Everyone knows that Weird Al lampooned computers in a famous parody song (It’s All About the Pentiums). But if you want more hardcore (including more hardcore language, so if you are offended by rap music-style explicit lyrics, maybe don’t look this up), you probably want “Kill Dash 9” by Monzy. There’s a line in that song about “You thought the seven-layer model referred to a burrito.” In fact, it refers to how networking applications operate, and it is so ingrained that you don’t even hear about it much these days. But as [Codemia] points out, QUIC aims to disrupt the model, and for good reason.

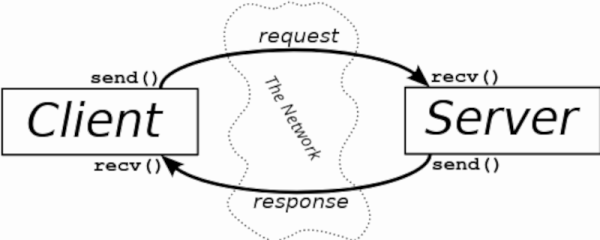

Historically, your application (at layer 7) interacts with the network through other layers like the presentation layer and session layer. At layer 4, though, there is the transport layer where two names come into play: TCP and UDP. Generally, UDP is useful where you want to send data and you don’t expect the system to do much. Data might show up at its destination. Or not. Or it might show up multiple times. It might show up in the wrong order. TCP solves all that, but you have little control over how it does that.

When things are congested, there are different strategies TCP can use, but changing them can be difficult. That’s where QUIC comes in. It is like a user-space TCP layer built over a UDP transport. There are a lot of advantages to that, and if you want to know more, or even just want a good overview of network congestion control mitigations, check the post out.

If you want to know more about congestion control, catch a wave.