×</td> <td><%=h cart_item.title %></td> <td class="item-price"><%= number_to_currency(cart_item.price) %></td> </tr> As a result of these three minor changes, the <tr> element of the most recently changed item in the cart will be tagged with id="current_item". Now we just need to tell the JavaScript to invoke the highlight effect on that item. We do this in the existing add_to_cart.js.rjs template, adding a call to the visual_effect method: Download depot_m/app/views/store/add_to_cart.js.rjs page.replace_html("cart" , :partial => "cart" , :object => @cart) page[:current_item].visual_effect :highlight, :startcolor => "#88ff88" , :endcolor => "#114411" See how we identified the browser element that we wanted to apply the effect to by passing :current_item to the page? We then asked for the highlight visual effect and overrode the default yellow/white transition with colors that work better with our design. Click to add an item to the cart, and you’ll see the changed item in the cart glow a light green before fading back to merge with the background. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-135-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION D4: H IDING AN E MPTY C AR T 136 9.4 Iteration D4: Hiding an Empty Cart There’s one last request from the customer. Right now, even carts with nothing in them are still displayed in the sidebar. Can we arrange for the cart to appear only when it has some content? But of course! In fact, we have a number of options. The simplest is probably to include the HTML for the cart only if the cart has something in it. We could do this totally within the _cart partial: <% unless cart.items.empty? %> <div class="cart-title" >Your Cart</div> <table> <%= render(:partial => "cart_item" , :collection => cart.items) %> <tr class="total-line" > <td colspan="2" >Total</td> <td class="total-cell" ><%= number_to_currency(cart.total_price) %></td> </tr> </table> <%= button_to "Empty cart" , :action => :empty_cart %> <% end %> Although this works, the user interface is somewhat brutal: the whole side- bar redraws on the transition between a cart that’s empty and a cart with something in it. So, let’s not use this code. Instead, let’s smooth it out a little. The Script.aculo.us effects library contains a number of nice transitions that make elements appear. Let’s use blind_down, which will smoothly reveal the cart, sliding the rest of the sidebar down to make room. Not surprisingly, we’ll use our existing .js.rjs template to call the effect. Because the add_to_cart template is invoked only when we add something to the cart, we know that we have to reveal the cart in the sidebar whenever there is exactly one item in the cart (because that means previously the cart was empty and hence hidden). And, because the cart should be visible before we start the highlight effect, we’ll add the code to reveal the cart before the code that triggers the highlight. The template now looks like this: Download depot_n/app/views/store/add_to_cart.js.rjs page.replace_html("cart" , :partial => "cart" , :object => @cart) page[:cart].visual_effect :blind_down if @cart.total_items == 1 page[:current_item].visual_effect :highlight, :startcolor => "#88ff88" , :endcolor => "#114411" Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-136-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION D4: H IDING AN E MPTY C AR T 138 The Rails generators automatically created a helper file for each of our con- trollers (products and store). The Rails command itself (the one that created the application initially) created the file application_helper.rb. If you like, you can organize your methods into controller-specific helpers, but in reality all helpers are available to all views. For now, we need it just in the store view, so let’s start by putting it there. Let’s take a look at the file store_helper.rb in the helpers directory: module StoreHelper end Let’s write a helper method called hidden_div_if. It takes a condition, an optional set of attributes, and a block. It wraps the output generated by the block in a <div> tag, adding the display: none style if the condition is true. We’d use it in the store layout like this: Download depot_n/app/views/layouts/store.html.erb <% hidden_div_if(@cart.items.empty?, :id => "cart" ) do %> <%= render(:partial => "cart" , :object => @cart) %> <% end %> We’ll write our helper so that it is local to the store controller by adding it to store_helper.rb in the app/helpers directory: Download depot_n/app/helpers/store_helper.rb module StoreHelper def hidden_div_if(condition, attributes = {}, &block) if condition attributes["style" ] = "display: none" end content_tag("div" , attributes, &block) end end This code uses the Rails standard helper, content_tag, which can be used to wrap the output created by a block in a tag. By using the &block notation, we get Ruby to pass the block that was given to hidden_div_if down to content_tag. And, finally, we need to stop setting the message in the flash that we used to display when the user empties a cart. It really isn’t needed anymore, because the cart clearly disappears from the sidebar when the catalog index page is redrawn. But there’s another reason to remove it, too. Now that we’re using Ajax to add products to the cart, the main page doesn’t get redrawn between requests as people shop. That means we’ll continue to display the flash mes- sage saying the cart is empty even as we display a cart in the sidebar. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-138-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION D5: D EGRADING I F J AVASCRIPT I S D ISABLED 139 Download depot_n/app/controllers/store_controller.rb def empty_cart session[:cart] = nil redirect_to_index end Although this might seem like a lot of steps, it really isn’t. All we did to make the cart hide and reveal itself was to make the CSS display style conditional on the number of items in the cart and to use the RJS template to invoke the blind_down effect when the cart went from being empty to having one item. Everyone is excited to see our fancy new interface. In fact, because our com- puter is on the office network, our colleagues point their browsers at our test application and try it for themselves. Lots of low whistles follow as folks mar- vel at the way the cart appears and then updates. Everyone loves it. Everyone, that is, except Bruce. Bruce doesn’t trust JavaScript running in his browser and has it turned off. And, with JavaScript disabled, all our fancy Ajax stops working. When Bruce adds something to his cart, he sees something strange: $("cart" ).update("<h1>Your Cart</h1>nn<ul>n n <li id="current_item">nn 3 × Pragmatic Project Automationn</li>n</ul>n n<form method="post" action="/store/empty_cart" class="button-to... Clearly this won’t do. We need to have our application work if our users have disabled JavaScript in their browsers. That’ll be our next iteration. 9.5 Iteration D5: Degrading If Javascript Is Disabled Remember, back on page 128, that we arranged for the cart to appear in the sidebar? We did this before we added a line of Ajax code to the application. If we could fall back to this behavior when JavaScript is disabled in the browser, then the application would work for Bruce in addition to our other co-workers. This basically means that if the incoming request to add_to_cart doesn’t come from JavaScript, we want to do what the original application did and redirect to the index page. When the index displays, the updated cart will appear in the sidebar. If a user clicks the button inside a form_remote_tag, one of two things happens. If JavaScript is disabled, the target action in the application is invoked using a regular HTTP POST request—it acts just like a regular HTML form. If, however, JavaScript is enabled, it overrides this conventional POST and instead uses a JavaScript object to establish a back channel with the server. This object is an instance of class XmlHTTPRequest. Because that’s a mouthful, most folks (and Rails) abbreviate it to xhr. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-139-2048.jpg)

![W HAT W E J UST D ID 140 So, on the server, we can tell that we’re talking to a JavaScript-enabled browser by testing to see whether the incoming request was generated by an xhr object. And the Rails request object, available inside controllers and views, makes it easy to test for this condition. It provides an xhr? method. As a result, making our application work regardless of whether JavaScript is enabled requires only two lines of code in the add_to_cart action: Download depot_o/app/controllers/store_controller.rb def add_to_cart product = Product.find(params[:id]) @cart = find_cart @current_item = @cart.add_product(product) respond_to do |format| format.js if request.xhr? format.html {redirect_to_index} end rescue ActiveRecord::RecordNotFound logger.error("Attempt to access invalid product #{params[:id]}" ) redirect_to_index("Invalid product" ) end 9.6 What We Just Did In this iteration we added Ajax support to our cart: • We moved the shopping cart into the sidebar. We then arranged for the add_to_cart action to redisplay the catalog page. • We used form_remote_tag to invoke the add_to_cart action using Ajax. • We then used an RJS template to update the page with just the cart’s HTML. • To help the user see changes to the cart, we added a highlight effect, again using the RJS template. • We wrote a helper method that hides the cart when it is empty and used the RJS template to reveal it when an item is added. • Finally, we made our application work when the user’s browser has JavaScript disabled by reverting to the behavior we implemented before starting on the Ajax journey. The key point to take away is the incremental style of Ajax development. Start with a conventional application, and then add Ajax features, one by one. Ajax can be hard to debug: by adding it slowly to an application, you make it easier to track down what changed if your application stops working. And, as we saw, starting with a conventional application makes it easier to support both Ajax and non-Ajax behavior in the same codebase. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-140-2048.jpg)

![W HAT W E J UST D ID 141 Finally, we’ll give you a couple of hints. First, if you plan to do a lot of Ajax development, you’ll probably need to get familiar with your browser’s Java- Script debugging facilities and with its DOM inspectors. Chapter 8 of Pragmatic Ajax: A Web 2.0 Primer [GGA06] has a lot of useful tips. And, second, the NoScript plug-in for Firefox makes checking JavaScript/no JavaScript a one- click breeze. Others find it useful to run two different browsers when they are developing—have JavaScript enabled in one, disabled in the other. Then, as new features are added, poking at it with both browsers will make sure your application works regardless of the state of JavaScript. Playtime Here’s some stuff to try on your own: • In Section 7.4, Playtime, on page 103, one of the activities was to make clicking the image add the item to the cart. Change this to use form_ remote_tag and image_submit_tag. • The cart is currently hidden when the user empties it by redrawing the entire catalog. Can you change the application to use the Script.aculo.us blind_up effect instead? • Does the change you made work if the browser has JavaScript disabled? • Experiment with other visual effects for new cart items. For example, can you set their initial state to hidden and then have them grow into place? Does this make it problematic to share the cart item partial between the Ajax code and the initial page display? • Add a link next to each item in the cart. When clicked, it should invoke an action to decrement the quantity of the item, deleting it from the cart when the quantity reaches zero. Get it working without using Ajax first, and then add the Ajax goodness. (You’ll find hints at http://pragprog.wikidot.com/rails-play-time.) Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-141-2048.jpg)

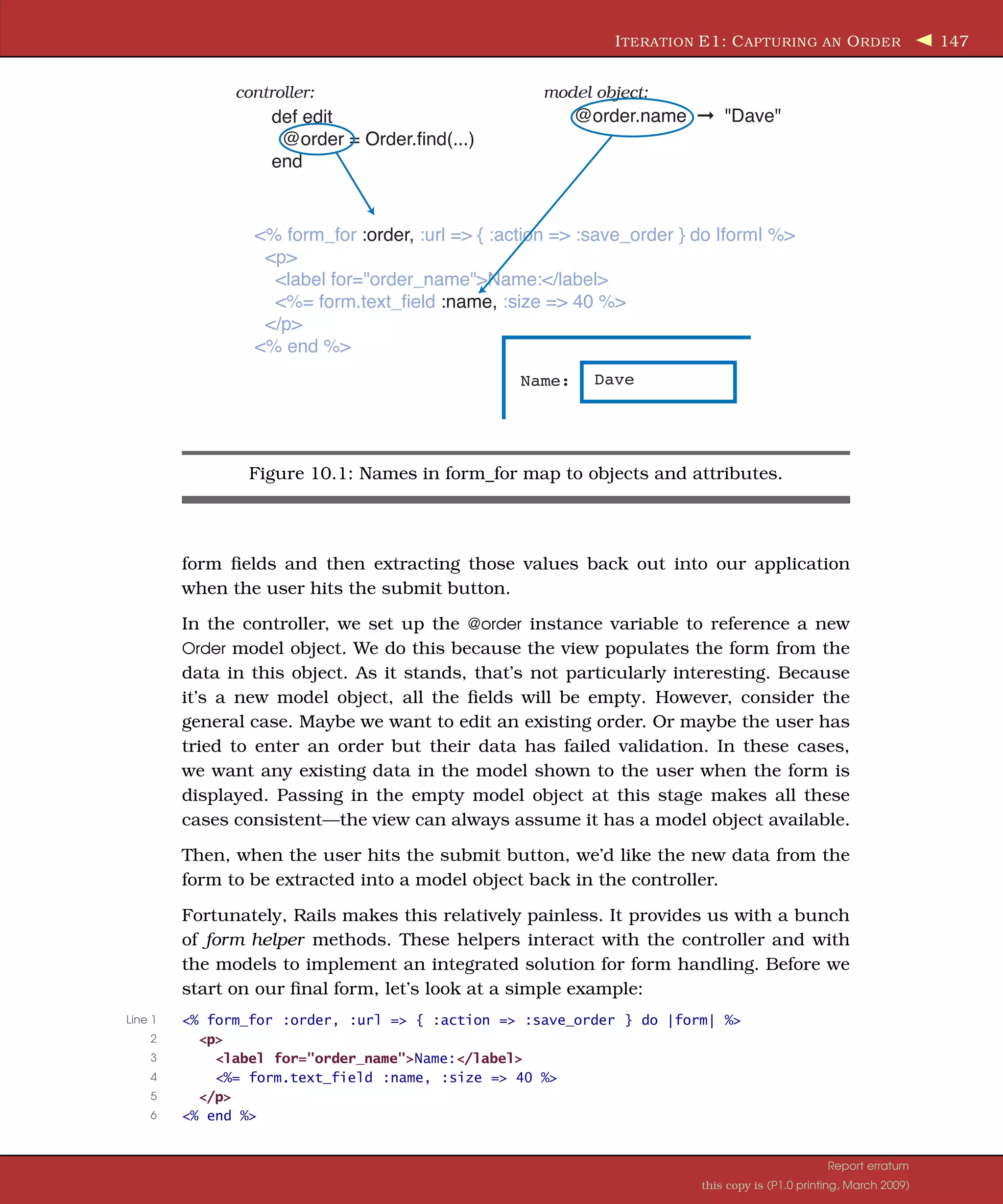

![I TERATION E1: C APTURING AN O RDER 149 <div> <%= form.label :email, "E-Mail:" %> <%= form.text_field :email, :size => 40 %> </div> <div> <%= form.label :pay_type, "Pay with:" %> <%= form.select :pay_type, Order::PAYMENT_TYPES, :prompt => "Select a payment method" %> </div> <%= submit_tag "Place Order" , :class => "submit" %> </fieldset> <% end %> </div> The only tricky thing in there is the code associated with the selection list. We’ve assumed that the list of available payment options is an attribute of the Order model—it will be an array of arrays in the model file. The first element of each subarray is the string to be displayed as the option in the selection, and the second value gets submitted in the request and ultimately is what is stored in the database.3 We’d better define the option array in the model order.rb before we forget: Download depot_p/app/models/order.rb class Order < ActiveRecord::Base PAYMENT_TYPES = [ # Displayed stored in db [ "Check" , "check" ], [ "Credit card" , "cc" ], [ "Purchase order" , "po" ] ] # ... In the template, we pass this array of payment type options to the select helper. We also pass the :prompt parameter, which adds a dummy selection containing the prompt text. 3. If we anticipate that other non-Rails applications will update the orders table, we might want to move the list of payment types into a separate lookup table and make the payment type column a foreign key referencing that new table. Rails provides good support for generating selection lists in this context too. You simply pass the select helper the result of doing a find(:all) on your lookup table. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-149-2048.jpg)

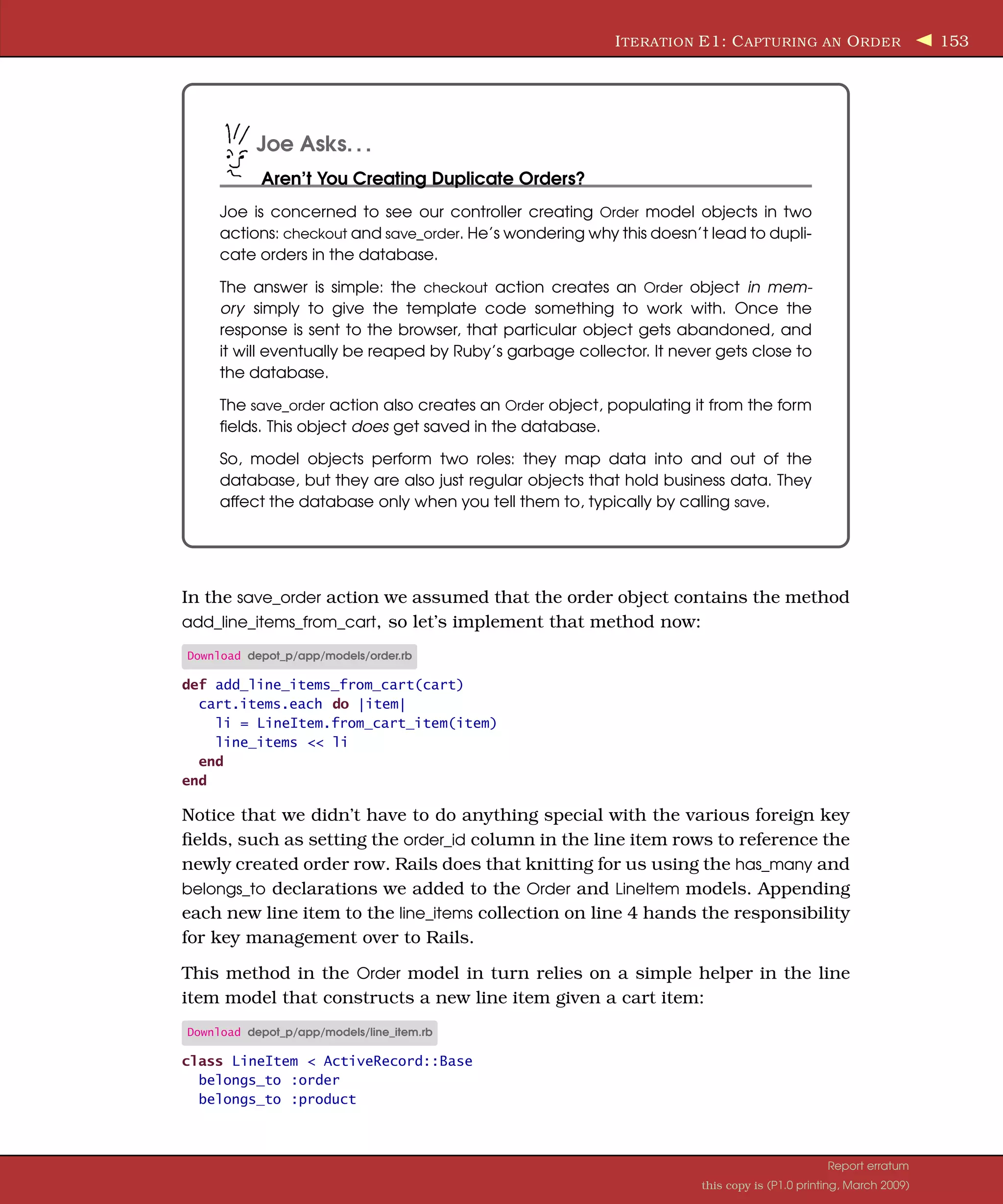

![I TERATION E1: C APTURING AN O RDER 151 Figure 10.2: Our checkout screen We also validate that the payment type is one of the accepted values.4,5 Download depot_p/app/models/order.rb class Order < ActiveRecord::Base PAYMENT_TYPES = [ # Displayed stored in db [ "Check" , "check" ], [ "Credit card" , "cc" ], [ "Purchase order" , "po" ] ] validates_presence_of :name, :address, :email, :pay_type validates_inclusion_of :pay_type, :in => PAYMENT_TYPES.map {|disp, value| value} # ... Note that we already call the error_messages_for helper at the top of the page. 4. To get the list of valid payment types, we take our array of arrays and use the Ruby map method to extract just the values. 5. Some folks might be wondering why we bother to validate the payment type, given that its value comes from a drop-down list that contains only valid values. We do it because an application can’t assume that it’s being fed values from the forms it creates. Nothing is stopping a malicious user from submitting form data directly to the application, bypassing our form. If the user set an unknown payment type, they might conceivably get our products for free. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-151-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION E1: C APTURING AN O RDER 152 This will report validation failures (but only after we’ve written one more chunk of code). Capturing the Order Details Let’s implement the save_order action in the controller. This method has to do the following: 1. Capture the values from the form to populate a new Order model object. 2. Add the line items from our cart to that order. 3. Validate and save the order. If this fails, display the appropriate mes- sages, and let the user correct any problems. 4. Once the order is successfully saved, redisplay the catalog page, includ- ing a message confirming that the order has been placed. The method ends up looking something like this: Download depot_p/app/controllers/store_controller.rb Line 1 def save_order - @cart = find_cart - @order = Order.new(params[:order]) - @order.add_line_items_from_cart(@cart) 5 if @order.save - session[:cart] = nil - redirect_to_index("Thank you for your order" ) - else - render :action => 'checkout' 10 end - end On line 3, we create a new Order object and initialize it from the form data. In this case, we want all the form data related to order objects, so we select the :order hash from the parameters (this is the name we passed as the first parameter to form_for). The next line adds into this order the items that are already stored in the cart—we’ll write the actual method to do this in a minute. Next, on line 5, we tell the order object to save itself (and its children, the line items) to the database. Along the way, the order object will perform validation (but we’ll get to that in a minute). If the save succeeds, we do two things. First, we ready ourselves for this customer’s next order by deleting the cart from the session. Then, we redisplay the catalog using our redirect_to_index method to display a cheerful message. If, instead, the save fails, we redisplay the checkout form. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-152-2048.jpg)

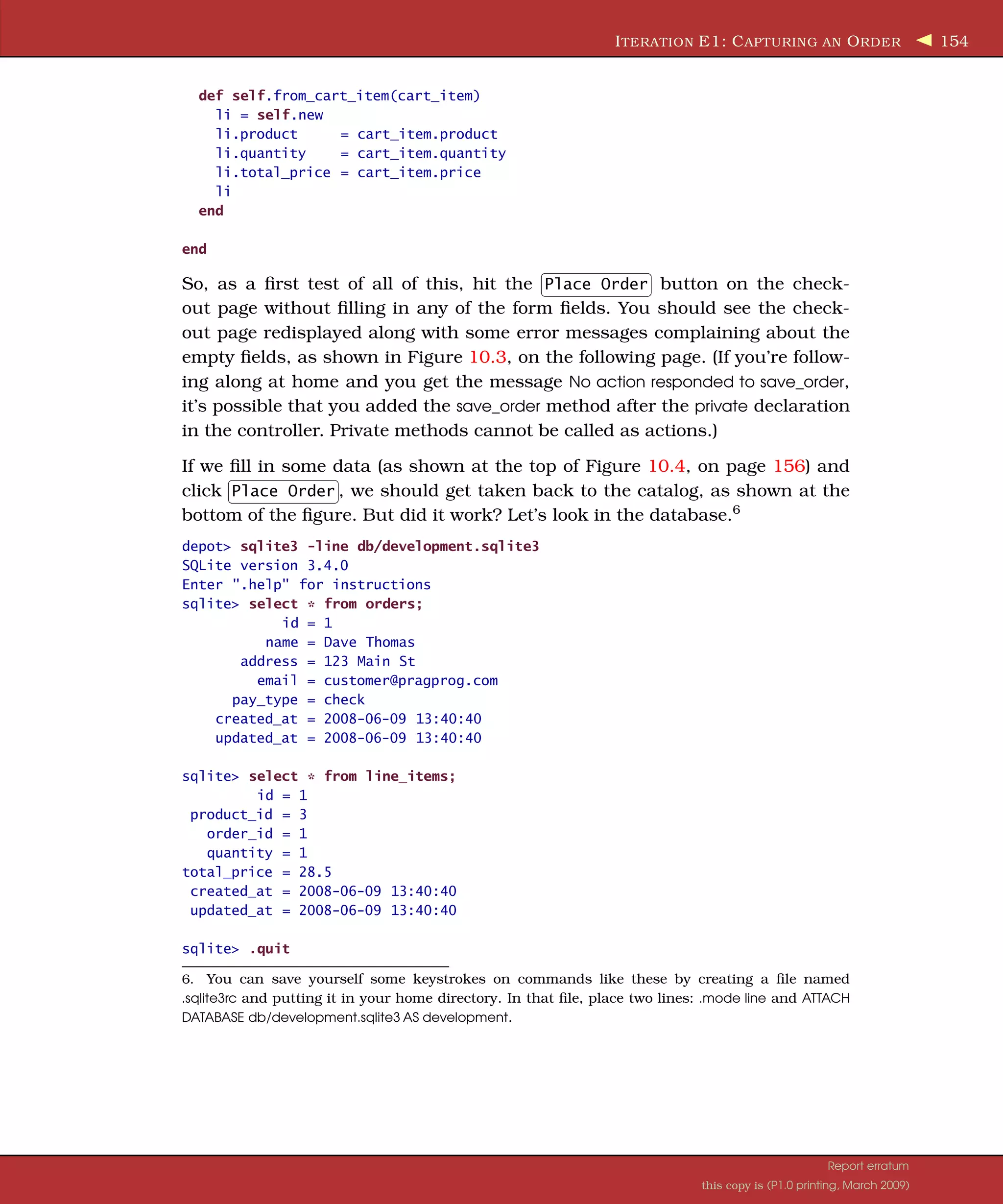

![I TERATION E1: C APTURING AN O RDER 155 Figure 10.3: Full house! Every field fails validation. One Last Ajax Change After we accept an order, we redirect to the index page, displaying the cheery flash message “Thank you for your order.” If the user continues to shop and they have JavaScript enabled in their browser, we’ll fill the cart in their side- bar without redrawing the main page. This means that the flash message will continue to be displayed. We’d rather it went away after we add the first item to the cart (as it does when JavaScript is disabled in the browser). Fortunately, the fix is simple: we just hide the <div> that contains the flash message when we add something to the cart. Except, nothing is really ever that simple. A first attempt to hide the flash might involve adding the following line to add_to_cart.js.rjs: page[:notice].hide # rest as before... However, this doesn’t work. If we come to the store for the first time, there’s nothing in the flash, so the <div> with an id of notice is not displayed. And, if there’s no <div> with the id of notice, the JavaScript generated by the RJS Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-155-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION E1: C APTURING AN O RDER 157 template that tries to hide it bombs out, and the rest of the template never gets run. As a result, you never see the cart update in the sidebar. The solution is a little hack. We want to run the .hide only if the notice <div> is present, but RJS doesn’t give us the ability to generate JavaScript that tests for <div>s. It does, however, let us iterate over elements on the page that match a certain CSS selector pattern. So let’s iterate over all <div> tags with an id of notice. The loop will find either one, which we can hide, or none, in which case the hide won’t get called. Download depot_p/app/views/store/add_to_cart.js.rjs page.select("div#notice" ).each { |div| div.hide } page.replace_html("cart" , :partial => "cart" , :object => @cart) page[:cart].visual_effect :blind_down if @cart.total_items == 1 page[:current_item].visual_effect :highlight, :startcolor => "#88ff88" , :endcolor => "#114411" The customer likes it. We’ve implemented product maintenance, a basic cata- log, and a shopping cart, and now we have a simple ordering system. Obviously we’ll also have to write some kind of fulfillment application, but that can wait for a new iteration. (And that iteration is one that we’ll skip in this book; it doesn’t have much new to say about Rails.) What We Just Did In a fairly short amount of time, we did the following: • We added orders and line_items tables (with the corresponding models) and linked them together. • We created a form to capture details for the order and linked it to the order model. • We added validation and used helper methods to display errors to the user. Playtime Here’s some stuff to try on your own: • Trace the flow through the methods save_order, add_line_items_from_cart, and from_cart_item. Do the controller, order model, and line item model seem suitably decoupled from each other? (One way to tell is to look at potential changes—if you change something, such as by adding a new Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-157-2048.jpg)

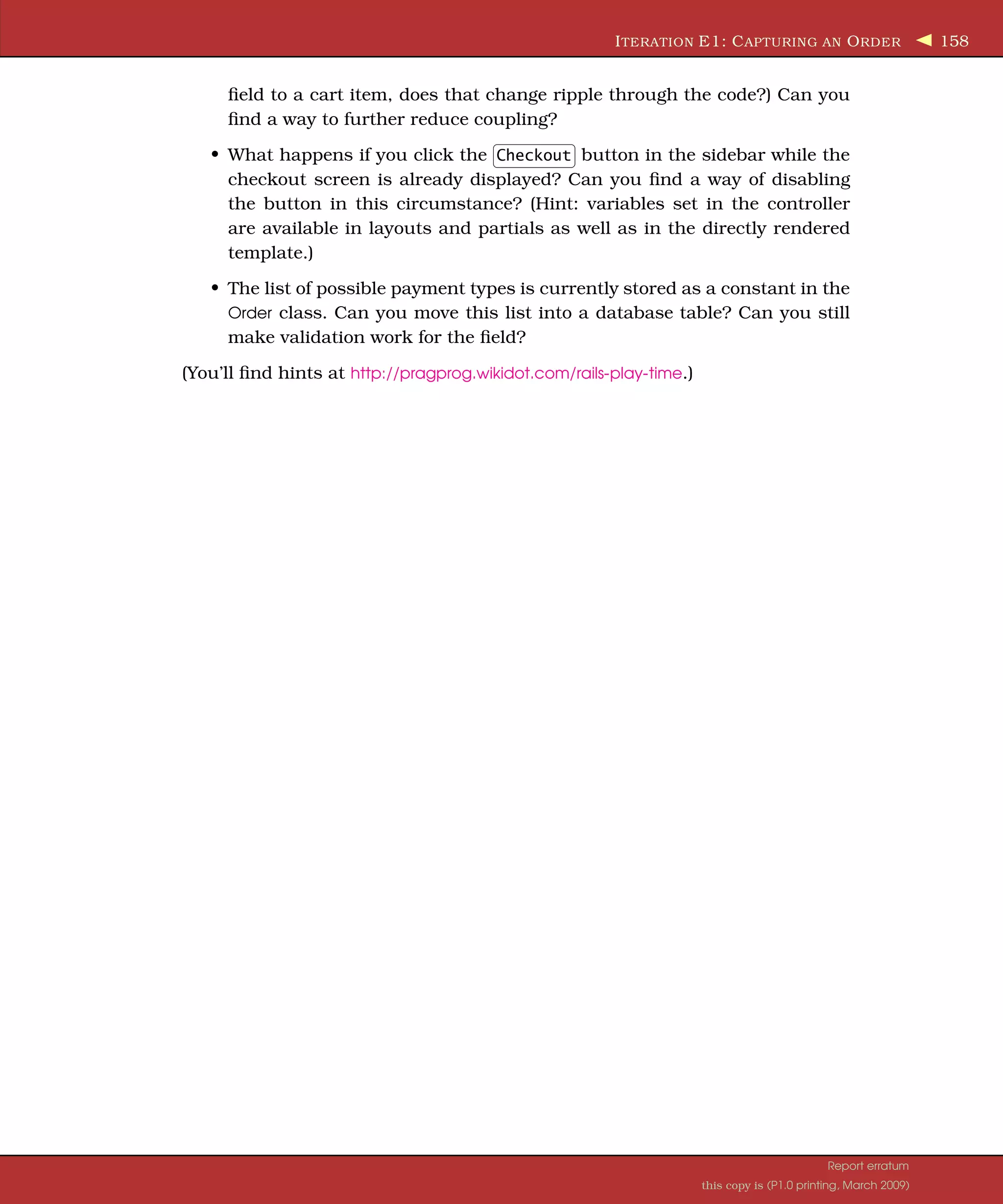

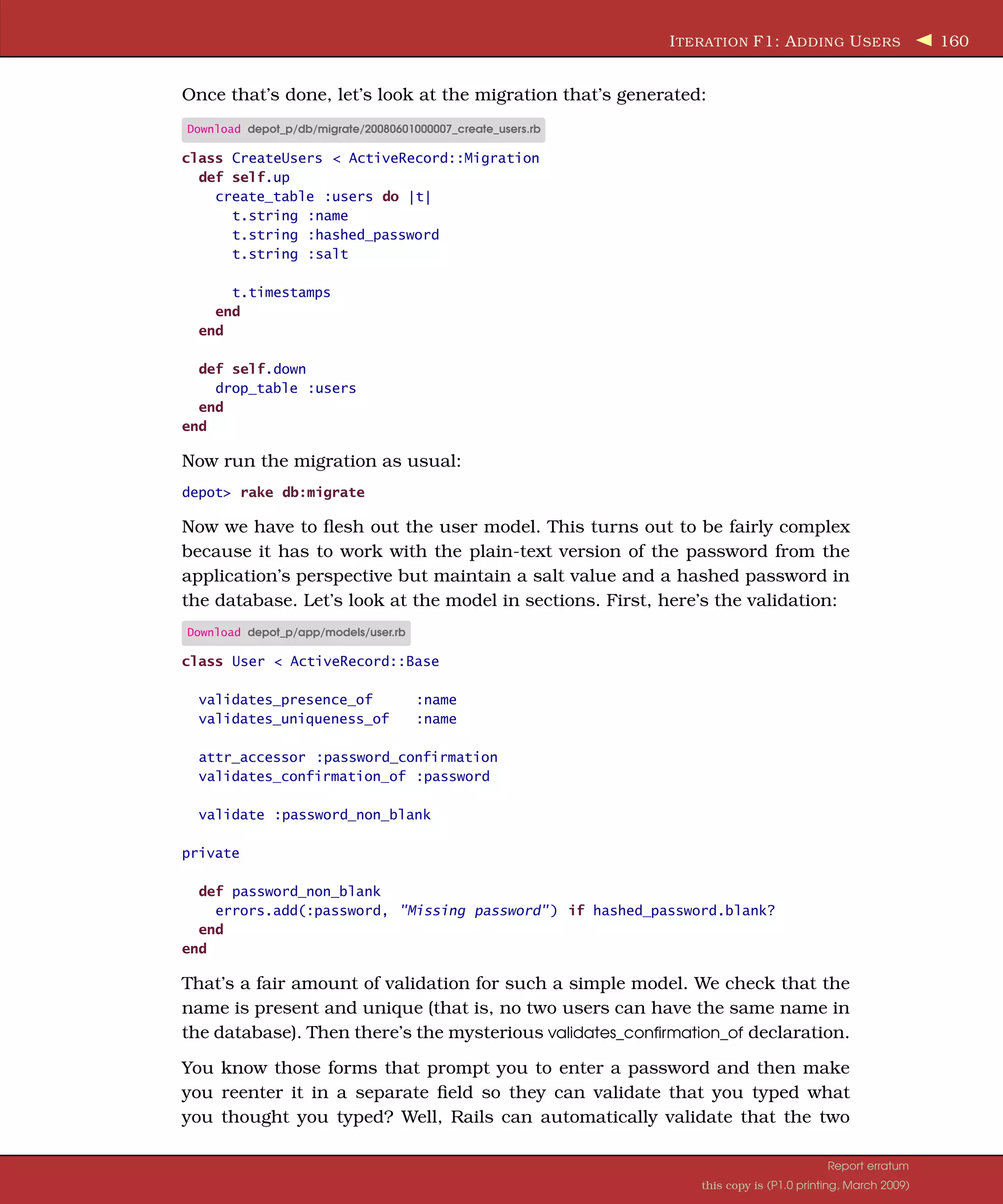

![In this chapter, we’ll see • adding virtual attributes to models, • using more validations, • coding forms without underlying models, • implementing one-action form handling, • adding authentication to a session, • using script/console, • using database transactions, and • writing an Active Record hook. Chapter 11 Task F: Administration We have a happy customer—in a very short time we’ve jointly put together a basic shopping cart that she can start showing to her users. There’s just one more change that she’d like to see. Right now, anyone can access the adminis- trative functions. She’d like us to add a basic user administration system that would force you to log in to get into the administration parts of the site. We’re happy to do that, because it gives us a chance to look at virtual attributes and filters, and it lets us tidy up the application somewhat. Chatting with our customer, it seems as if we don’t need a particularly sophis- ticated security system for our application. We just need to recognize a number of people based on usernames and passwords. Once recognized, these folks can use all of the administration functions. 11.1 Iteration F1: Adding Users Let’s start by creating a model and database table to hold our administrators’ usernames and passwords. Rather than store passwords in plain text, we’ll feed them through an SHA1 digest, resulting in a 160-bit hash. We check a user’s password by digesting the value they give us and comparing that hashed value with the one in the database. This system is made even more secure by salting the password, which varies the seed used when creating the hash by combining the password with a pseudorandom string.1 depot> ruby script/generate scaffold user name:string hashed_password:string salt:string Since this modified config/routes.rb, which is cached for performance reasons, you will need to restart your server. 1. For other recipes on how to do this, see the Authentication and Role-Based Authentication sec- tions in Chad Fowler’s Rails Recipes [Fow06].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-159-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION F1: A DDING U SERS 164 def create_new_salt self.salt = self.object_id.to_s + rand.to_s end def self.encrypted_password(password, salt) string_to_hash = password + "wibble" + salt Digest::SHA1.hexdigest(string_to_hash) end end Administering Our Users In addition to the model and table we set up, we already have some scaffold- ing generated to administer the model. However, this scaffolding needs some tweaks (mostly pruning) to be usable. Let’s start with the controller. It defines the standard methods: index, show, new, edit, update and delete. But in the case of users, there isn’t really much to show, except a name and an unintelligible password hash. So, let’s avoid the redirect to showing the user after either a create operation or an update operation. Instead, let’s redirect to the index and add the username to the flash notice. While we are here, let’s also order the users returned in the index by name: Download depot_p/app/controllers/users_controller.rb class UsersController < ApplicationController # GET /users # GET /users.xml def index @users = User.find(:all, :order => :name) respond_to do |format| format.html # index.html.erb format.xml { render :xml => @users } end end # GET /users/1 # GET /users/1.xml def show @user = User.find(params[:id]) respond_to do |format| format.html # show.html.erb format.xml { render :xml => @user } end end # GET /users/new # GET /users/new.xml def new @user = User.new Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-164-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION F1: A DDING U SERS 165 respond_to do |format| format.html # new.html.erb format.xml { render :xml => @user } end end # GET /users/1/edit def edit @user = User.find(params[:id]) end # POST /users # POST /users.xml def create @user = User.new(params[:user]) respond_to do |format| if @user.save flash[:notice] = "User #{@user.name} was successfully created." format.html { redirect_to(:action=>'index' ) } format.xml { render :xml => @user, :status => :created, :location => @user } else format.html { render :action => "new" } format.xml { render :xml => @user.errors, :status => :unprocessable_entity } end end end # PUT /users/1 # PUT /users/1.xml def update @user = User.find(params[:id]) respond_to do |format| if @user.update_attributes(params[:user]) flash[:notice] = "User #{@user.name} was successfully updated." format.html { redirect_to(:action=>'index' ) } format.xml { head :ok } else format.html { render :action => "edit" } format.xml { render :xml => @user.errors, :status => :unprocessable_entity } end end end # DELETE /users/1 # DELETE /users/1.xml def destroy @user = User.find(params[:id]) @user.destroy Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-165-2048.jpg)

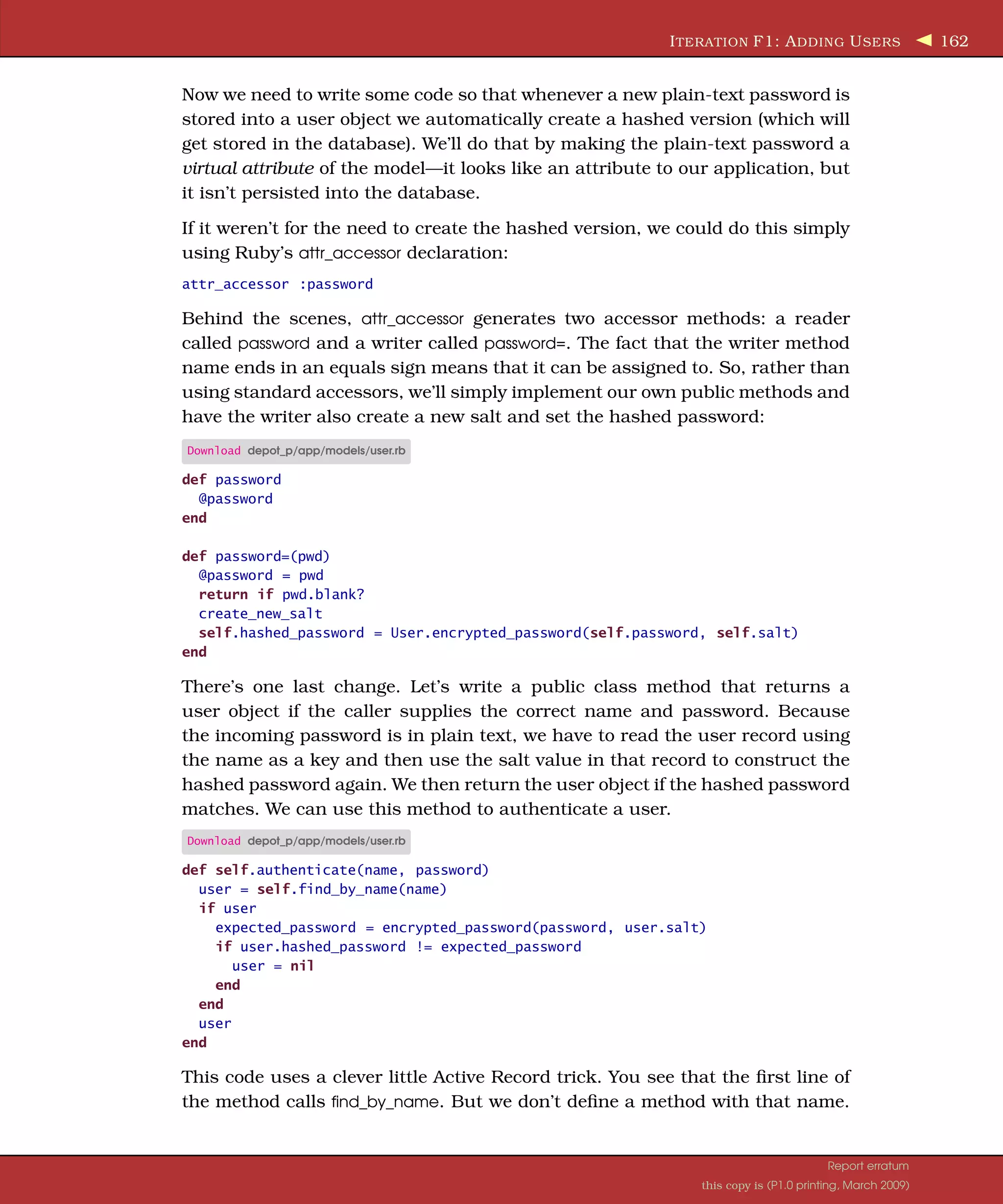

![I TERATION F2: L OGGING I N 168 If we look in our database, you’ll see that we’ve stored the user details. (Of course, the values in your row will be different, because the salt value is effec- tively random.) depot> sqlite3 -line db/development.sqlite3 "select * from users" id = 1 name = dave hashed_password = a12b1dbb97d3843ee27626b2bb96447941887ded salt = 203333500.653238054564258 created_at = 2008-05-19 21:40:19 updated_at = 2008-05-19 21:40:19 11.2 Iteration F2: Logging In What does it mean to add login support for administrators of our store? • We need to provide a form that allows them to enter their username and password. • Once they are logged in, we need to record that fact somehow for the rest of their session (or until they log out). • We need to restrict access to the administrative parts of the application, allowing only people who are logged in to administer the store. We’ll need a controller to support a login action, and it will need to record something in session to say that an administrator is logged in. Let’s start by defining an admin controller with three actions, login, logout, and index (which simply welcomes administrators): depot> ruby script/generate controller admin login logout index exists app/controllers/ exists app/helpers/ create app/views/admin exists test/functional/ create app/controllers/admin_controller.rb create test/functional/admin_controller_test.rb create app/helpers/admin_helper.rbs create app/views/admin/login.html.erb create app/views/admin/logout.html.erb create app/views/admin/index.html.erb The login action will need to record something in session to say that an admin- istrator is logged in. Let’s have it store the id of their User object using the key :user_id. The login code looks like this: Download depot_p/app/controllers/admin_controller.rb def login if request.post? user = User.authenticate(params[:name], params[:password]) if user session[:user_id] = user.id Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-168-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION F2: L OGGING I N 169 redirect_to(:action => "index" ) else flash.now[:notice] = "Invalid user/password combination" end end end Inside this method we’ll detect whether we’re being called to display the ini- tial (empty) form or whether we’re being called to save away the data in a completed form. We’ll do this by looking at the HTTP method of the incoming request. If it comes from an <a href="..."> link, we’ll see it as a GET request. If instead it contains form data (which it will when the user hits the submit but- ton), we’ll see a POST. (For this reason, this style is sometimes called postback handling.) With postback handling, there is no need to issue a redirect and therefore no need to make flash available across requests. flash.now makes the notice available to the template without storing it in the session. We are also doing something else new, namely, using a form that isn’t directly associated with a model object. To see how that works, let’s look at the tem- plate for the login action: Download depot_p/app/views/admin/login.html.erb <div class="depot-form"> <% form_tag do %> <fieldset> <legend>Please Log In</legend> <div> <label for="name">Name:</label> <%= text_field_tag :name, params[:name] %> </div> <div> <label for="password">Password:</label> <%= password_field_tag :password, params[:password] %> </div> <div> <%= submit_tag "Login" %> </div> </fieldset> <% end %> </div> This form is different from ones we saw earlier. Rather than using form_for, it uses form_tag, which simply builds a regular HTML <form>. Inside that form, it uses text_field_tag and password_field_tag, two helpers that create HTML <input> tags. Each helper takes two parameters. The first is the name to give Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-169-2048.jpg)

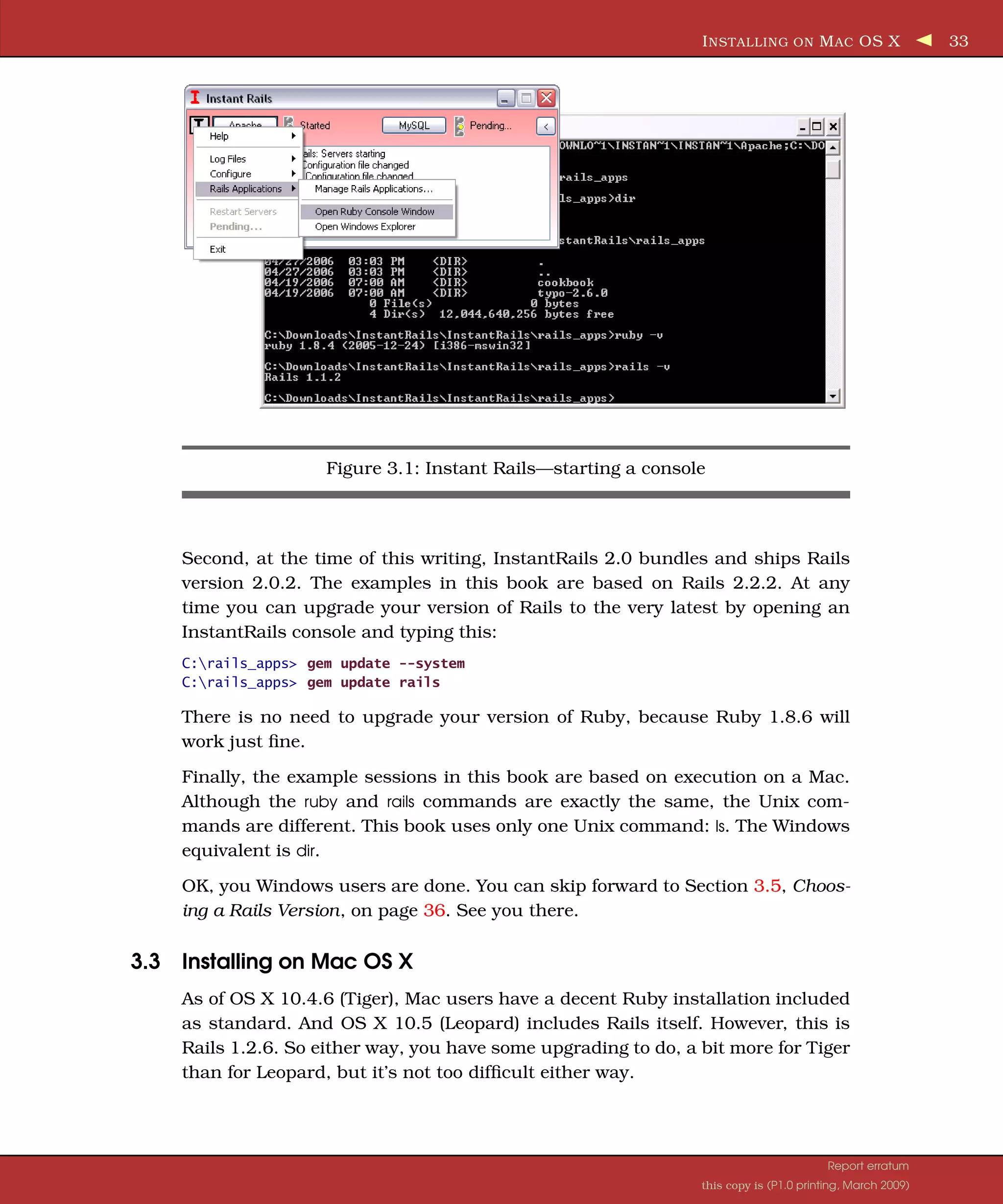

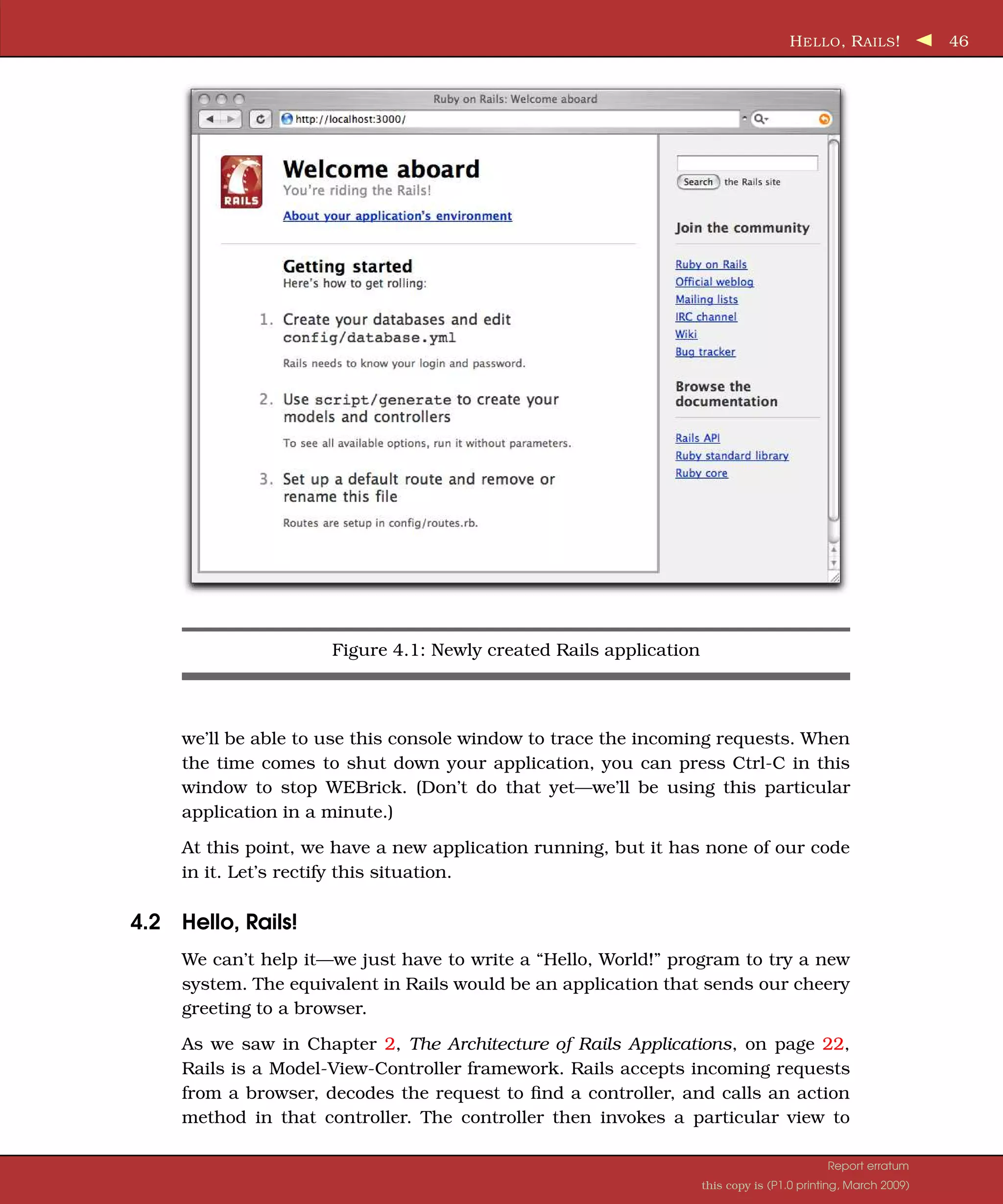

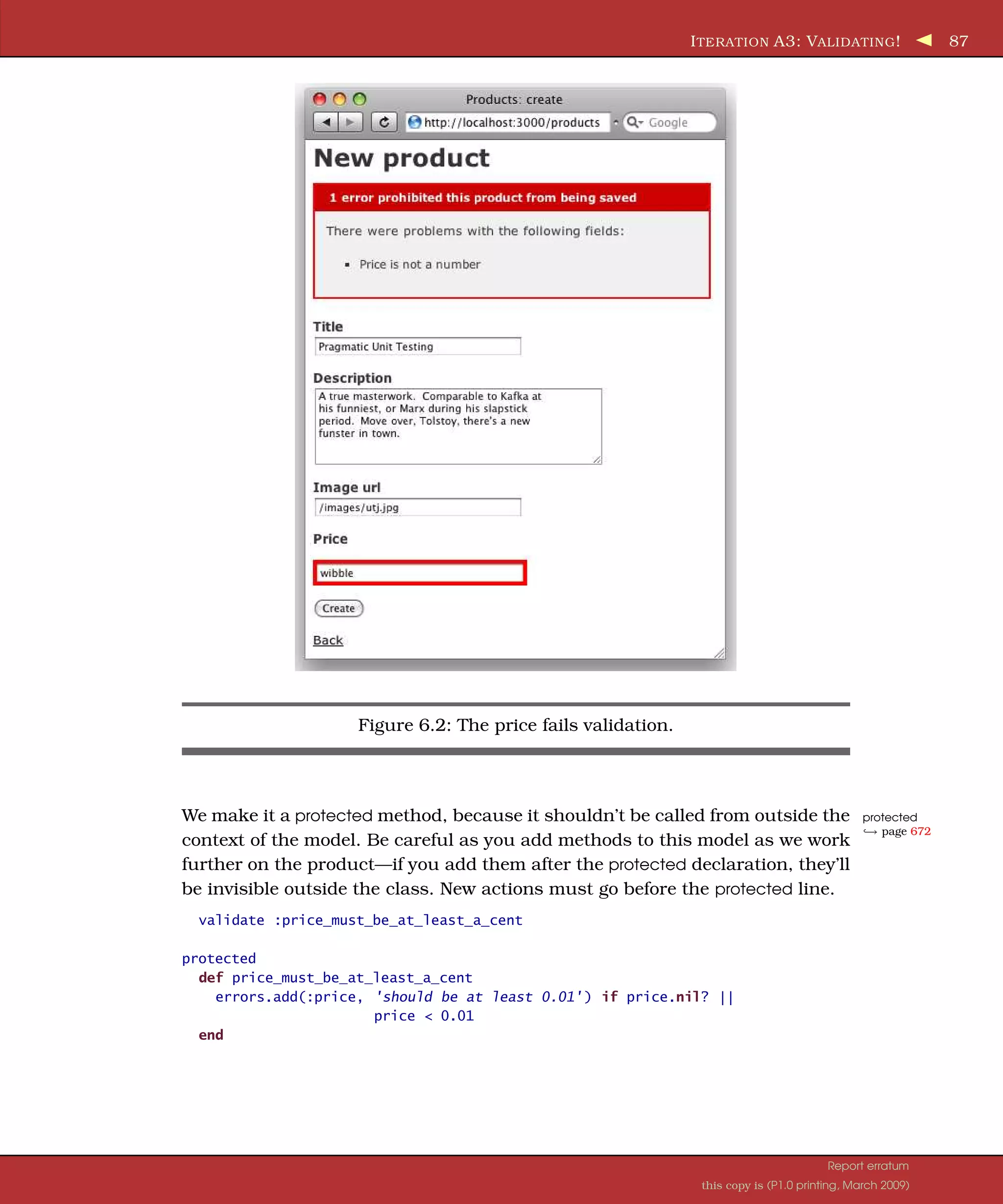

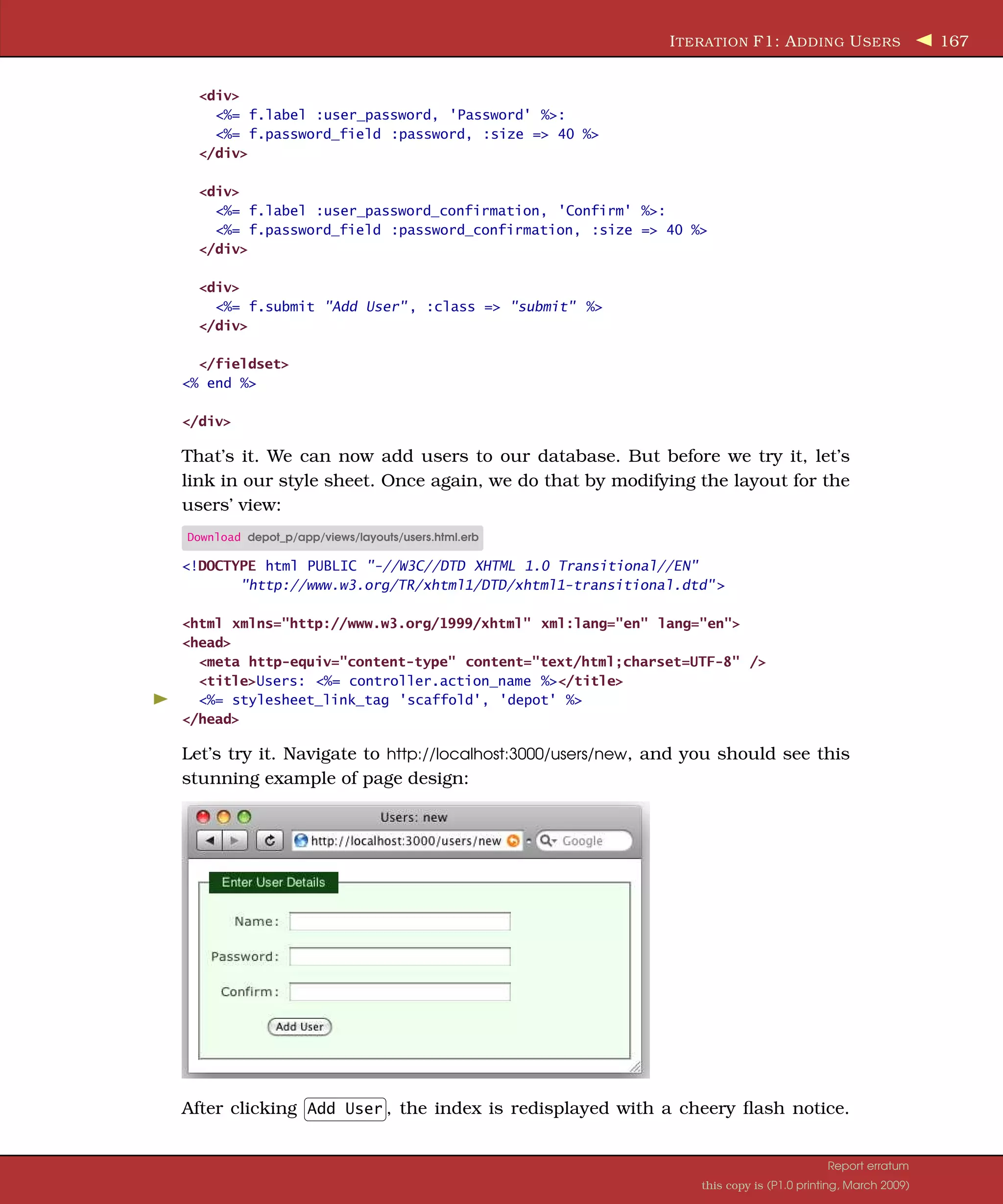

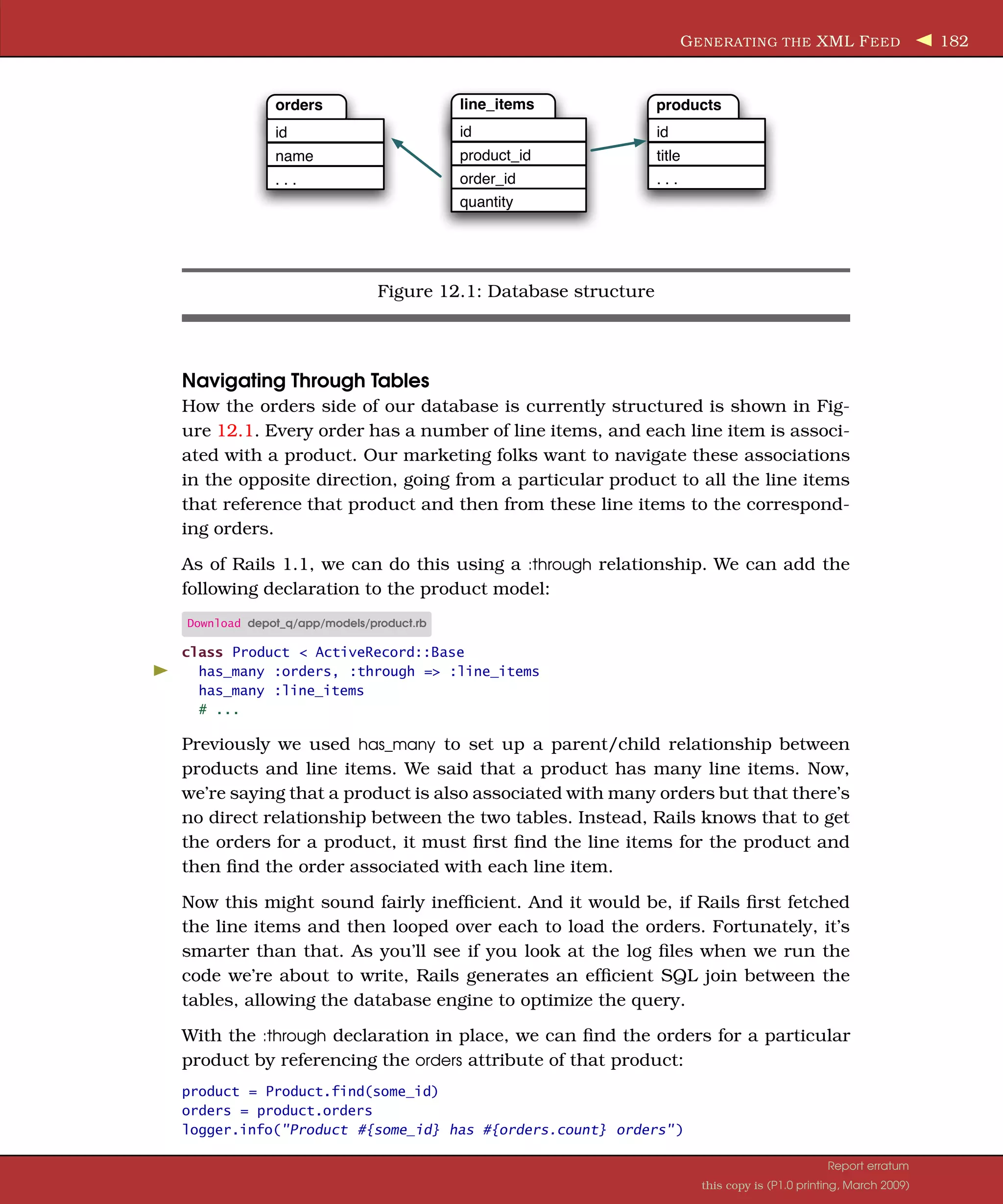

![I TERATION F2: L OGGING I N 170 Template <% form_tag do %> Name: <%= text_field_tag :name, params[:name] %> ... <% end %> Controller def login name = params[:name] ... end Figure 11.1: Parameters flow between controllers, templates, and browsers. to the field, and the second is the value with which to populate the field. This style of form allows us to associate values in the params structure directly with form fields—no model object is required. In our case, we chose to use the params object directly in the form. An alternative would be to have the controller set instance variables. The flow for this style of form is illustrated in Figure 11.1. Note how the value of the form field is communicated between the controller and the view using the params hash: the view gets the value to display in the field from params[:name], and when the user submits the form, the new field value is made available to the controller the same way. If the user successfully logs in, we store the id of the user record in the session data. We’ll use the presence of that value in the session as a flag to indicate that an admin user is logged in. Finally, it’s about time to add the index page, the first screen that administra- tors see when they log in. Let’s make it useful—we’ll have it display the total number of orders in our store. Create the template in the file index.html.erb in the directory app/views/admin. (This template uses the pluralize helper, which in Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-170-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION F3: L IMITING A CCESS 171 this case generates the string order or orders depending on the cardinality of its first parameter.) Download depot_p/app/views/admin/index.html.erb <h1>Welcome</h1> It's <%= Time.now %> We have <%= pluralize(@total_orders, "order" ) %>. The index action sets up the count: Download depot_p/app/controllers/admin_controller.rb def index @total_orders = Order.count end Now we can experience the joy of logging in as an administrator: We show our customer where we are, but she points out that we still haven’t controlled access to the administrative pages (which was, after all, the point of this exercise). 11.3 Iteration F3: Limiting Access We want to prevent people without an administrative login from accessing our site’s admin pages. It turns out that it’s easy to implement using the Rails filter facility. Rails filters allow you to intercept calls to action methods, adding your own processing before they are invoked, after they return, or both. In our case, we’ll use a before filter to intercept all calls to the actions in our admin controller. The interceptor can check session[:user_id]. If set and if it corresponds to a user in the database, the application knows an administrator is logged in, and the Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-171-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION F3: L IMITING A CCESS 172 call can proceed. If it’s not set, the interceptor can issue a redirect, in this case to our login page. Where should we put this method? It could sit directly in the admin controller, but, for reasons that will become apparent shortly, let’s put it instead in Appli- cationController, the parent class of all our controllers. This is in the file applica- tion.rb3 in the directory app/controllers. Note too that we need to restrict access to this method, because the methods in application.rb appear as instance meth- ods in all our controllers. Any public methods here are exposed to end users as actions. Download depot_p/app/controllers/application.rb # Filters added to this controller apply to all controllers in the application. # Likewise, all the methods added will be available for all controllers. class ApplicationController < ActionController::Base before_filter :authorize, :except => :login helper :all # include all helpers, all the time # See ActionController::RequestForgeryProtection for details # Uncomment the :secret if you're not using the cookie session store protect_from_forgery :secret => '8fc080370e56e929a2d5afca5540a0f7' # See ActionController::Base for details # Uncomment this to filter the contents of submitted sensitive data parameters # from your application log (in this case, all fields with names like "password"). # filter_parameter_logging :password protected def authorize unless User.find_by_id(session[:user_id]) flash[:notice] = "Please log in" redirect_to :controller => 'admin' , :action => 'login' end end end This authorization method can be invoked before any actions in our adminis- tration controller by adding just one line. Note that we do this for all methods in all controllers, with the exception of methods named login, of which there should be only one, namely, in the Admin controller. Note that this is going too far. We have just limited access to the store itself to administrators. That’s not good. We could go back and change things so that we mark only those methods that specifically need authorization. Such an approach is called blacklisting and is prone to errors of omission. A much better approach is to “whitelist” or list methods or controllers for which authorization is not required, as we did for 3. Starting with Rails 2.3, this file will be named application_controller.rb. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-172-2048.jpg)

![I TERATION F3: L IMITING A CCESS 173 A Friendlier Login System As the code stands now, if an administrator tries to access a restricted page before they are logged in, they are taken to the login page. When they then log in, the standard status page is displayed—their original request is forgotten. If you want, you can change the application to forward them to their originally requested page once they log in. First, in the authorize method, remember the incoming request’s URI in the ses- sion if you need to log the user in: def authorize unless User.find_by_id(session[:user_id]) session[:original_uri] = request.request_uri flash[:notice] = "Please log in" redirect_to(:controller => "admin" , :action => "login" ) end end Once we log someone in, we can then check to see whether there’s a URI stored in the session and redirect to it if so. We also need to clear that stored URI once used. def login session[:user_id] = nil if request.post? user = User.authenticate(params[:name], params[:password]) if user session[:user_id] = user.id uri = session[:original_uri] session[:original_uri] = nil redirect_to(uri || { :action => "index" }) else flash.now[:notice] = "Invalid user/password combination" end end end the login method. We do this simply by providing an override for the authorize method within the StoreController class: Download depot_q/app/controllers/store_controller.rb class StoreController < ApplicationController #... protected def authorize end end Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-173-2048.jpg)

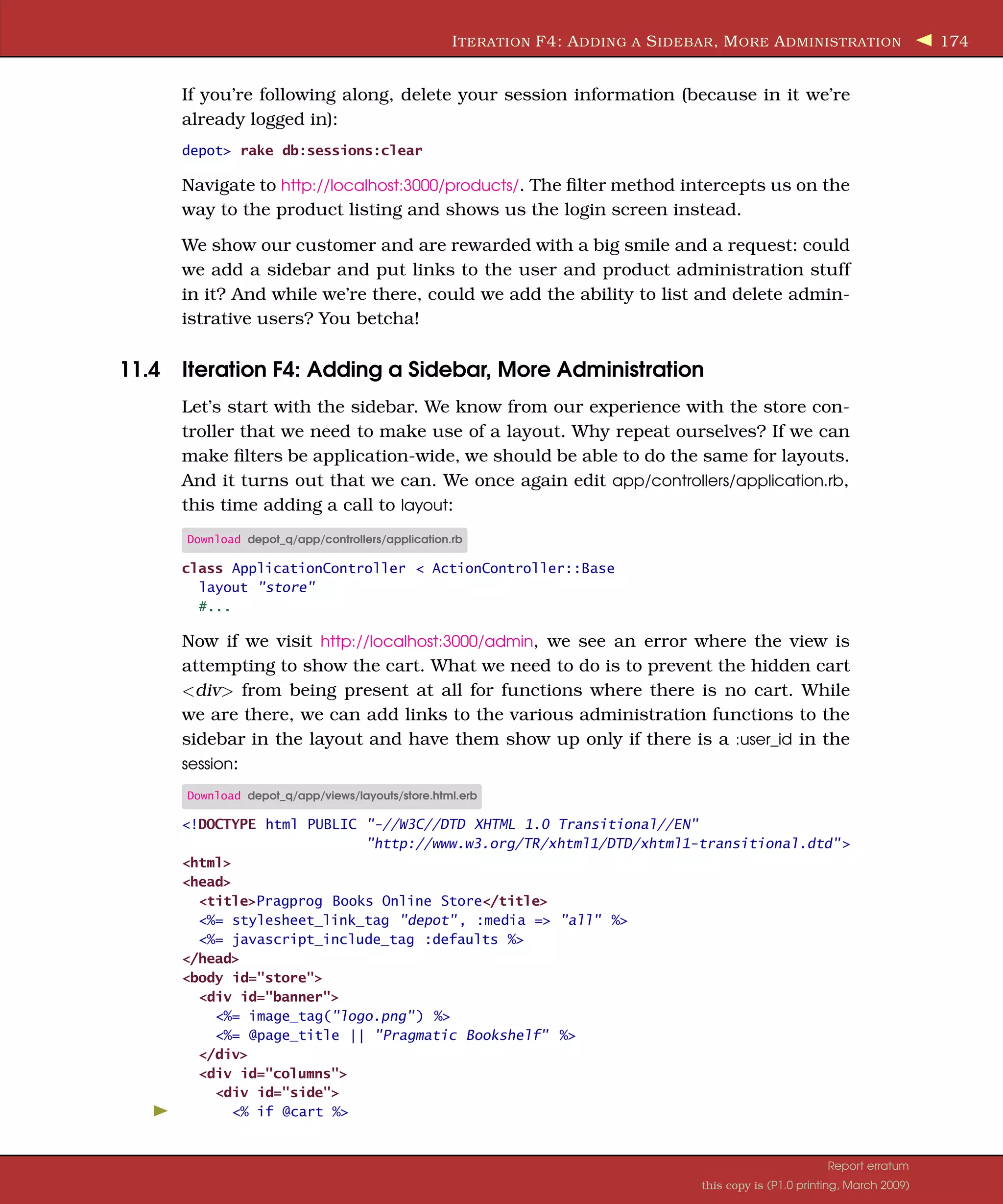

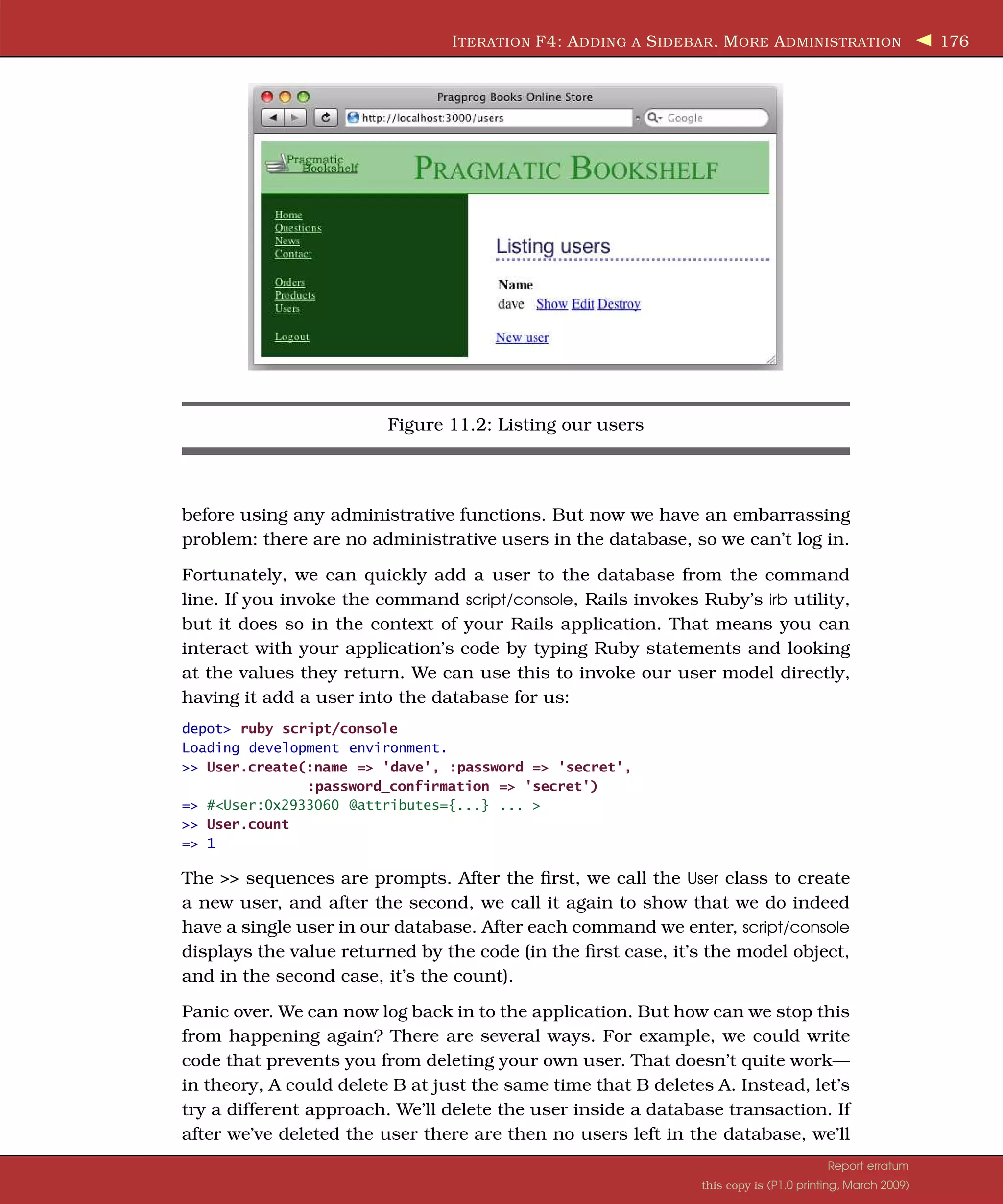

![I TERATION F4: A DDING A S IDEBAR , M ORE A DMINISTRATION 175 <% hidden_div_if(@cart.items.empty?, :id => "cart" ) do %> <%= render(:partial => "cart" , :object => @cart) %> <% end %> <% end %> <a href="http://www....">Home</a><br /> <a href="http://www..../faq">Questions</a><br /> <a href="http://www..../news">News</a><br /> <a href="http://www..../contact">Contact</a><br /> <% if session[:user_id] %> <br /> <%= link_to 'Orders', :controller => 'orders' %><br /> <%= link_to 'Products', :controller => 'products' %><br /> <%= link_to 'Users', :controller => 'users' %><br /> <br /> <%= link_to 'Logout', :controller => 'admin', :action => 'logout' %> <% end %> </div> <div id="main"> <% if flash[:notice] -%> <div id="notice"><%= flash[:notice] %></div> <% end -%> <%= yield :layout %> </div> </div> </body> </html> Now if we return to http://localhost:3000/admin, we see the familiar Pragmatic Bookshelf banner and sidebar. But if we visit http://localhost:3000/users, we do not. It turns out that there is one more thing that we need to do: we need to stop the generated scaffolding from overriding the application default layout. And nothing could be easier. We simply remove the generated layouts:4 rm app/views/layouts/products.html.erb rm app/views/layouts/users.html.erb rm app/views/layouts/orders.html.erb Would the Last Admin to Leave... Now it is all starting to come together. We can log in, and by clicking a link on the sidebar, we can see a list of users. Let’s play with this. We bring up the user list screen that looks something like Figure 11.2, on the next page; then we click the destroy link next to dave to delete that user. Sure enough, our user is removed. But to our surprise, we’re then presented with the login screen instead. We just deleted the only admin- istrative user from the system. When the next request came in, the authenti- cation failed, so the application refused to let us in. We have to log in again 4. Windows users should use the erase command instead. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-175-2048.jpg)

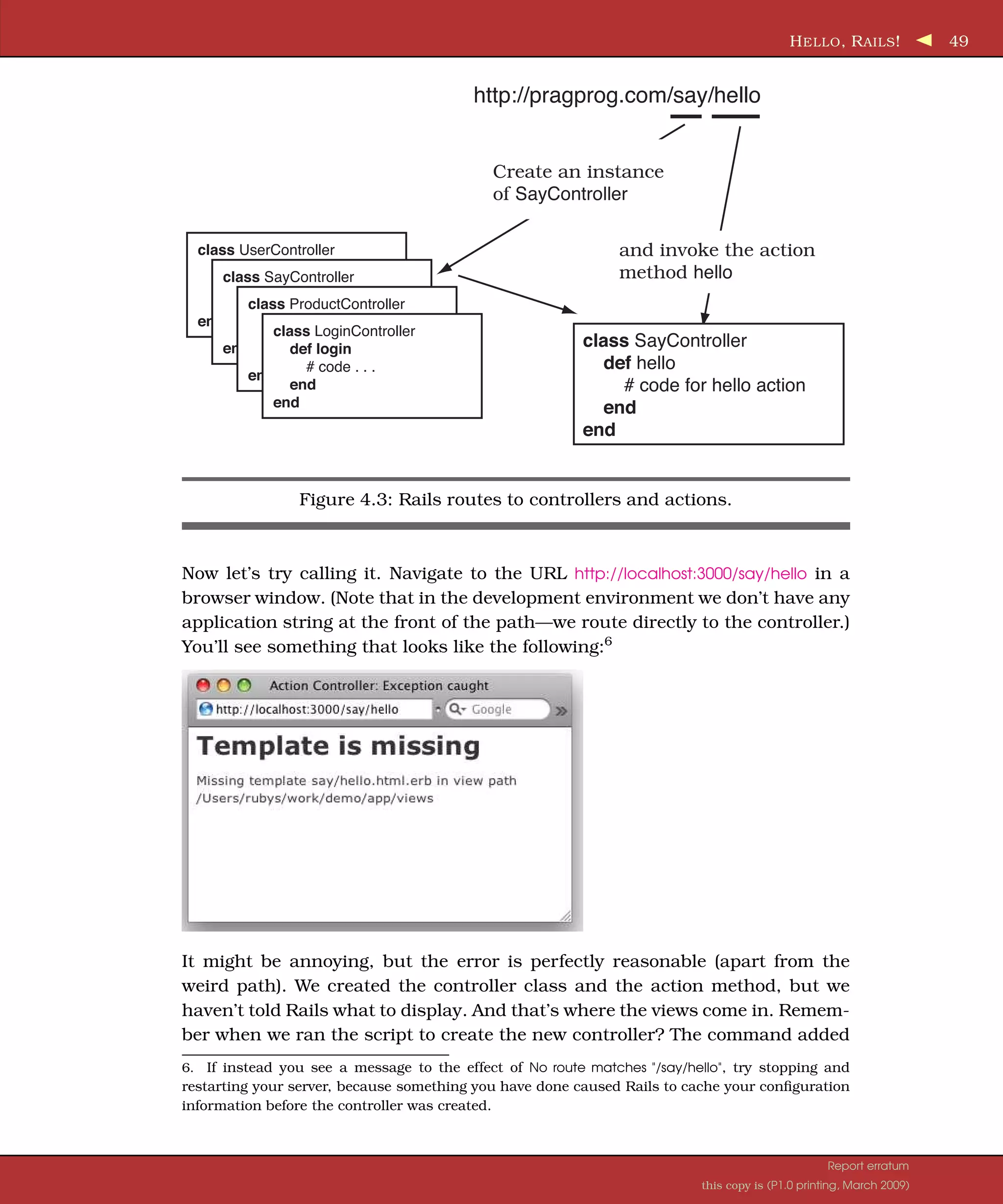

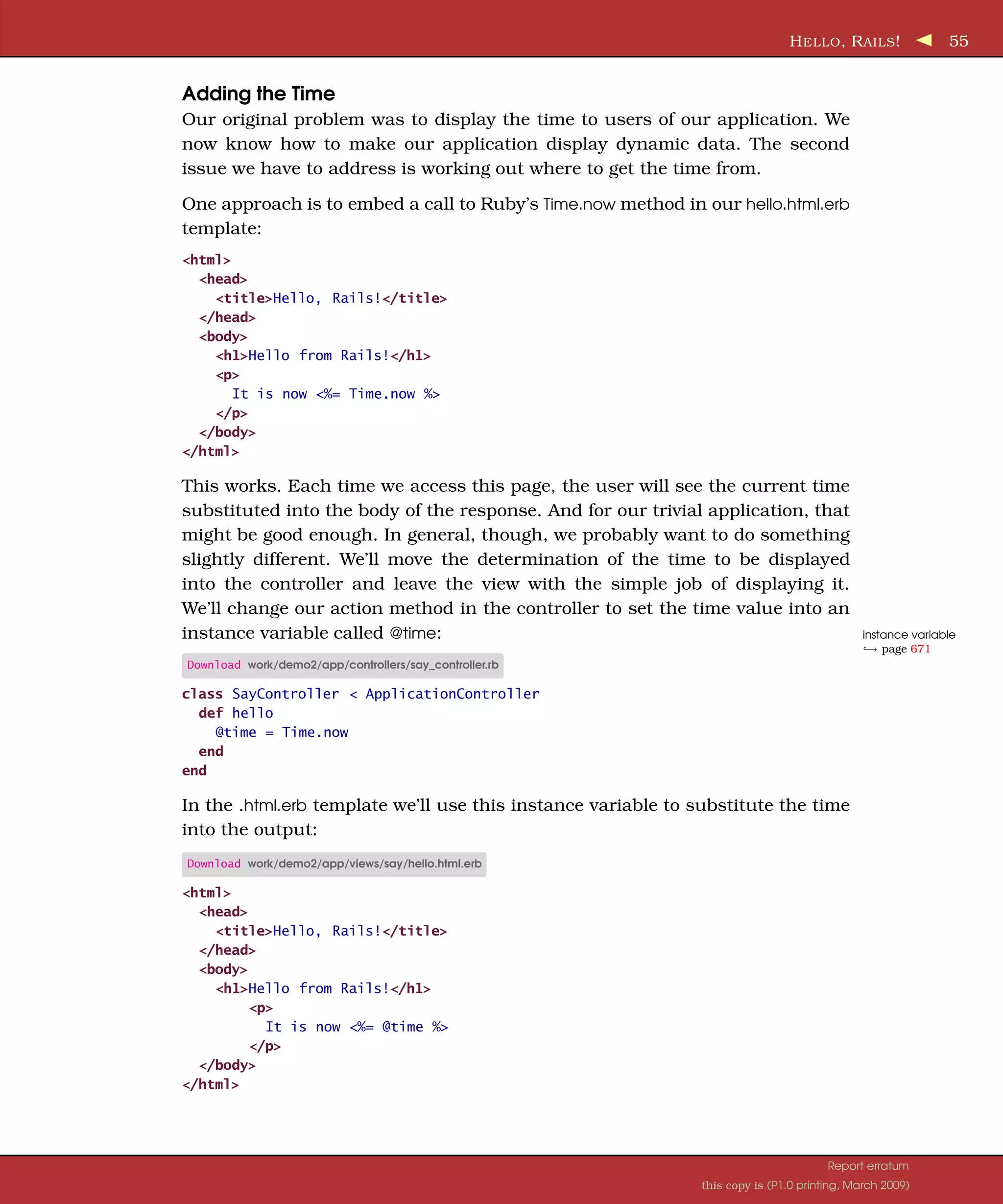

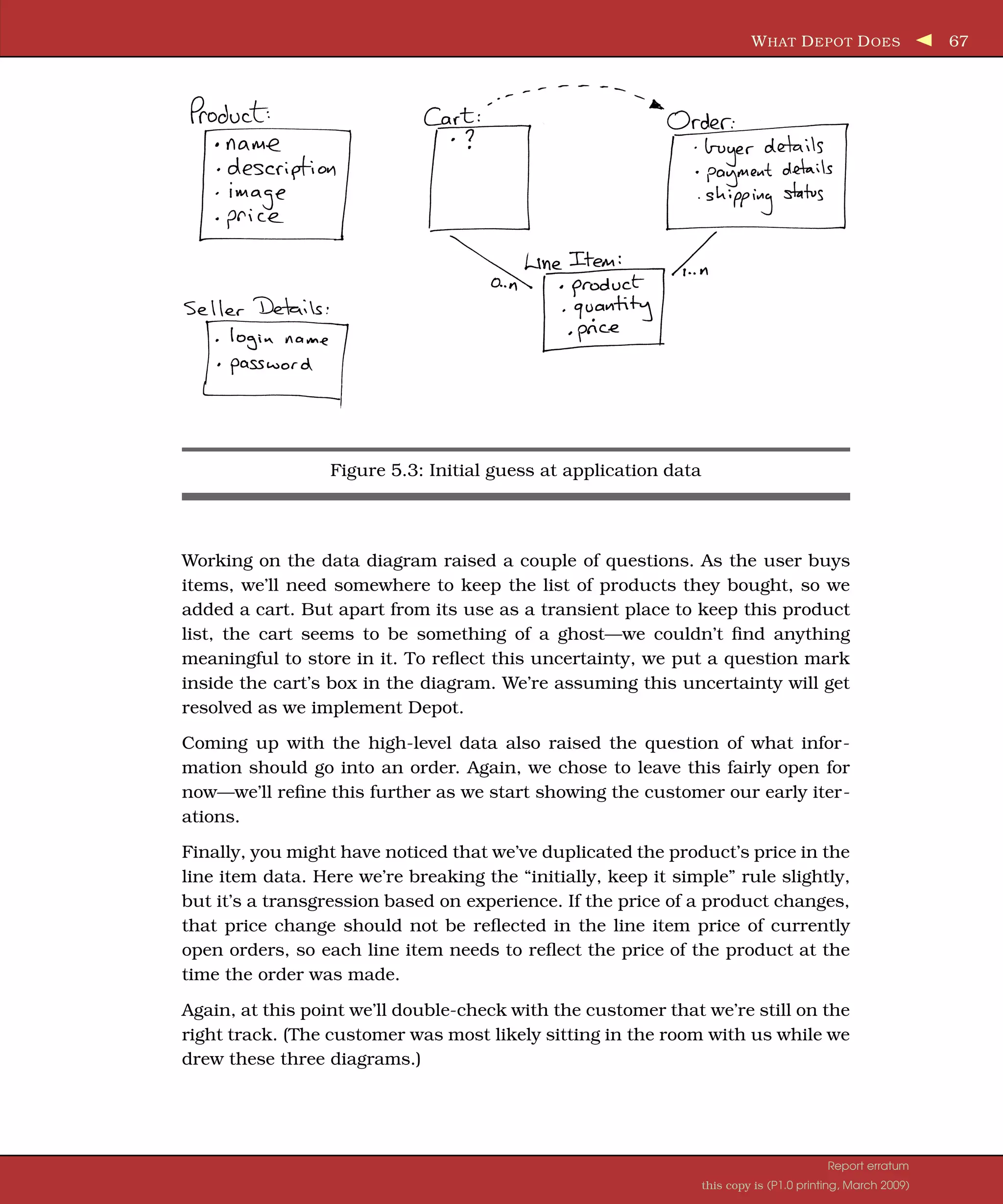

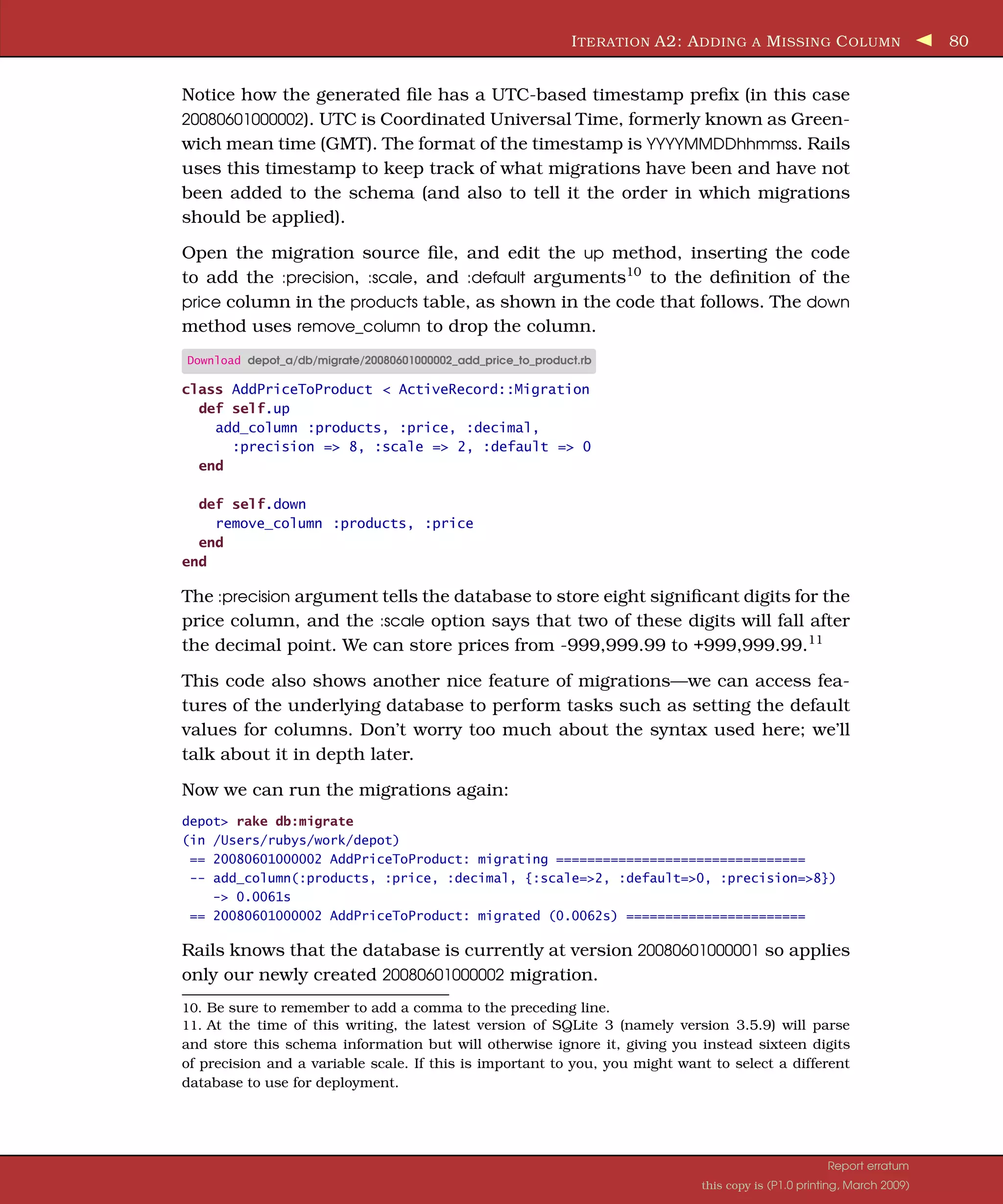

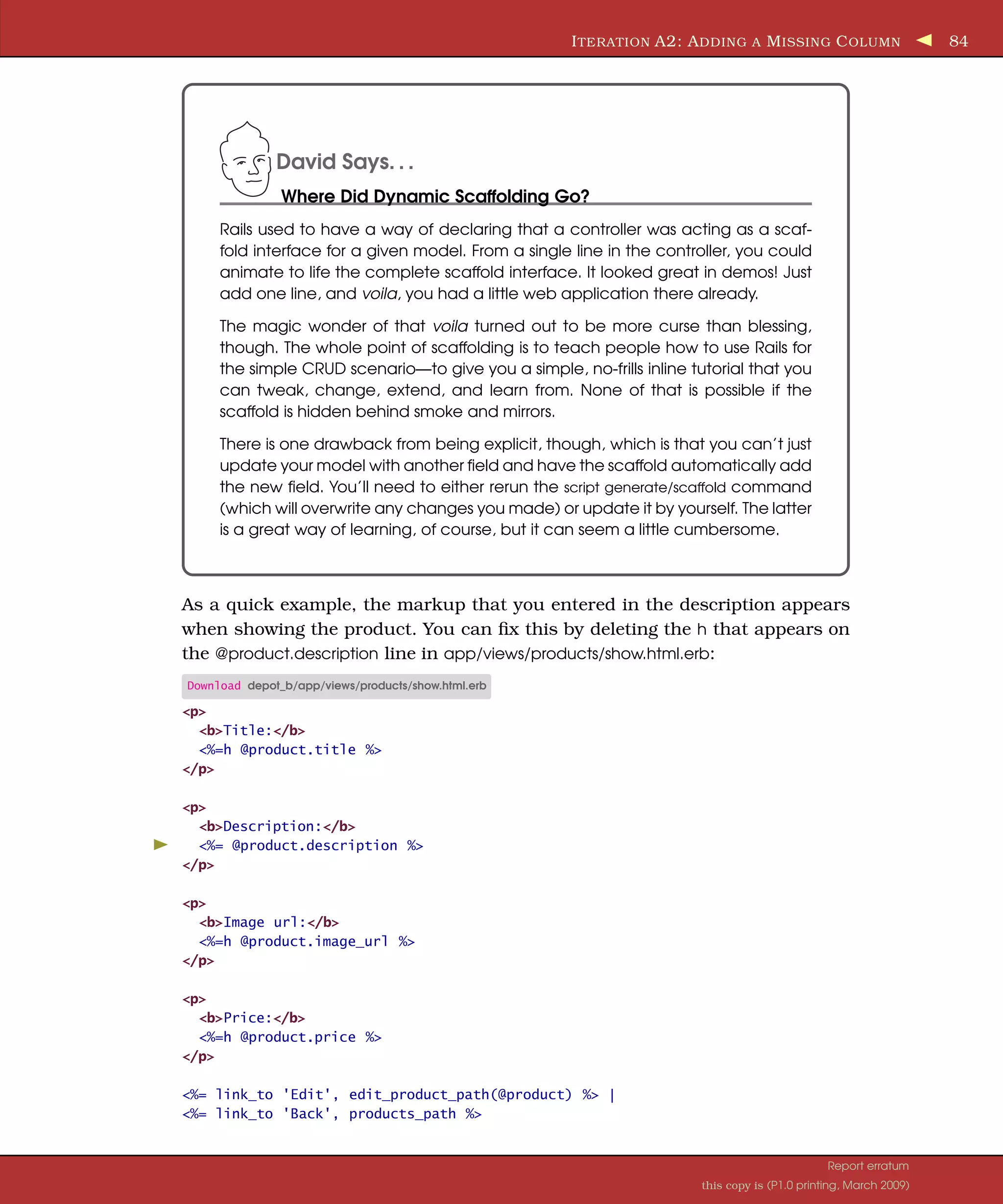

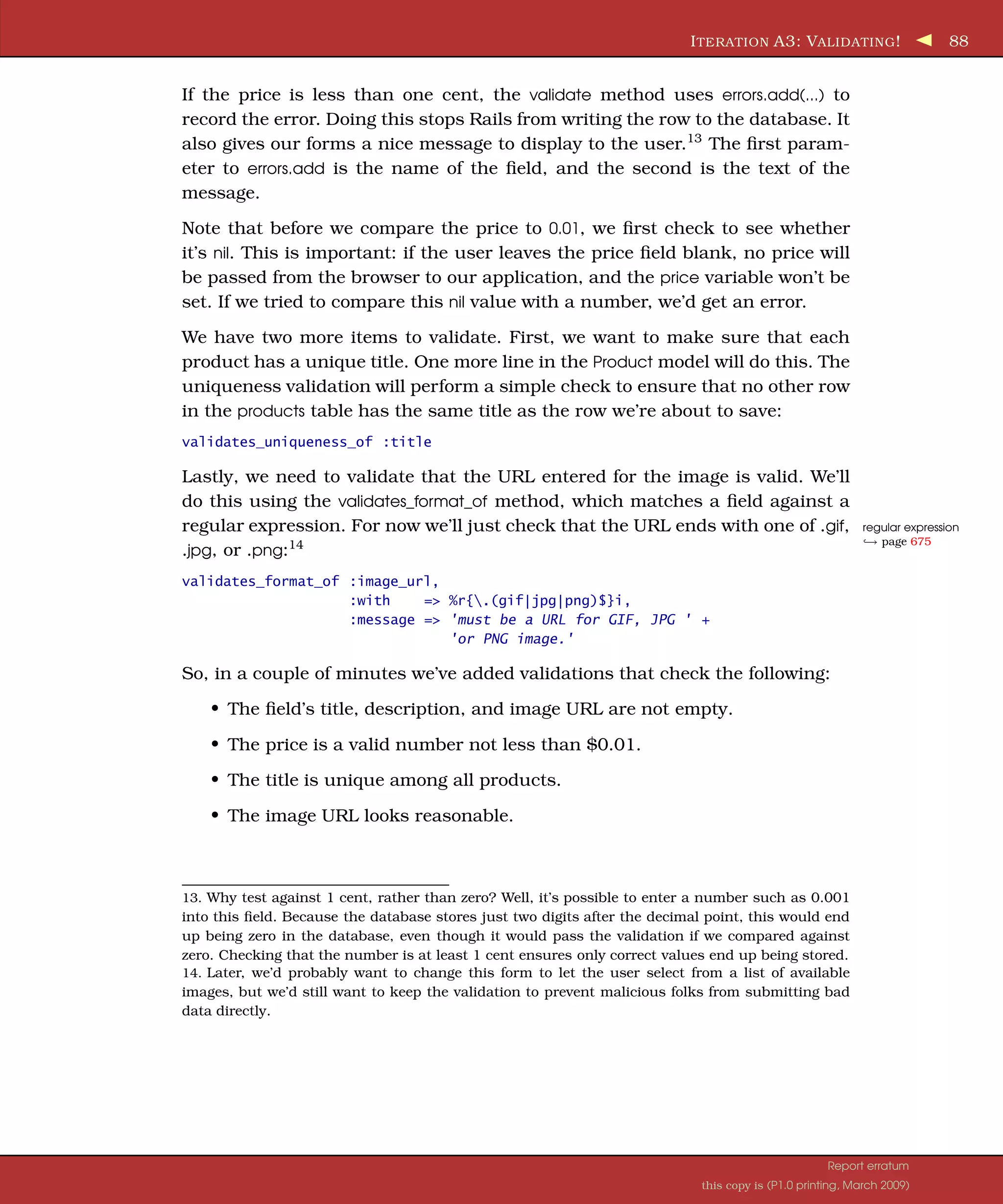

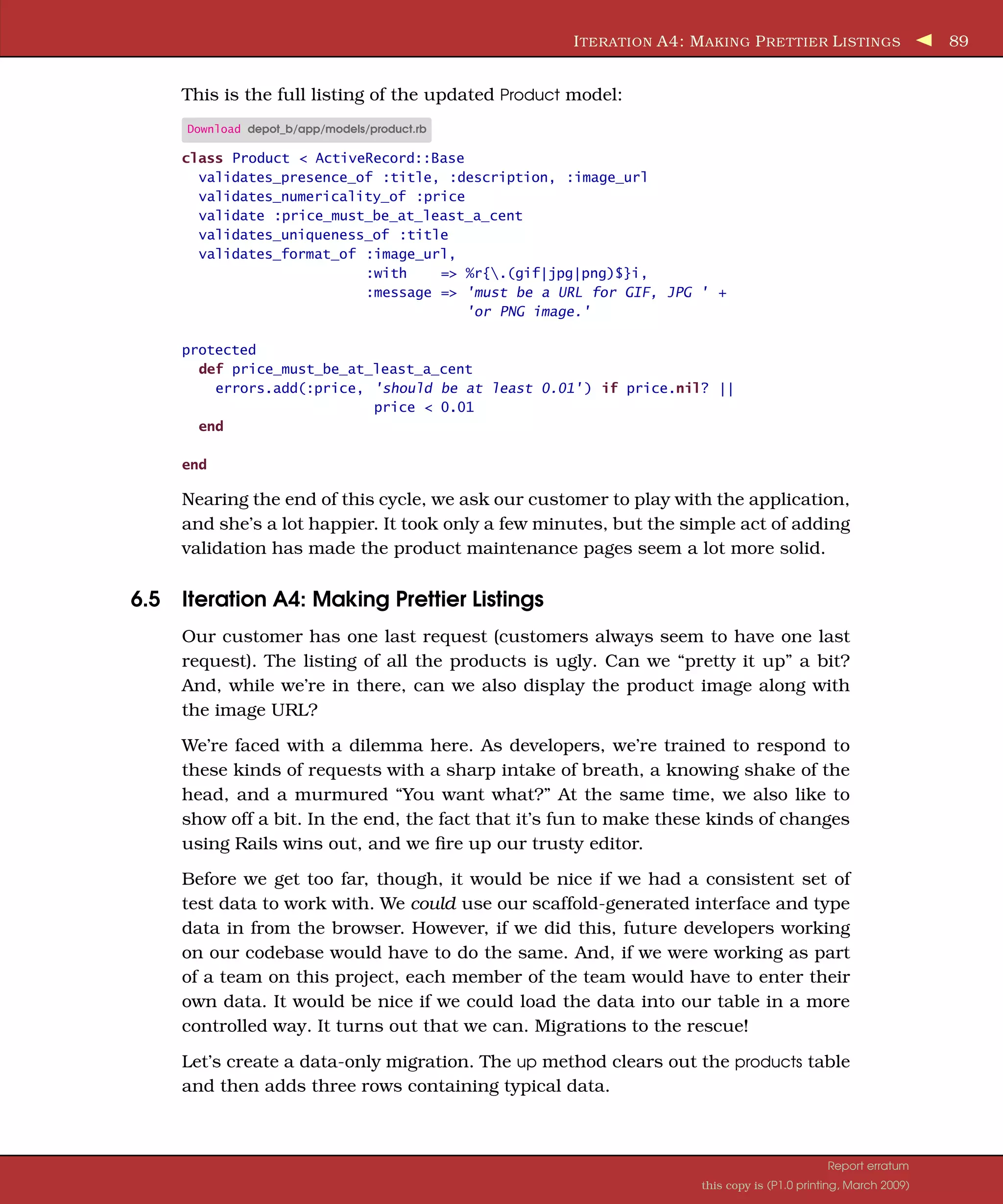

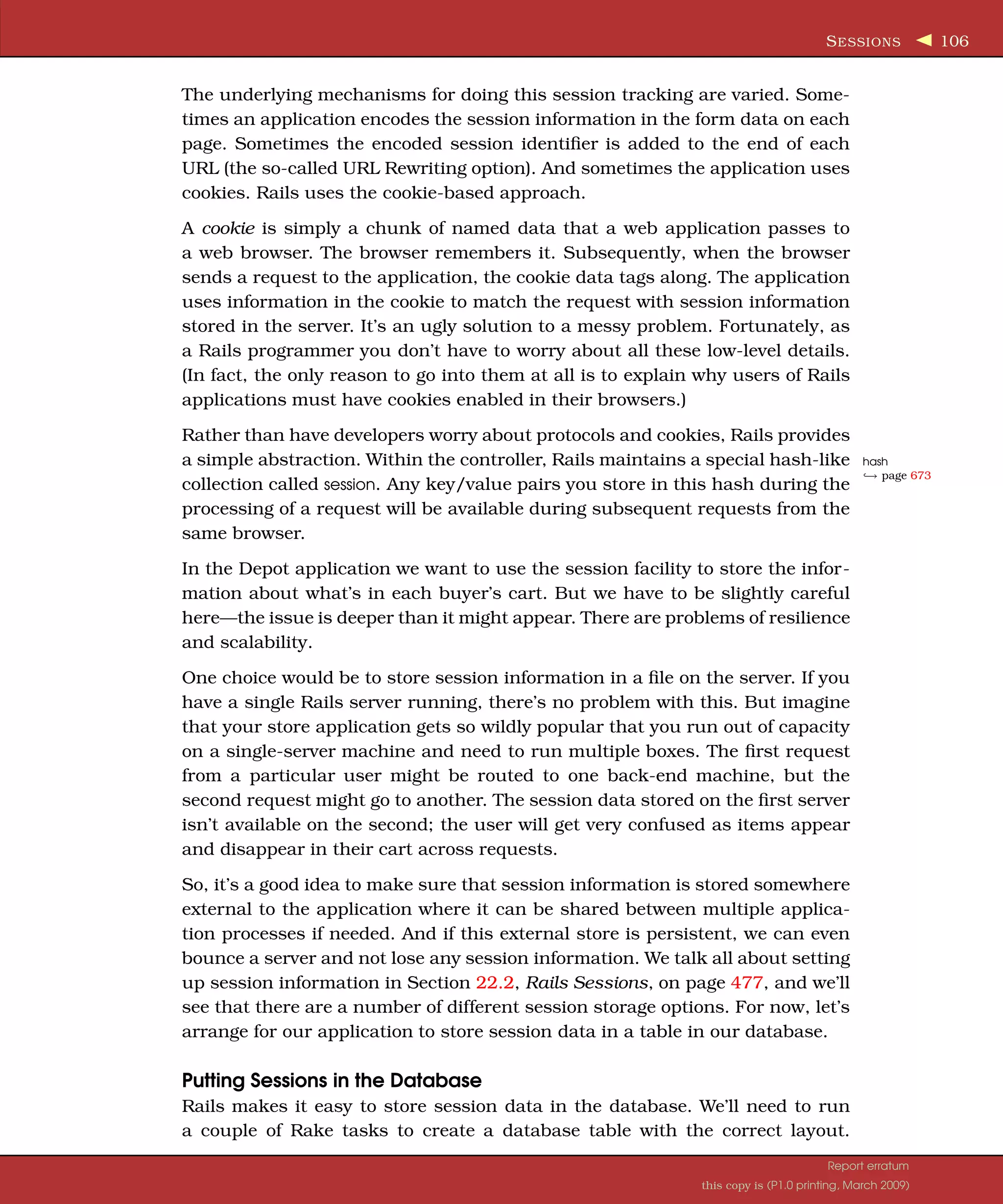

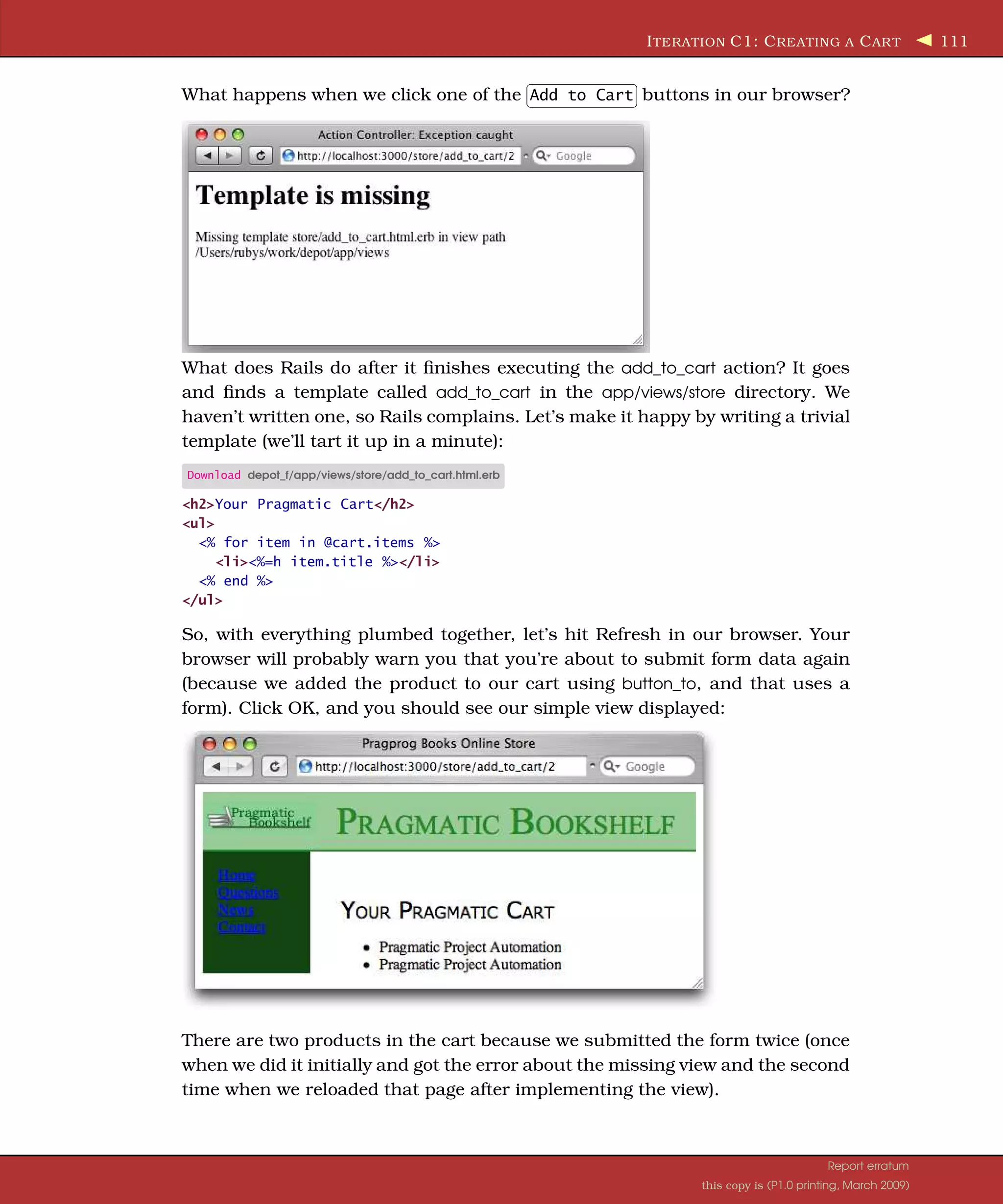

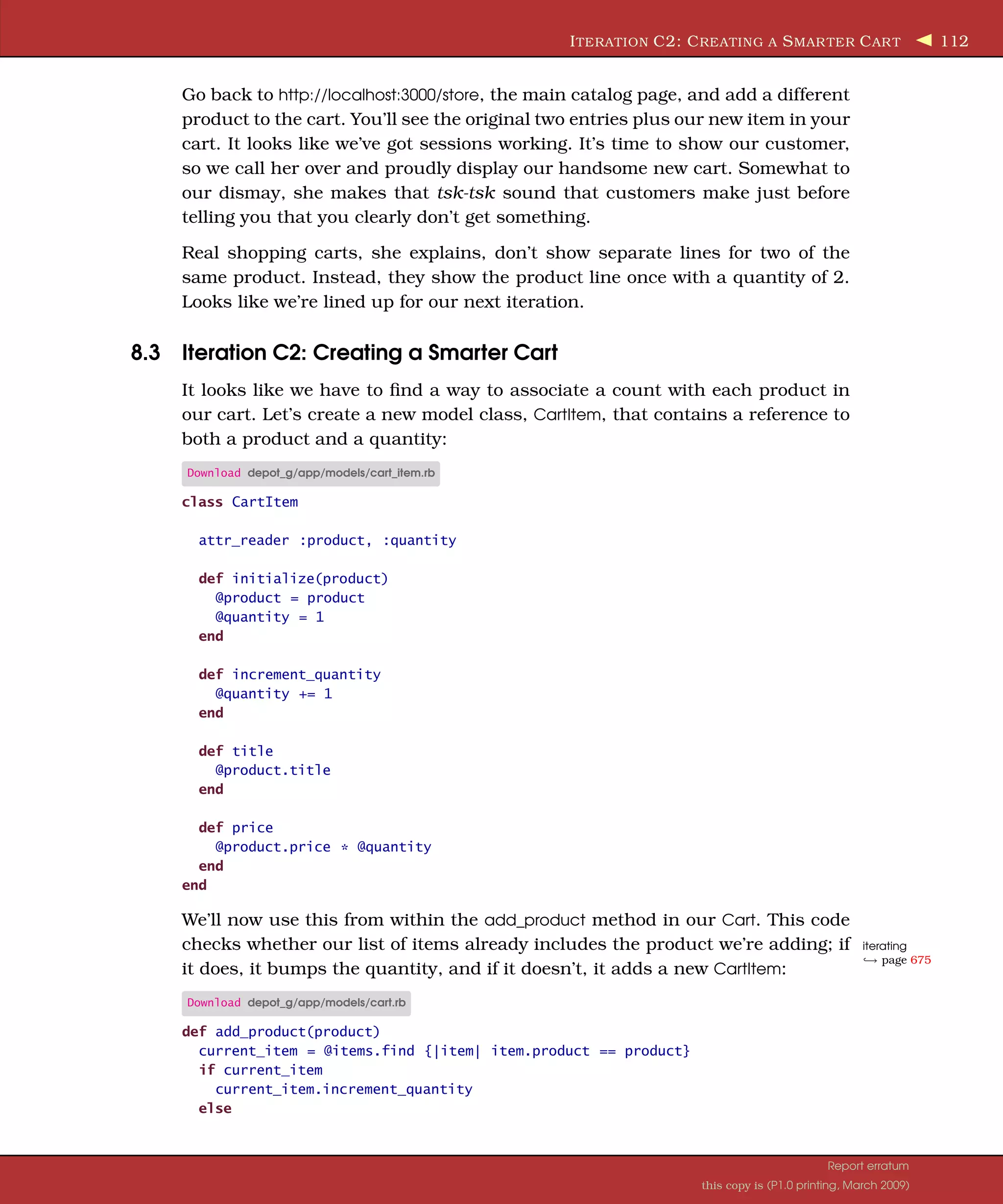

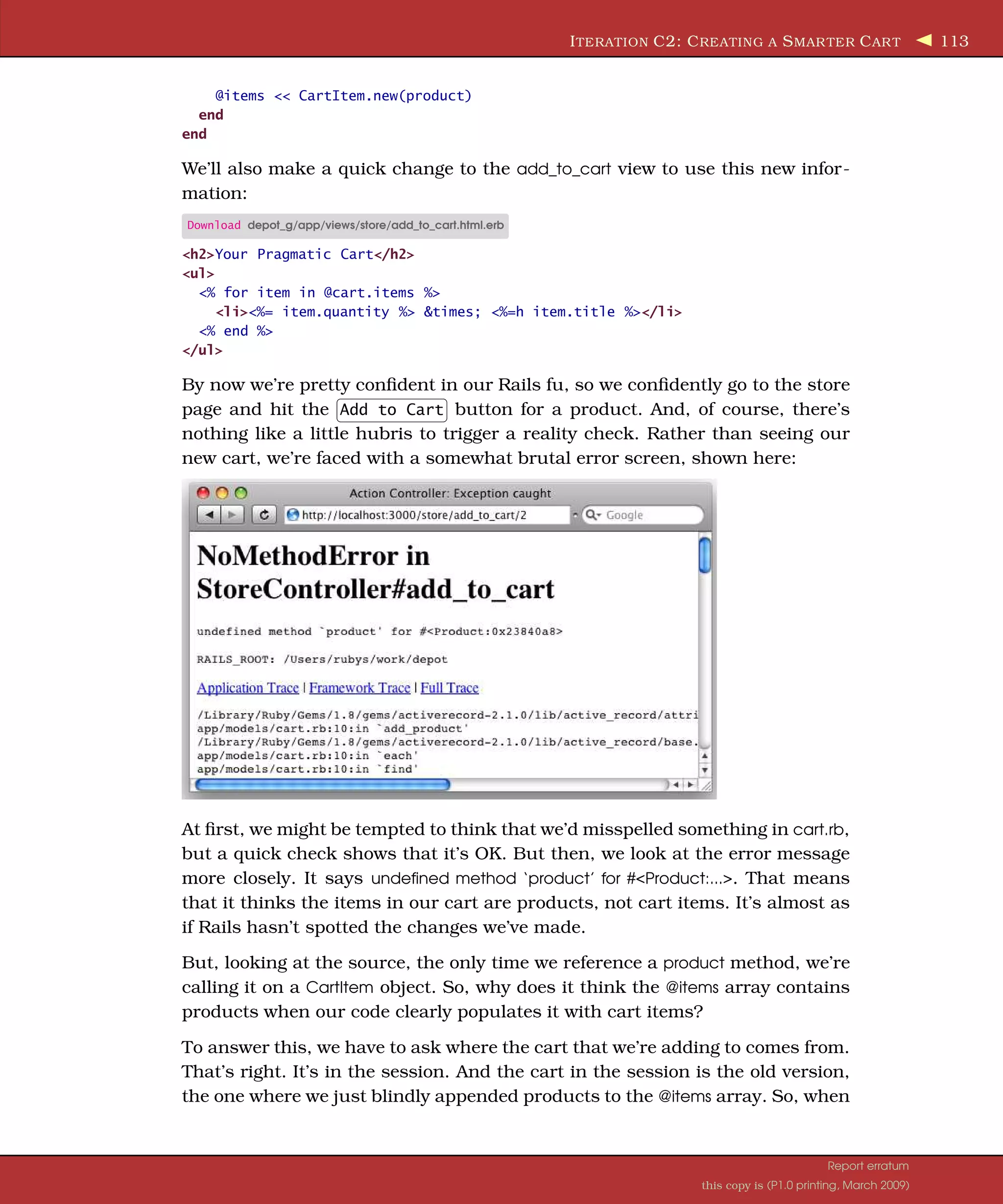

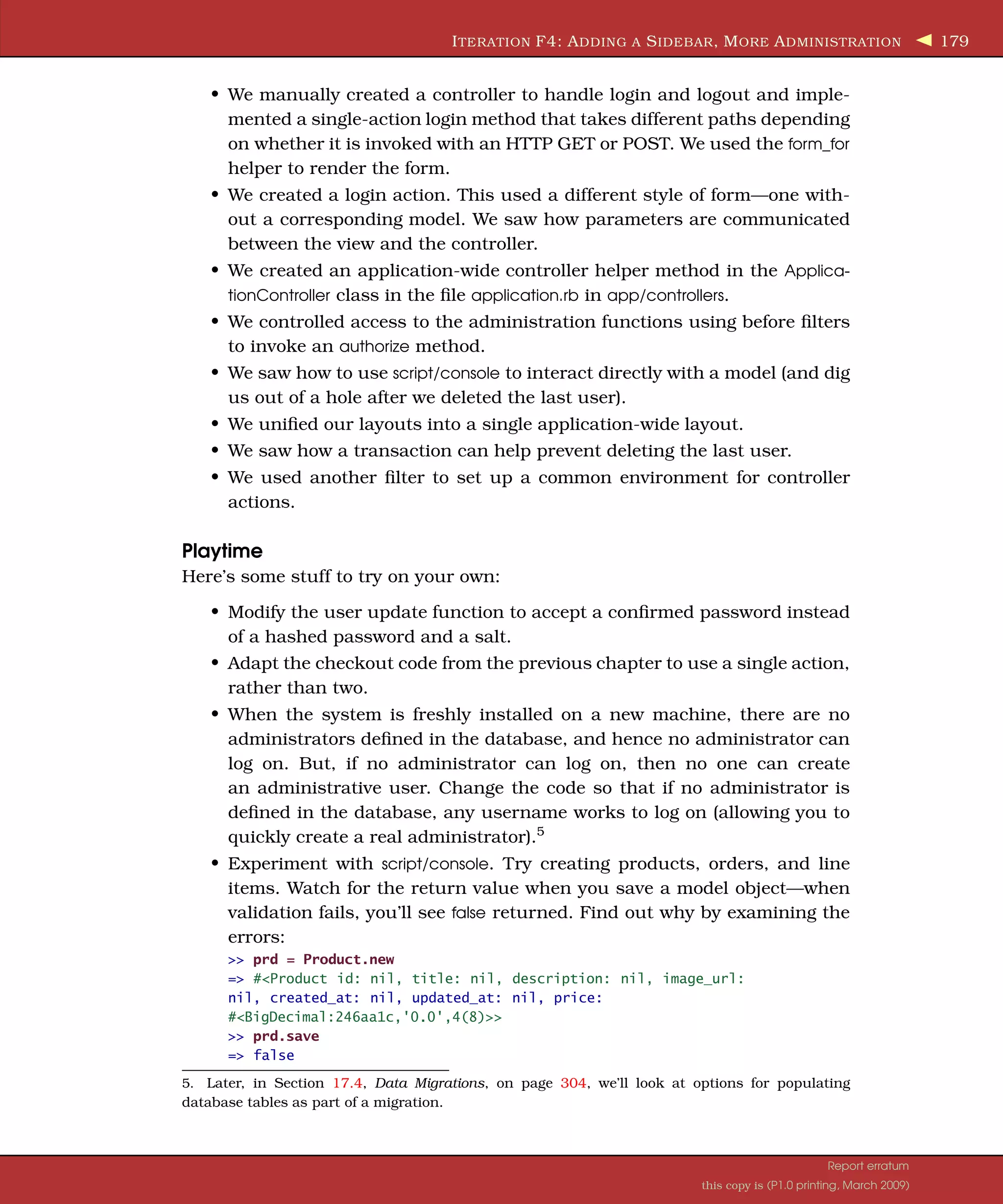

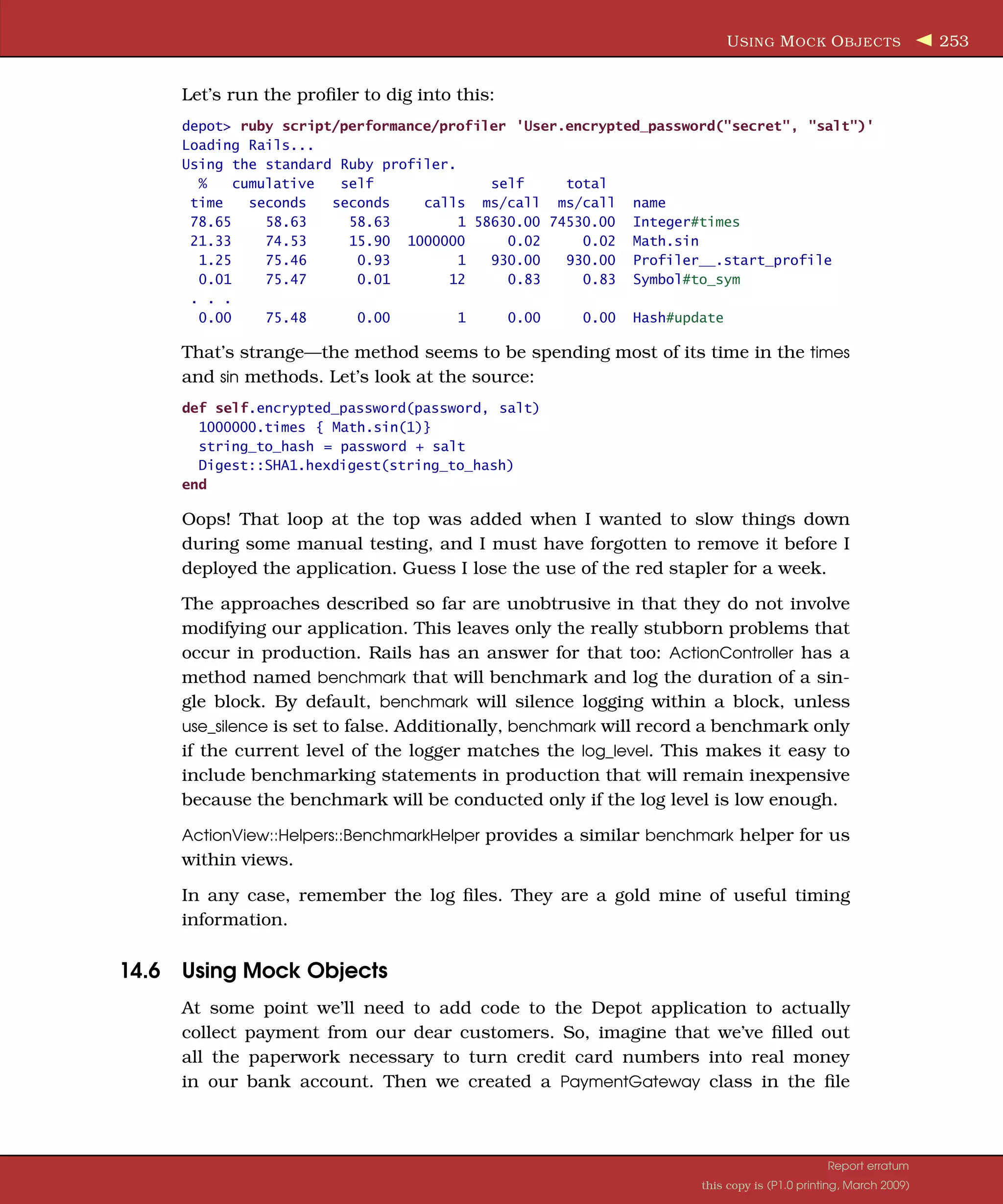

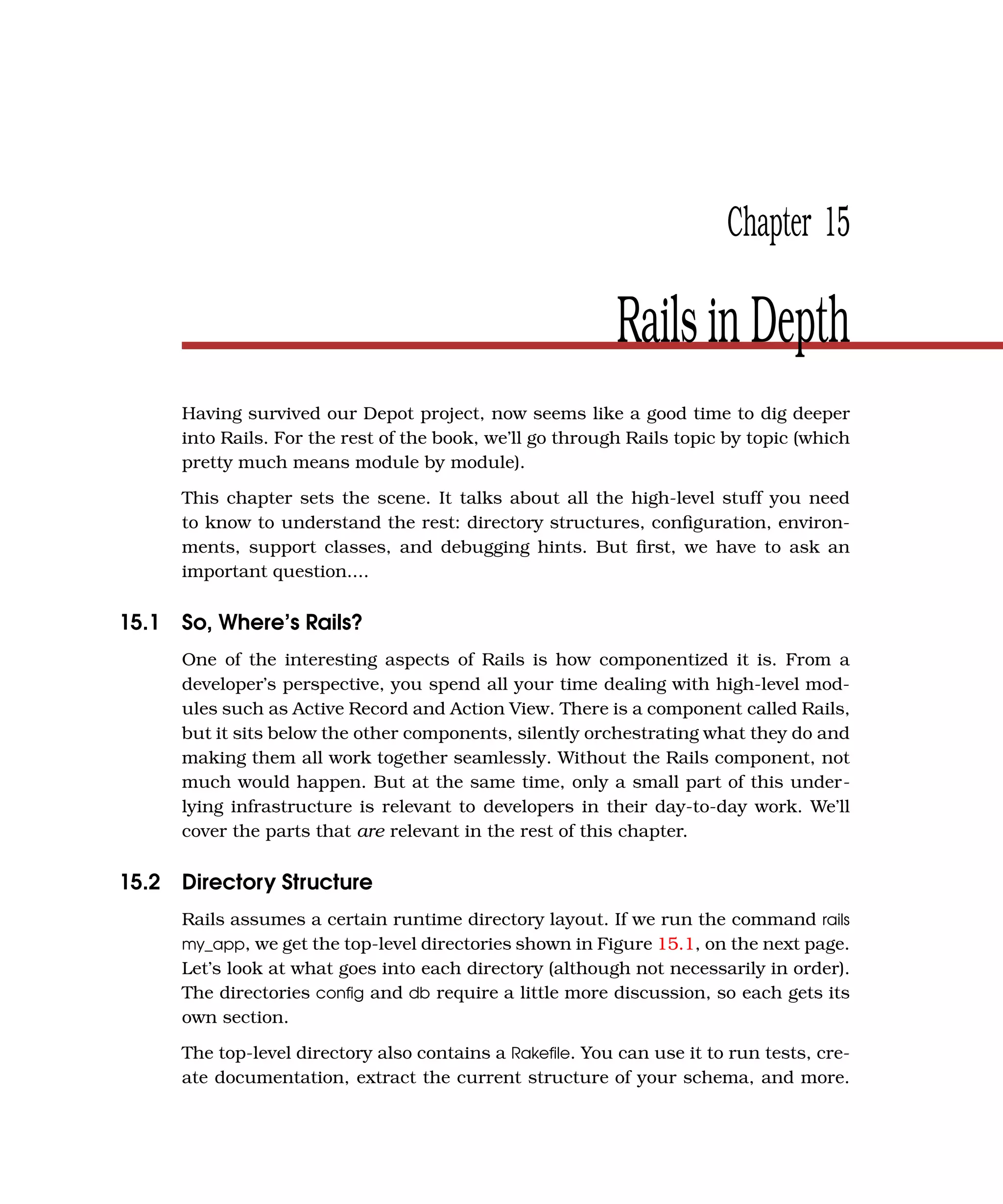

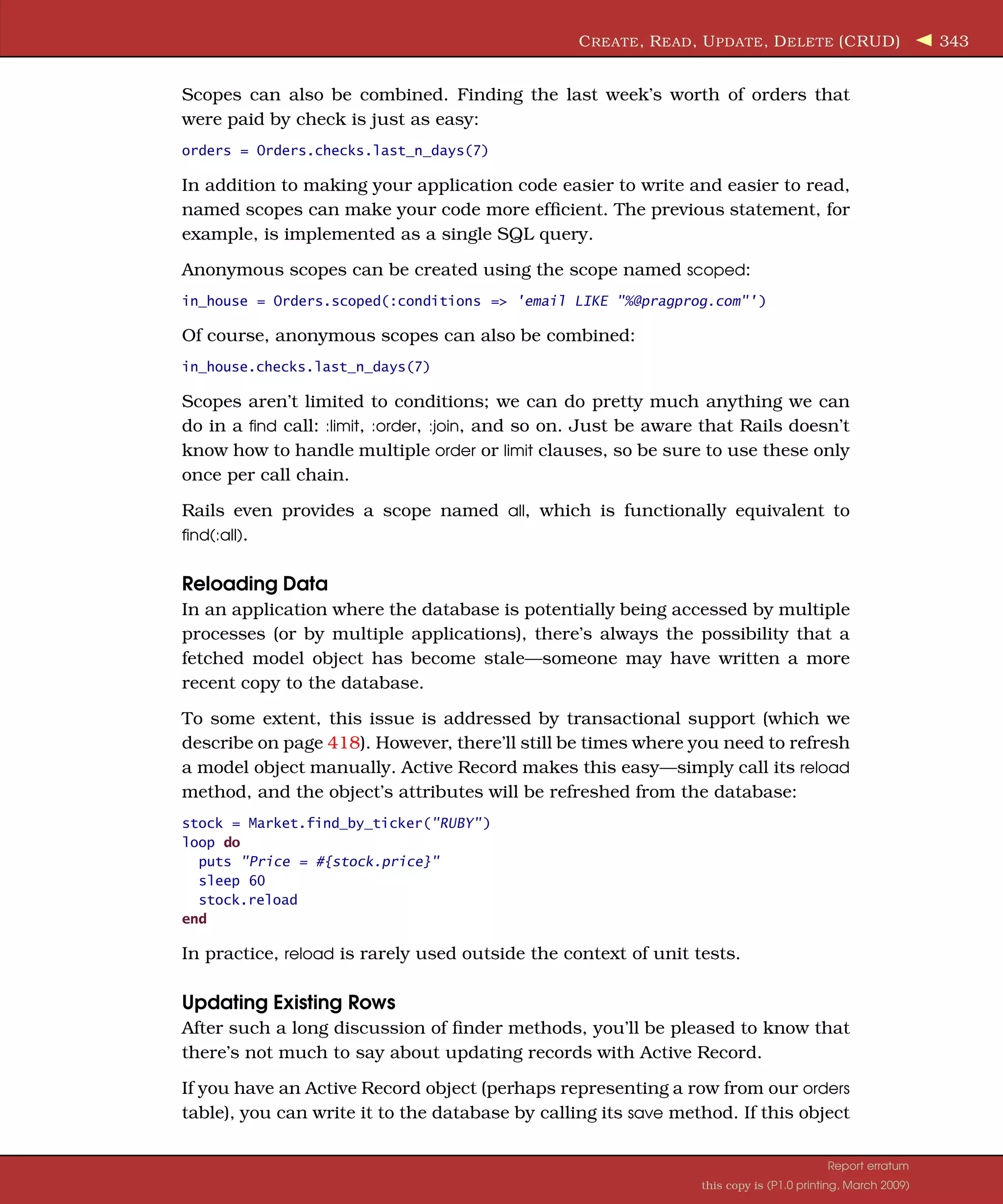

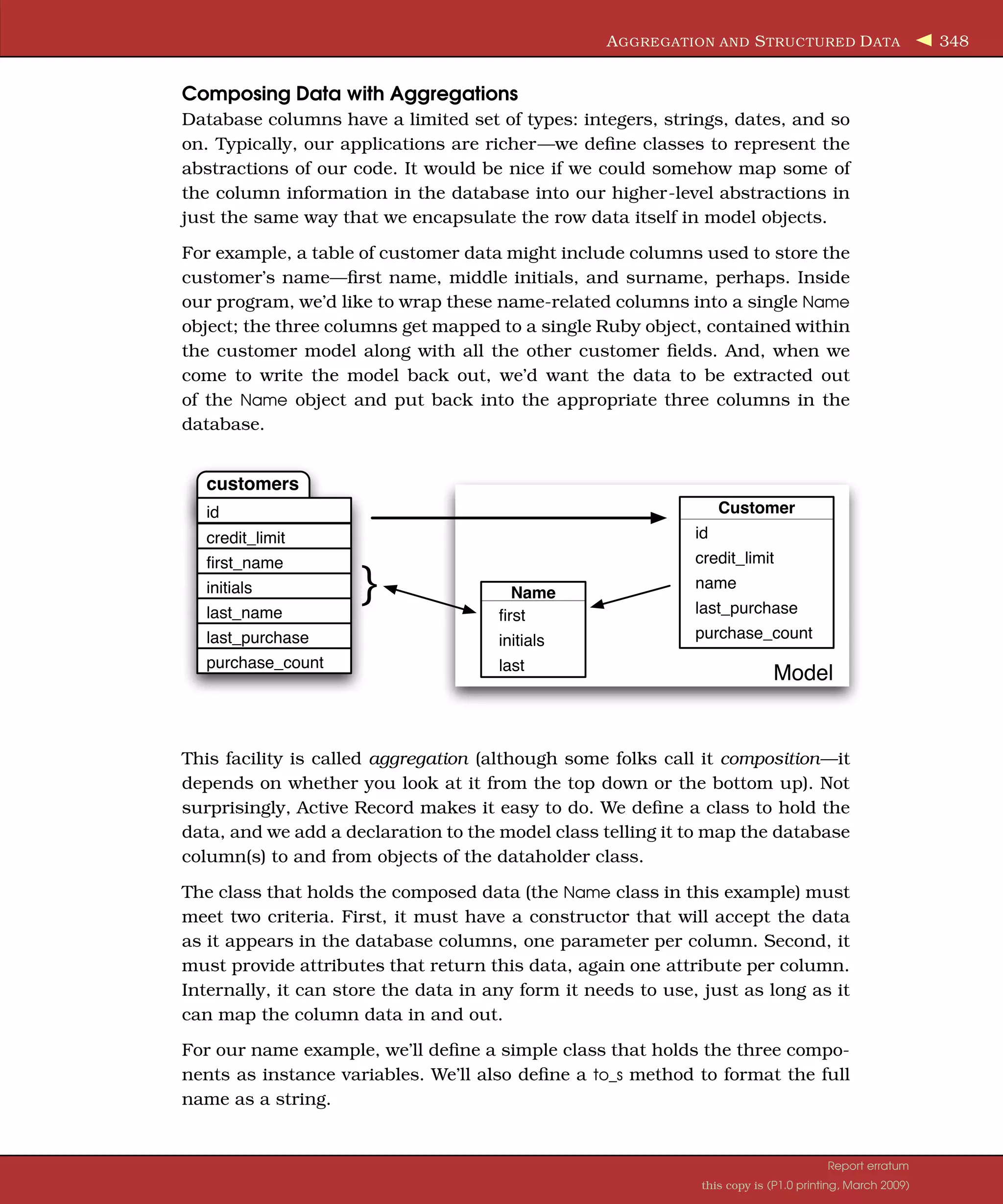

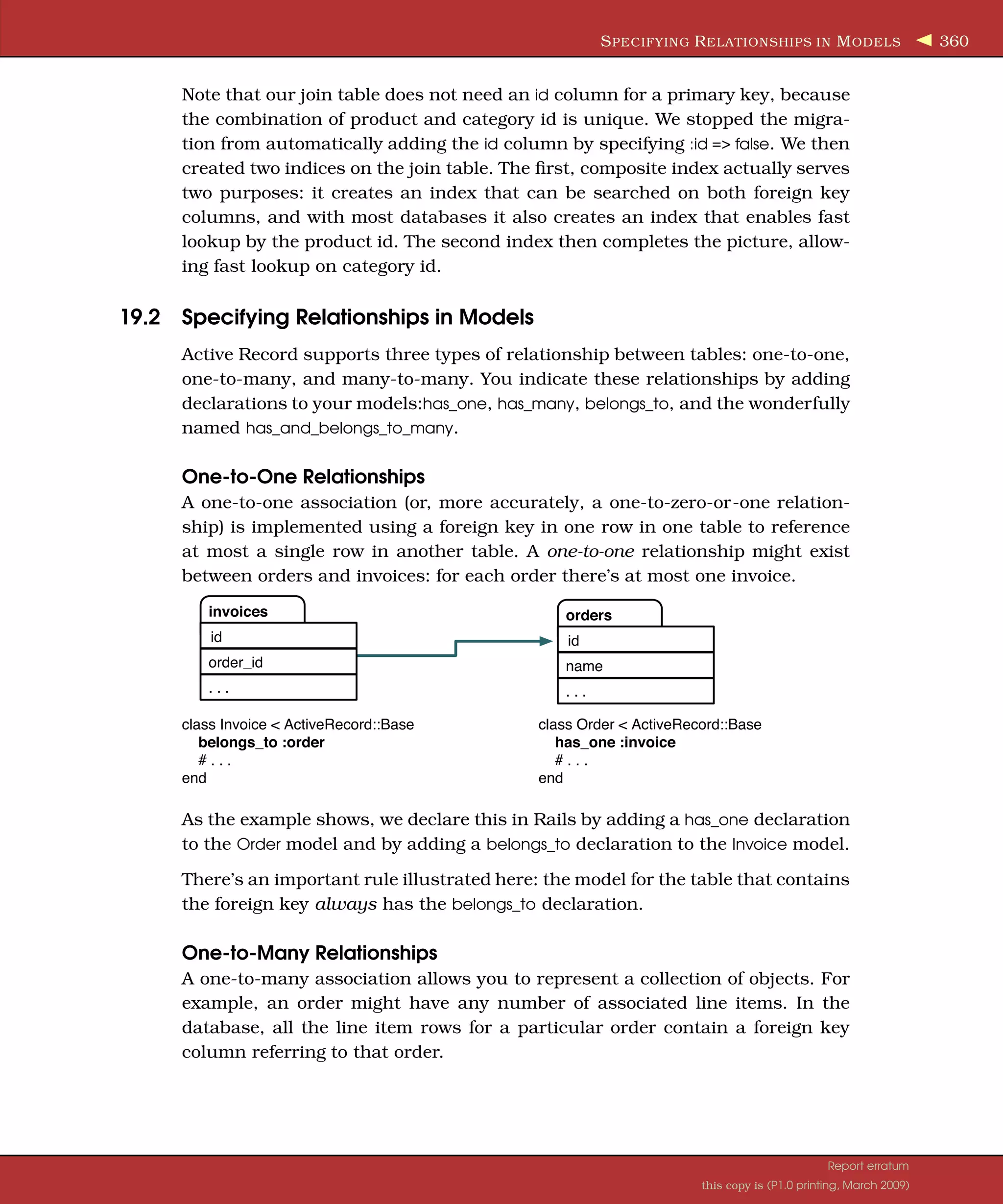

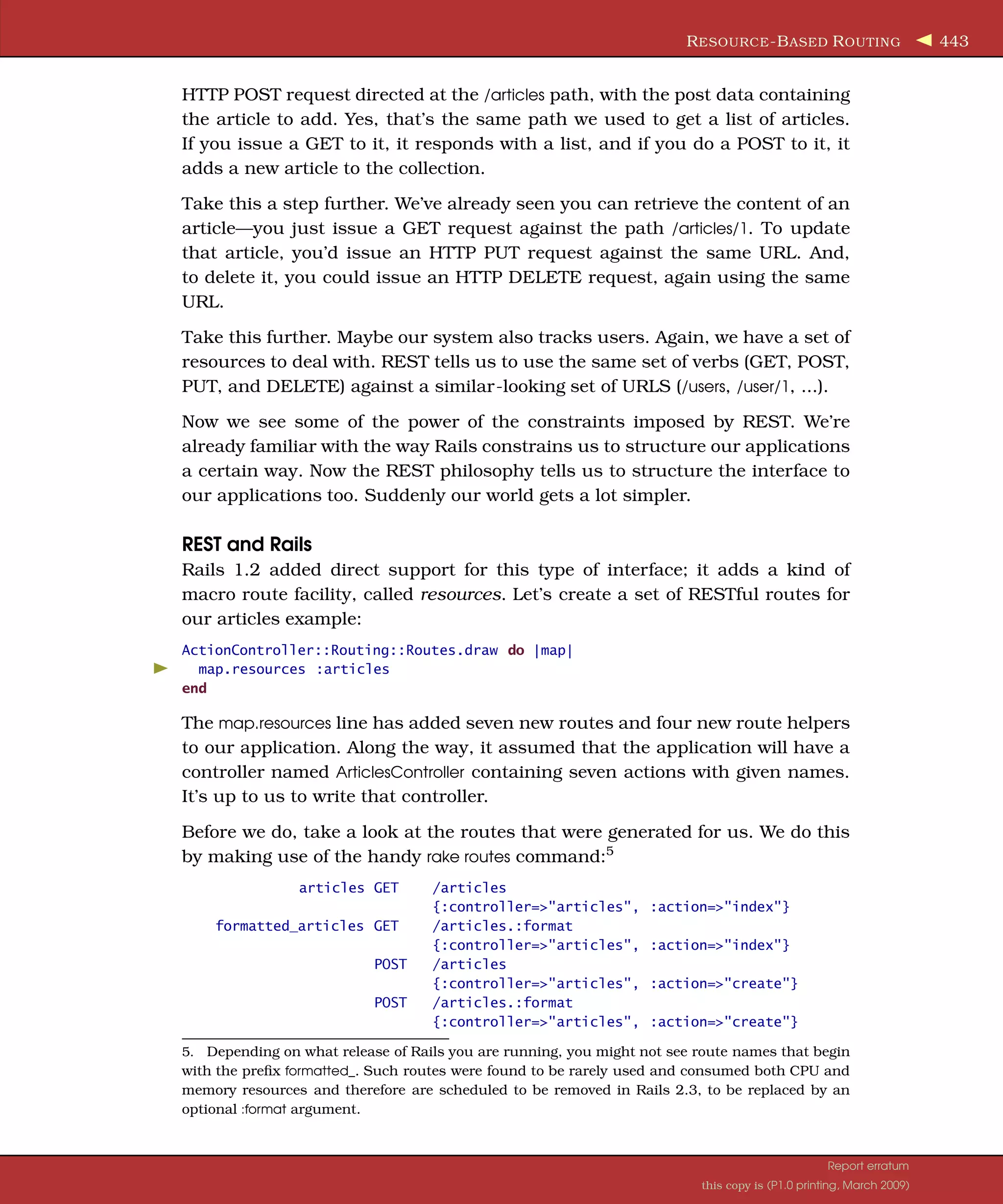

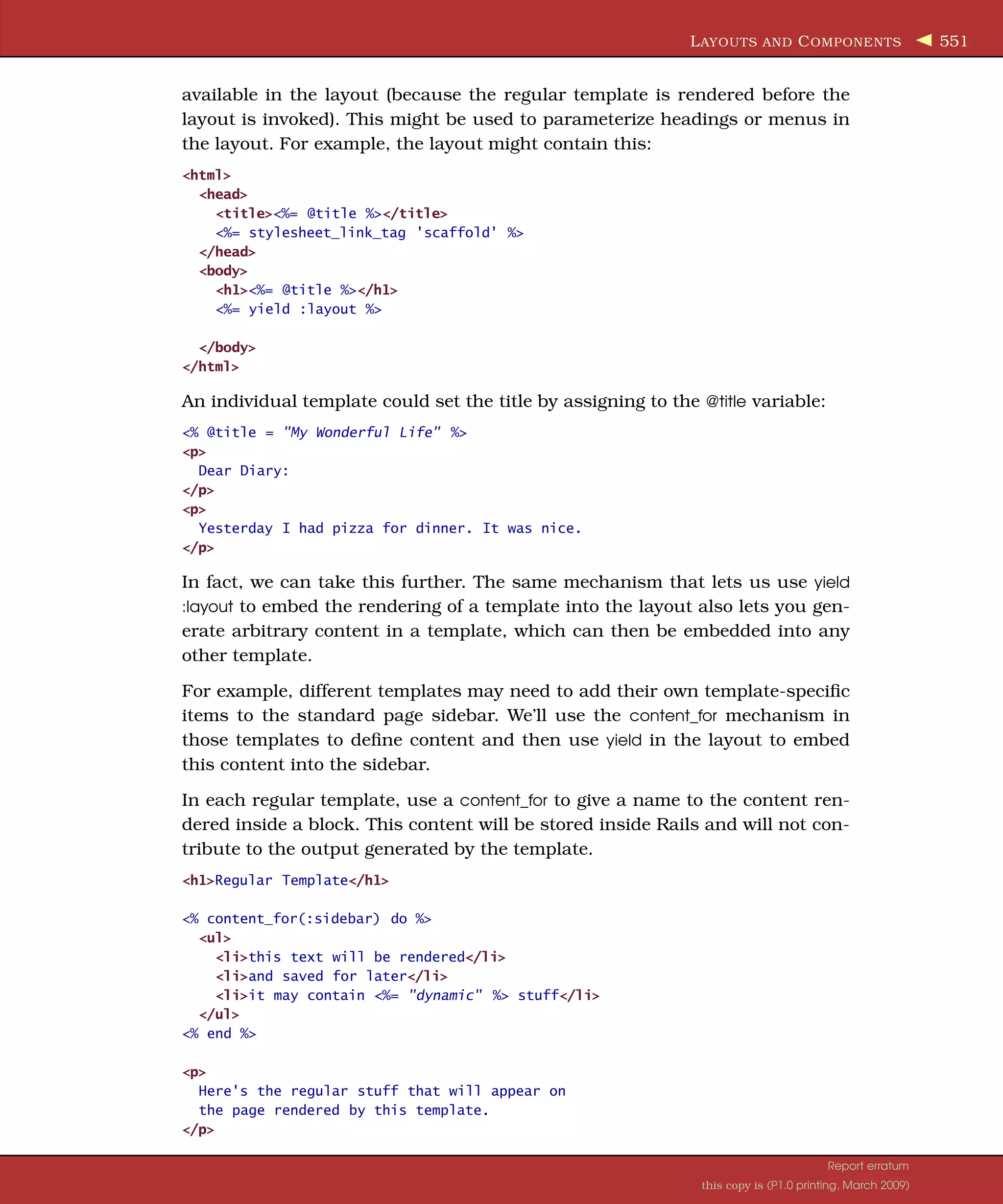

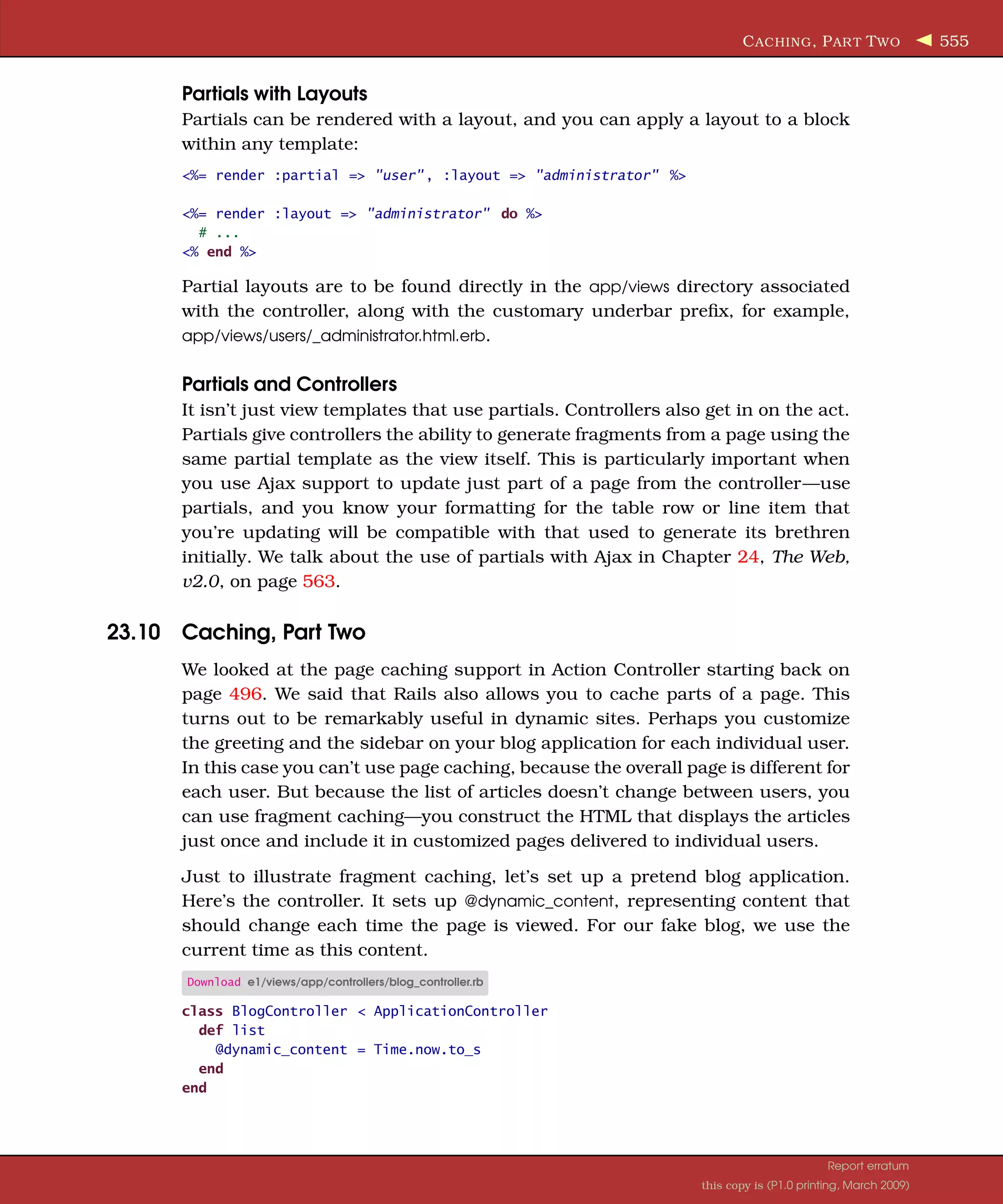

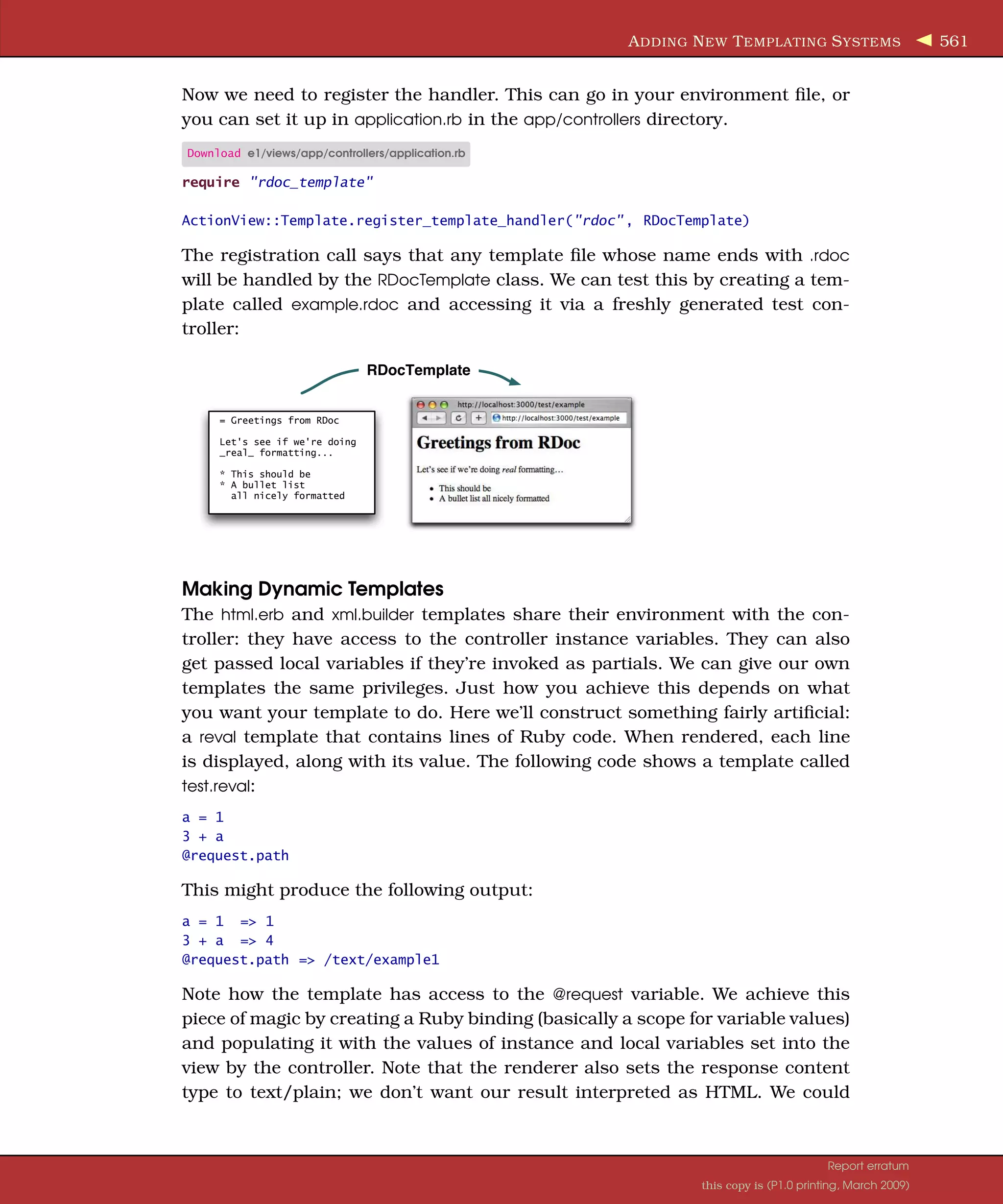

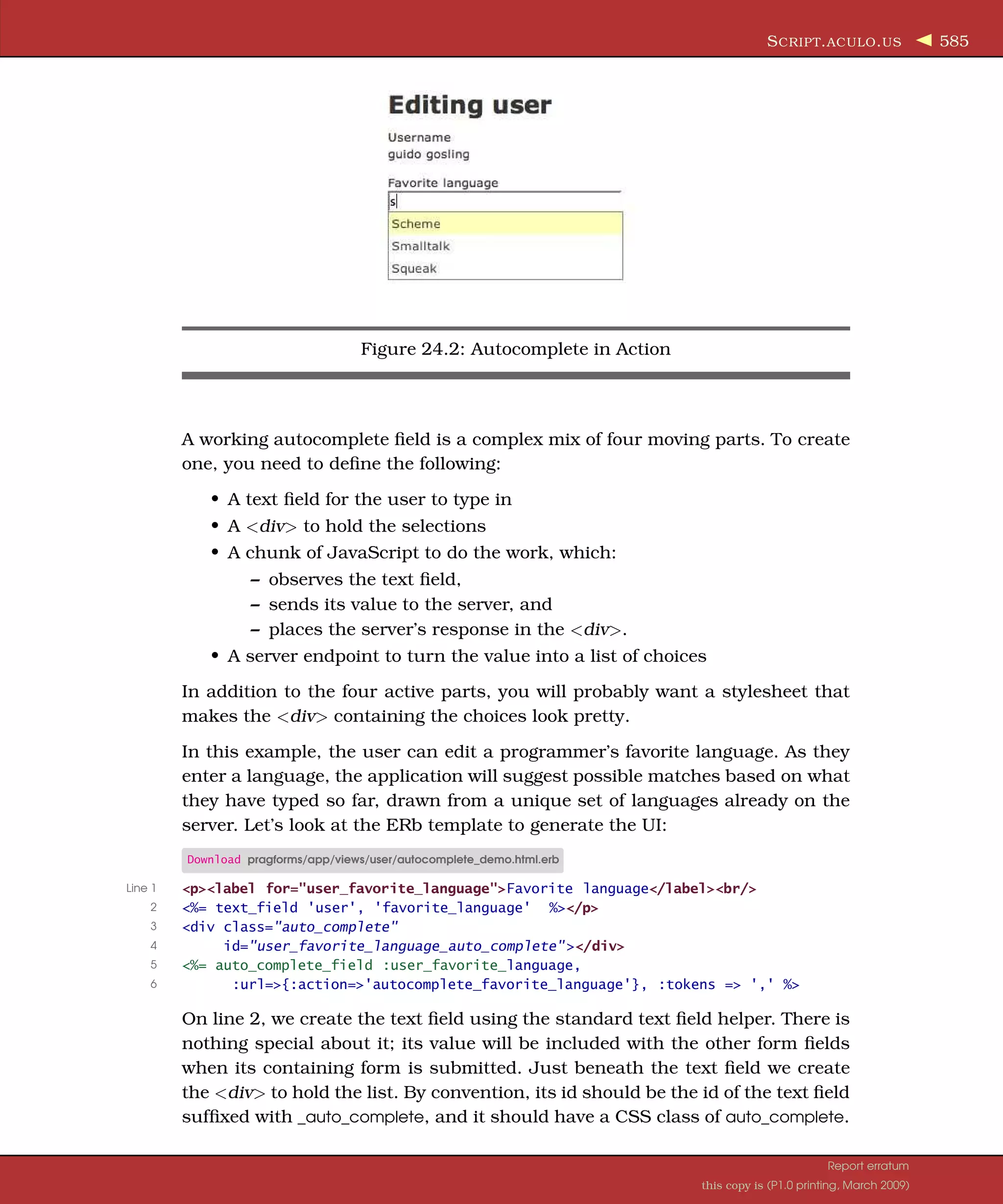

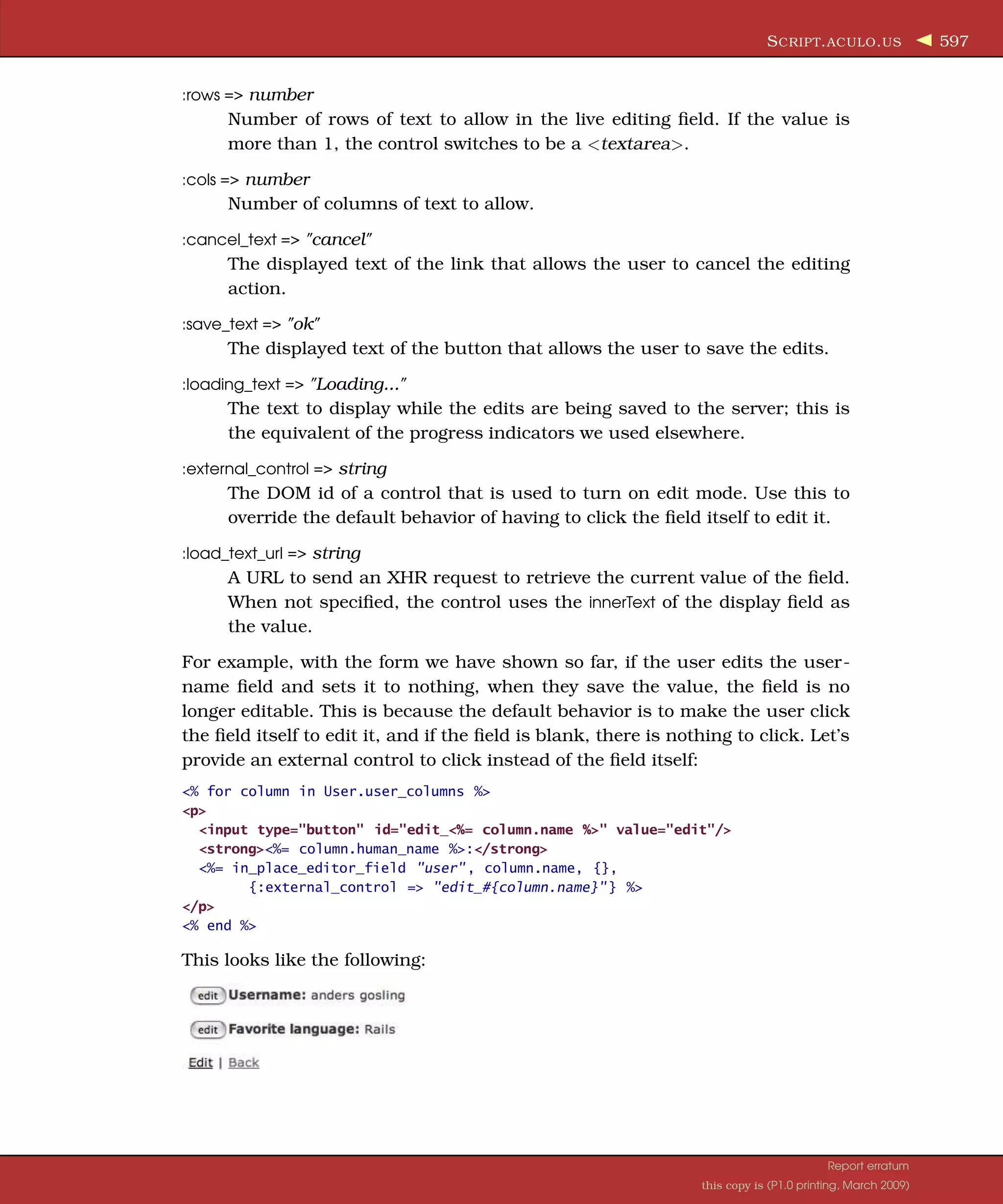

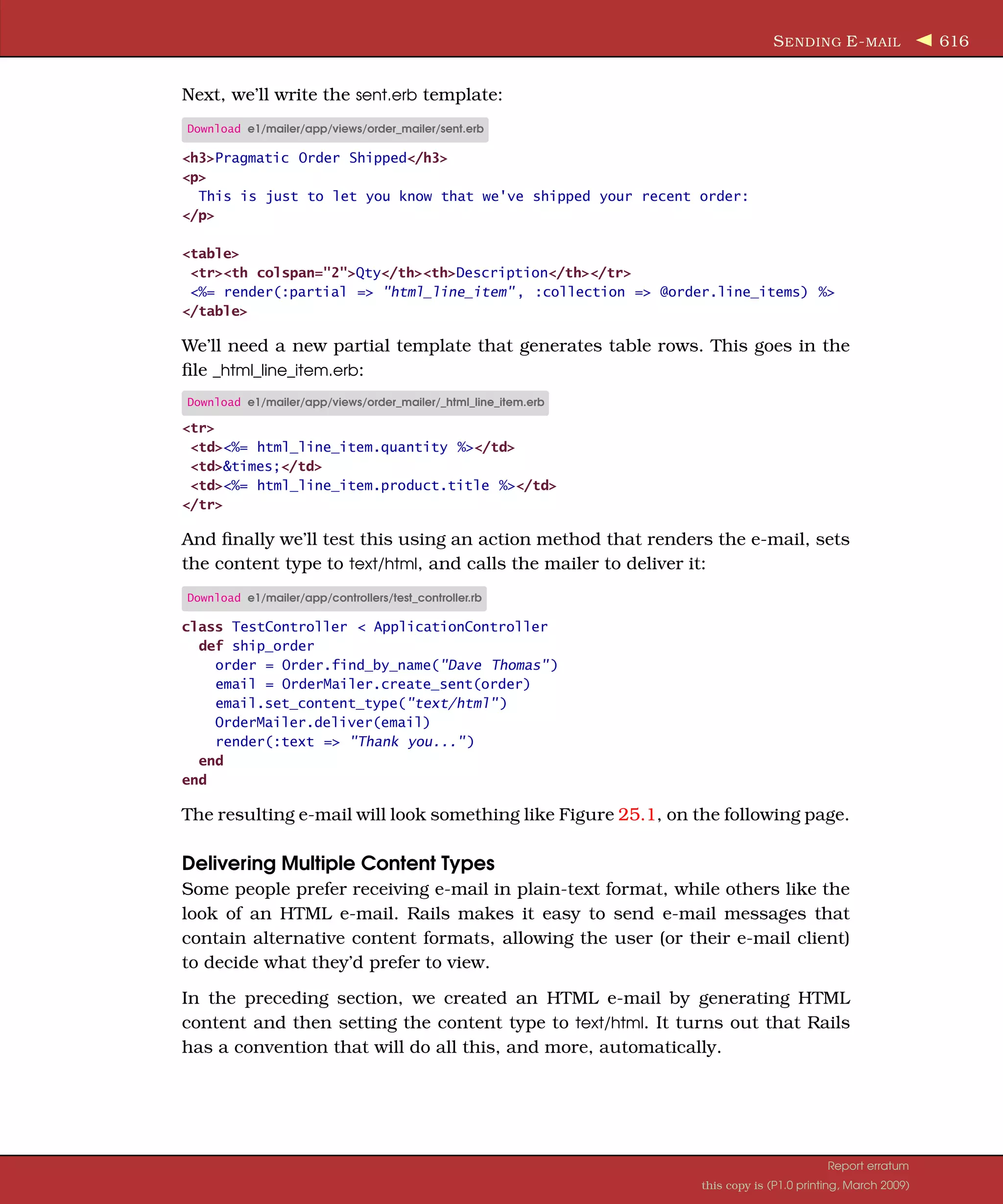

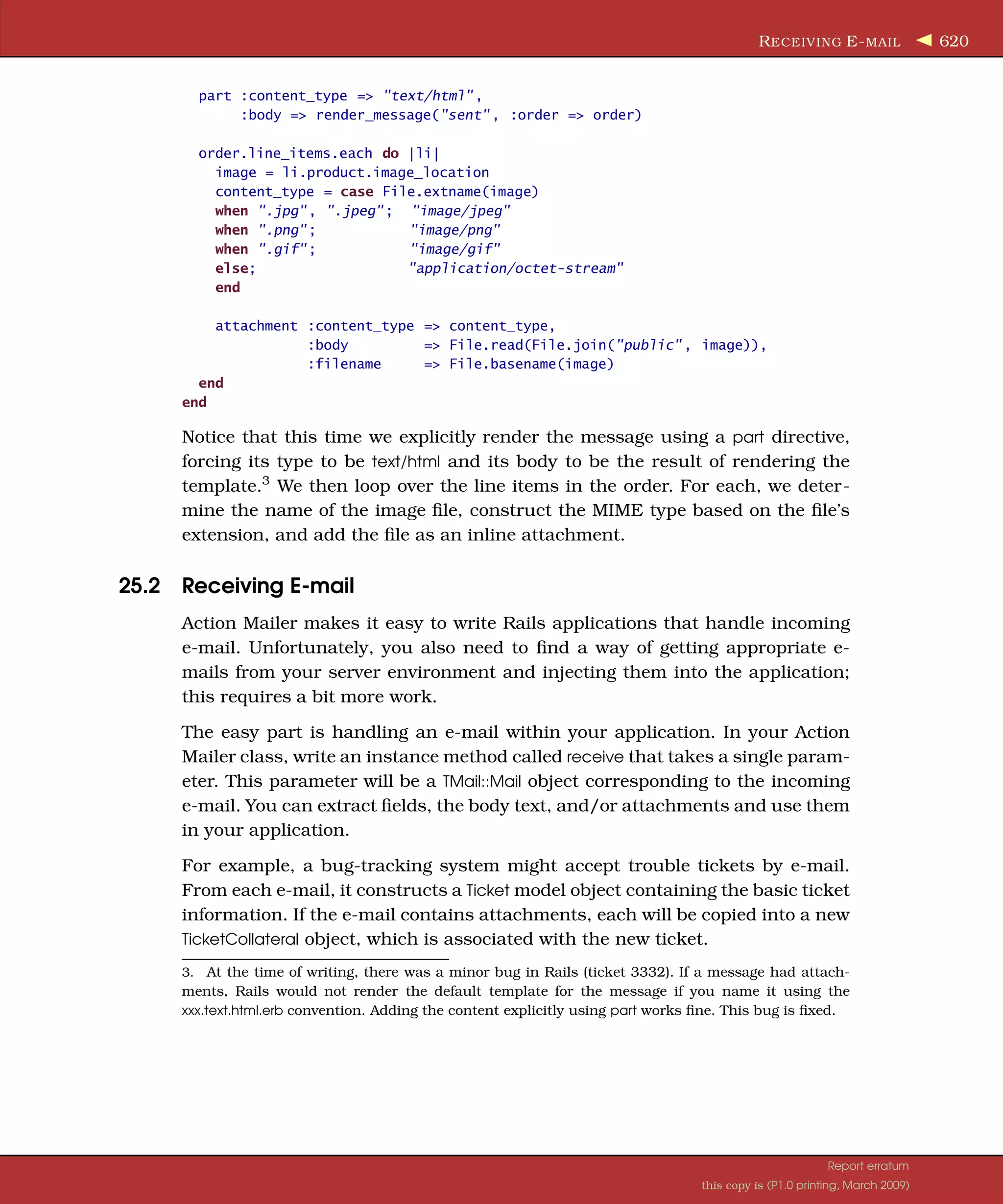

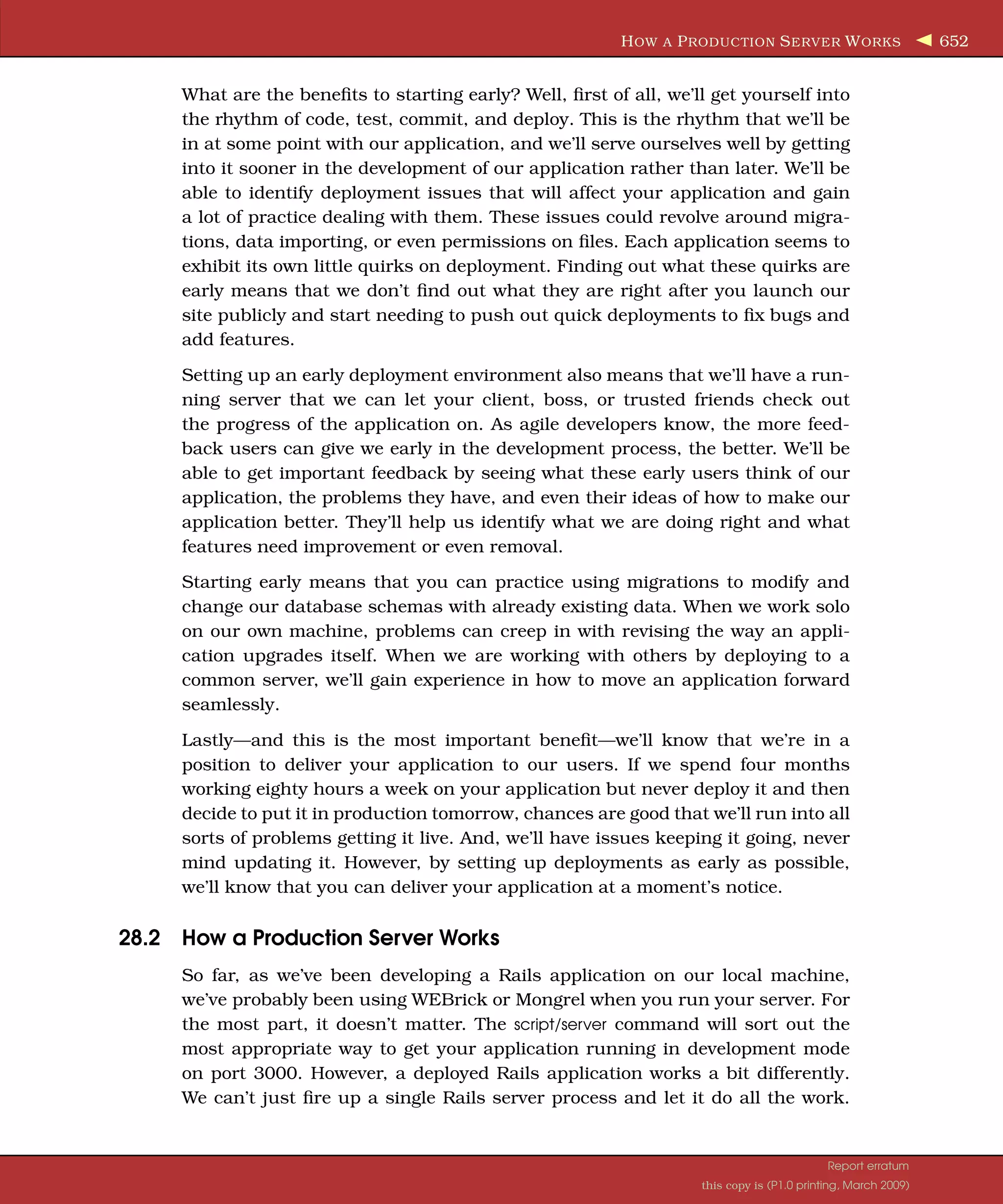

![I TERATION F4: A DDING A S IDEBAR , M ORE A DMINISTRATION 177 roll the transaction back, restoring the user we just deleted. To do this, we’ll use an Active Record hook method. We’ve already seen one of these: the validate hook is called by Active Record to validate an object’s state. It turns out that Active Record defines twenty or so hook methods, each called at a particular point in an object’s life cycle. We’ll use the after_destroy hook, which is called after the SQL delete is executed. If a method by this name is publicly visible, it will conveniently be called in the same transaction as the delete, so if it raises an exception, the transaction will be rolled back. The hook method looks like this: Download depot_q/app/models/user.rb def after_destroy if User.count.zero? raise "Can't delete last user" end end The key concept here is the use of an exception to indicate an error when delet- ing the user. This exception serves two purposes. First, because it is raised inside a transaction, it causes an automatic rollback. By raising the exception if the users table is empty after the deletion, we undo the delete and restore that last user. Second, the exception signals the error back to the controller, where we use a begin/end block to handle it and report the error to the user in the flash. If you want only to abort the transaction but not otherwise signal an exception, raise an ActiveRecord::Rollback exception instead, because this is the only exception that won’t be passed on by ActiveRecord::Base.transaction. Download depot_q/app/controllers/users_controller.rb def destroy @user = User.find(params[:id]) begin flash[:notice] = "User #{@user.name} deleted" @user.destroy rescue Exception => e flash[:notice] = e.message end respond_to do |format| format.html { redirect_to(users_url) } format.xml { head :ok } end In fact, this code still has a potential timing issue—it is still possible for two administrators each to delete the last two users if their timing is right. Fixing this would require more database wizardry than we have space for here. Report erratum this copy is (P1.0 printing, March 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pragmatic-agilewebdevelopmentwithrails-3rdedition-2009-091104222637-phpapp01/75/Pragmatic-Agile-Web-Development-With-Rails-3rd-Edition-2009-177-2048.jpg)