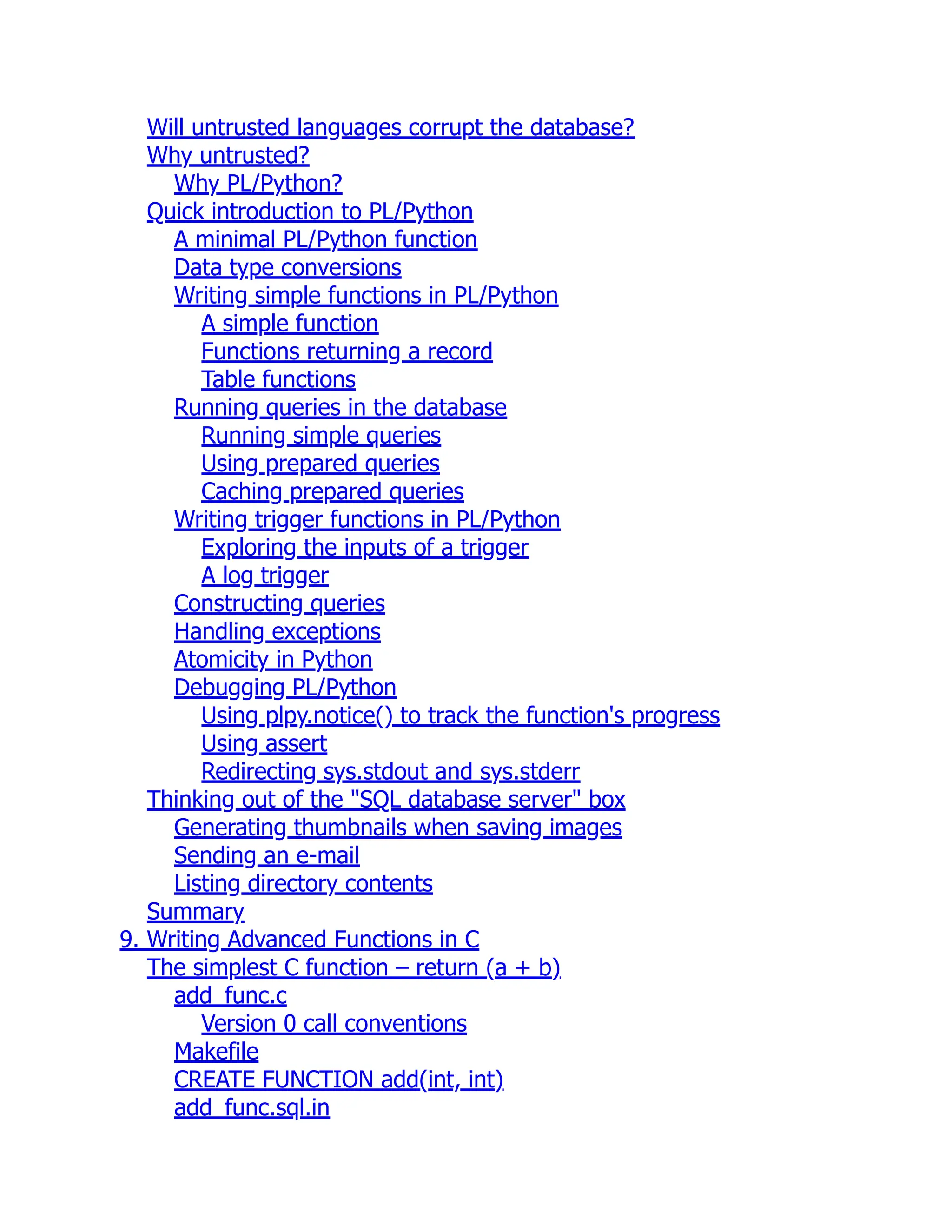

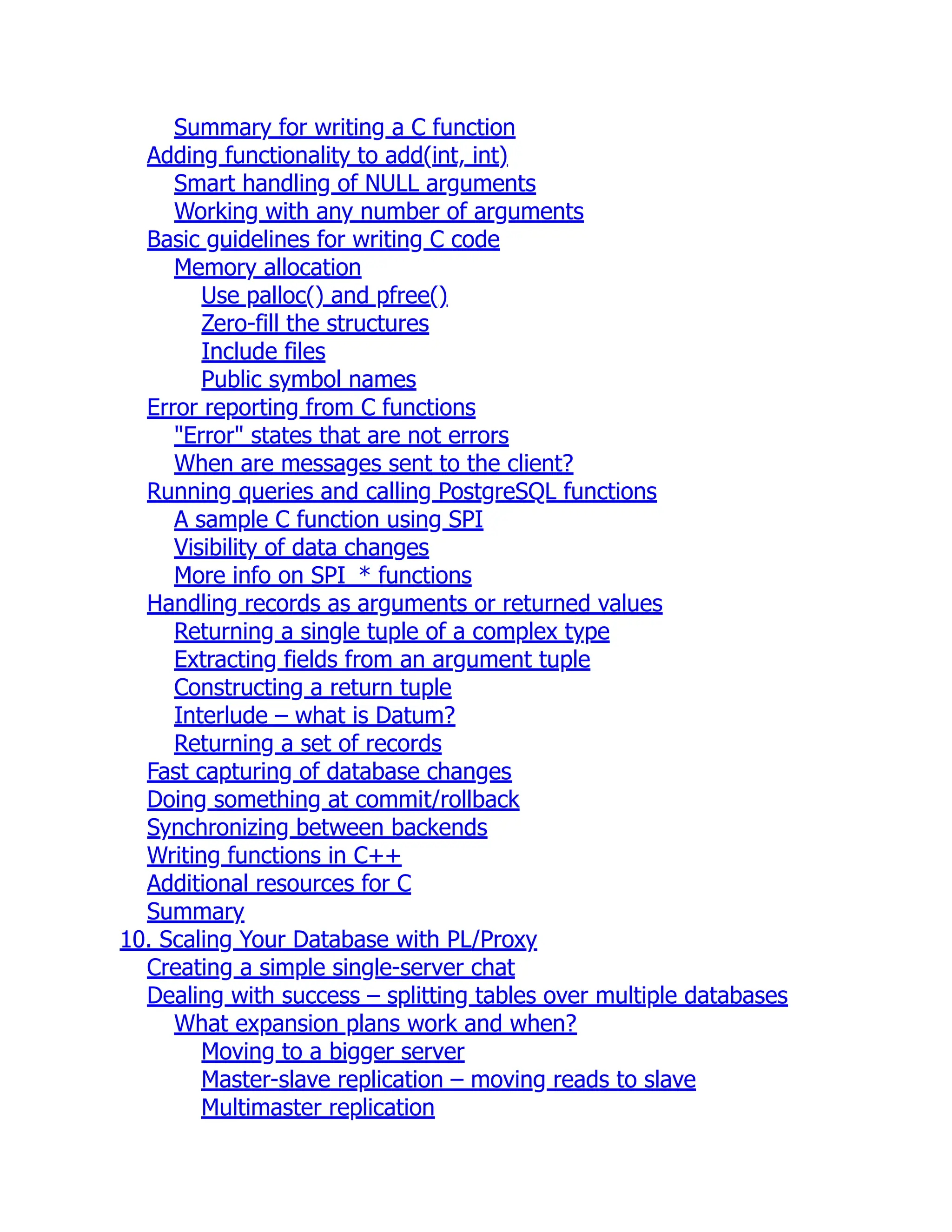

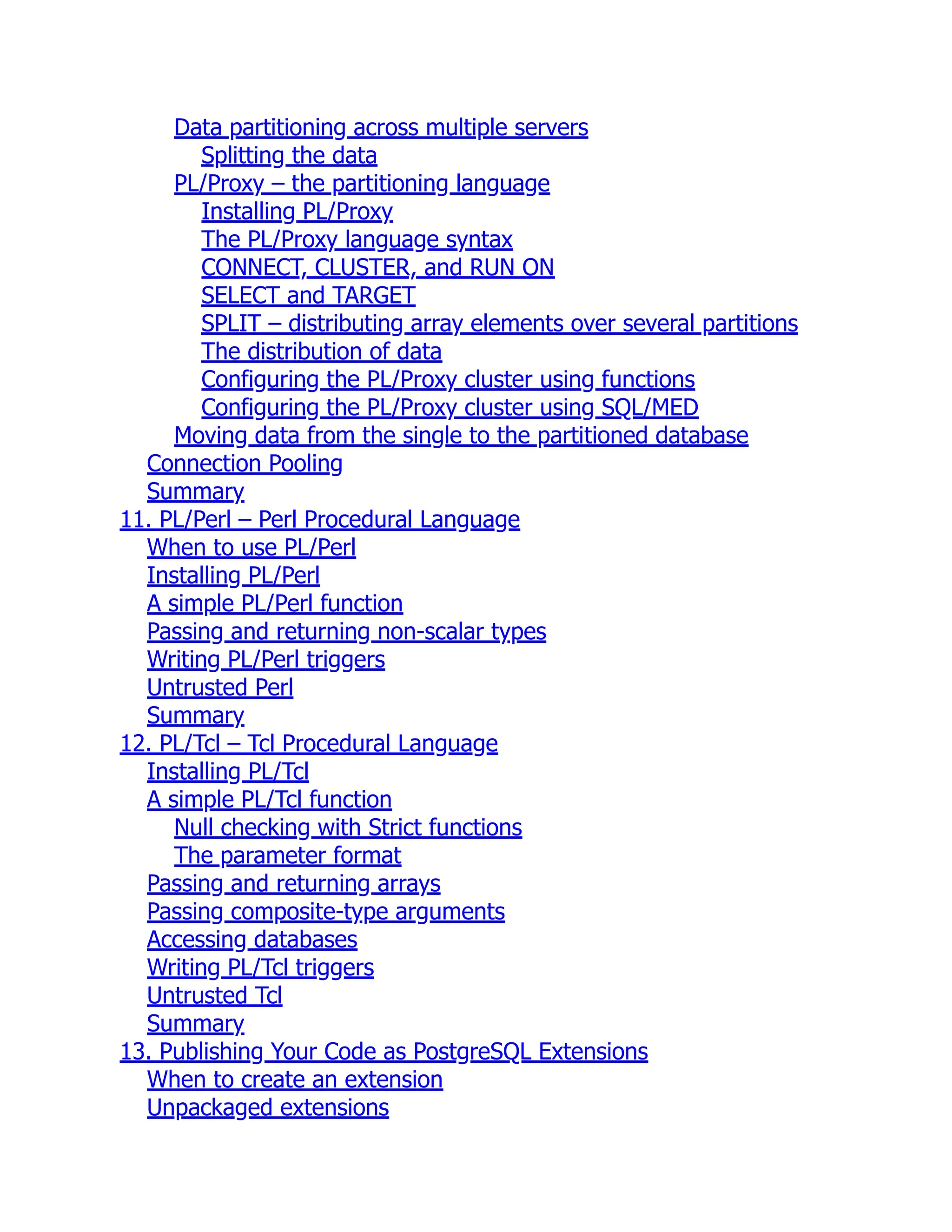

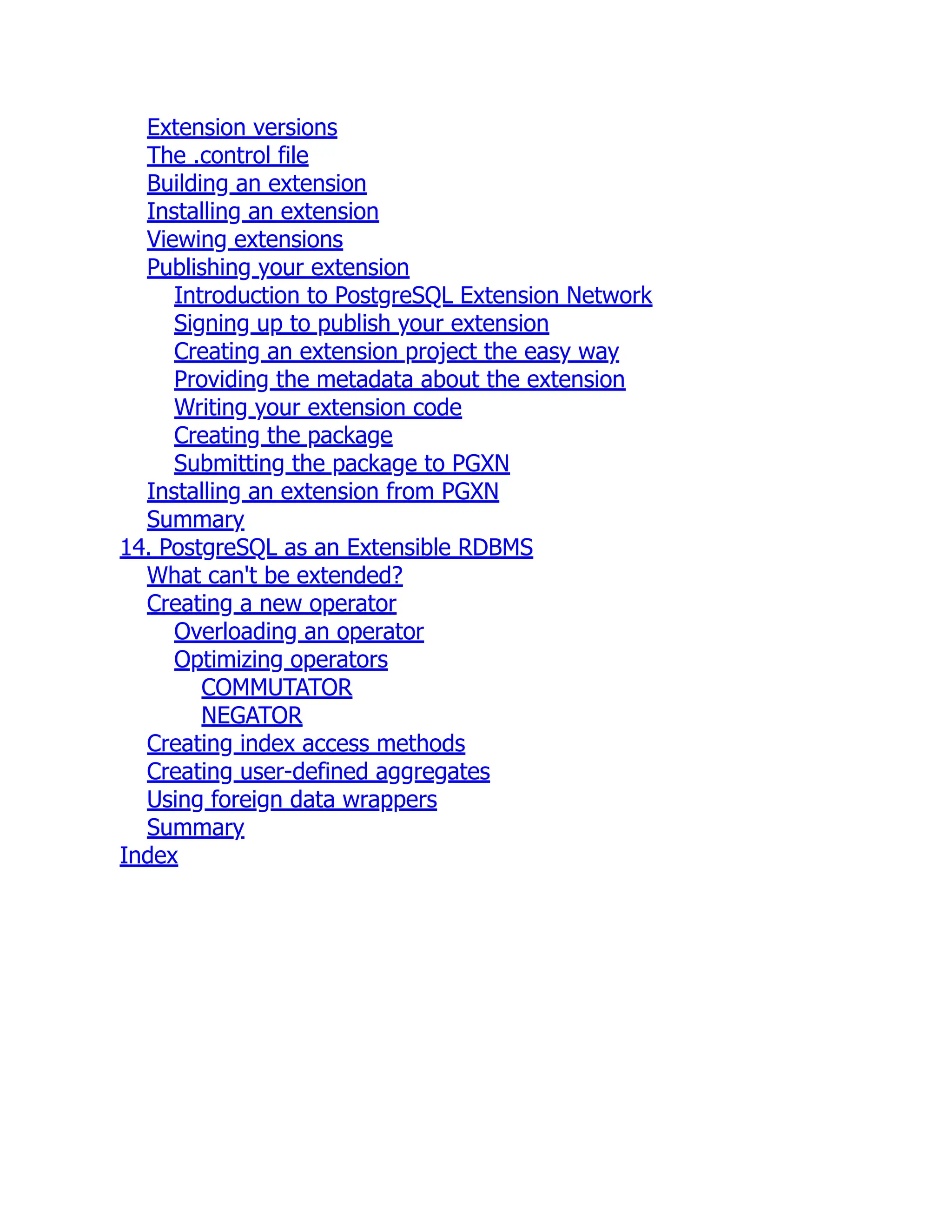

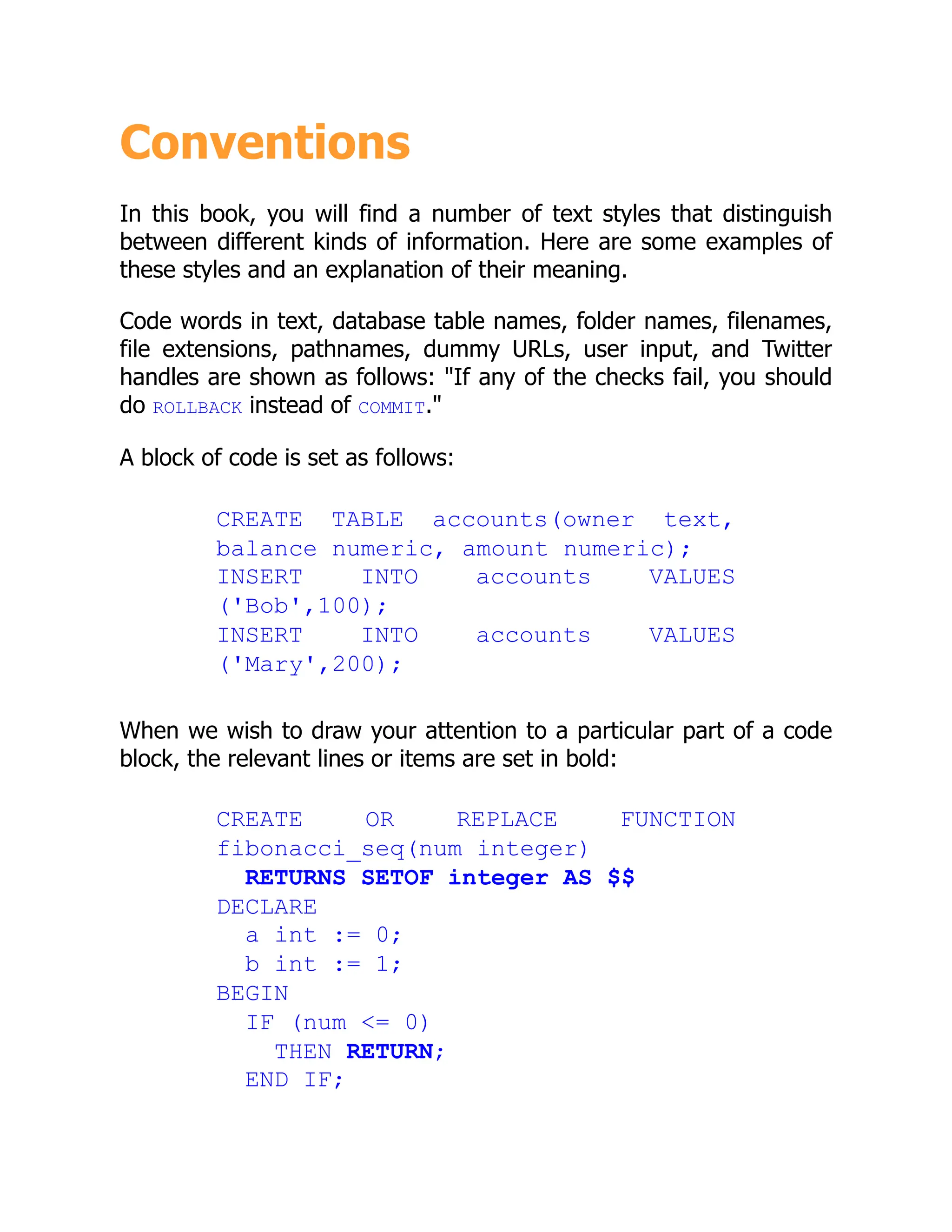

The document provides an extensive overview of the 'PostgreSQL Server Programming, Second Edition,' covering a variety of topics from PostgreSQL fundamentals to advanced programming techniques in PL/pgSQL, PL/Python, PL/Perl, and PL/Tcl. It includes detailed explanations on creating functions, triggers, and extensions, as well as best practices for database design and performance optimization. Additionally, the book includes authors' backgrounds, acknowledgments, and information on the PostgreSQL community and available resources.