Although something that’s taken for granted these days, the ability to perform floating-point operations in hardware was, for the longest time, something reserved for people with big wallets. This began to change around the time that Intel released the 8087 FPU coprocessor in 1980, featuring hardware support for floating-point arithmetic at a blistering 50 KFLOPS. Notably, the 8087 uses a stack-based architecture, a major departure from existing FPUs. Recently [Ken Shirriff] took a literal closer look at this stack circuitry to see what it looks like and how it works.

Nearly half of the 8087’s die is taken up by the microcode frontend and bus controller, with a block containing constants like π alongside the FP calculation-processing datapath section taking up much of the rest. Nestled along the side are the eight registers and the stack controller. At 80 bits per FP number, the required registers and related were pretty sizeable for the era, especially when you consider that the roughly 60,000 transistors in the 8087 were paired alongside the 29,000 transistors in the 16-bit 8086.

Each of the 8087’s registers is selected by the decoded instructions via a lot of wiring that can still be fairly easily traced despite the FPU’s die being larger than the CPU it accompanied. As for the unique stack-based register approach, this turned out to be mostly a hindrance, and the reason why the x87 FP instructions in the x86 ISA are still quite maligned today. Yet with careful use, providing a big boost over traditional code, this made it a success by that benchmark, even if MMX, SSE, and others reverted to a stackless design.

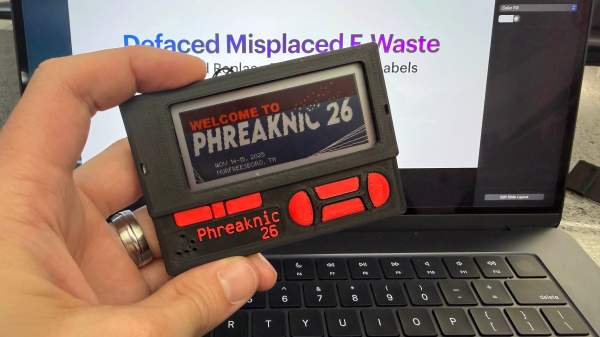

Another hacker assisting with the badge project, [Mog], noticed that the spacing of the programming pads on the PCB was very close to the spacing of a DB9/DE9 cable. This gave way to a very clever hack for programming the badges: putting pogo pins into a female connector. The other end of the cable was connected to a TI CC Debugger which was used to program the firmware on the displays. But along the way, even this part of the project got an upgrade with moving to an ESP32 for flashing firmware, allowing for firmware updates without a host computer.

Another hacker assisting with the badge project, [Mog], noticed that the spacing of the programming pads on the PCB was very close to the spacing of a DB9/DE9 cable. This gave way to a very clever hack for programming the badges: putting pogo pins into a female connector. The other end of the cable was connected to a TI CC Debugger which was used to program the firmware on the displays. But along the way, even this part of the project got an upgrade with moving to an ESP32 for flashing firmware, allowing for firmware updates without a host computer.